Jair Bolsonaro – the candidate who has called for civil war, cheered violence against women, trashed the free press, threatened to beat up homosexuals, and proudly proclaimed disrespect for the democratic process – will be the next president of Brazil. Having secured a whopping 46% of the vote in last week’s election – just shy of an outright majority – his only hurdle is the run-off election against the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate, Fernando Haddad, on October 28.

Haddad, for his part, looks hopeless. On Monday, his own campaign event turned against him, as a planned endorsement from the Democratic Labour Party candidate Ciro Gomes spun into a diatribe about Haddad’s failings. “You’re going to lose the election, and it’s your fault,” Gomes shouted.

Bolsonaro’s spectacular rise raises key questions about the appeal of authoritarianism – in Brazil and around the world. Who constitutes Bolsonaro’s base? Why are they turning toward such violence and bigotry? And what can it tell us about new populist movements emerging in advanced democracies today?

To make sense of these questions, I revisited the data from the World Values Survey (WVS), collected in over 60 countries between 2010 and 2014. Focusing on the sample from Brazil, I examined the relationship between respondents’ self-placement on a left-right spectrum — ranging from 1 to 10 — and their support for democracy.

The main finding? It is moderates, not extremists, who are most excited about authoritarianism in Brazil.

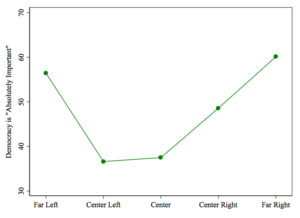

I began my analysis by looking at general attitudes toward democracy. The survey asks: “How important is it for you to live in a country that is governed democratically?”

Plotted against the Left-Right spectrum, the responses form a striking V-shape. People who identify at the extremes of the political spectrum are far more likely to value democracy than those who identify at the centre. While 56.4% of the far-Left and 60% of the far-Right view democracy as “absolutely important”, only 37.5% of the centre agrees.

Source: WVS

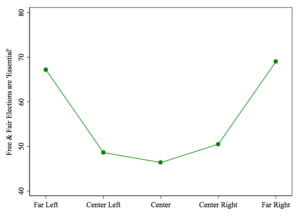

But perhaps this question is too abstract: respondents may not know what it means, exactly, to be governed democratically. To address this possibility, I turned to a more concrete question about democratic governance. How important is it, the survey asks, that “people choose their leaders in free elections”?

Here again, we find that support for democracy caves at the centre. Compared to 67% at the far-Left and 69% at the far-Right, only 46% of the centre believes that free elections are an “essential characteristic of democracy”.

Source: WVS

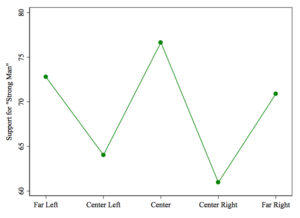

Finally, I turned to respondents’ attitudes toward authoritarianism. What do Brazilians think of “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament or elections”?

Once more, it is at the centre where authoritarianism finds its strongest support. A total of 76.6% – over three-quarters – of self-identified centrists view “strong” leadership as a “very good” or “fairly good” way to govern their country. In other words, these respondents are not just critical of democracy – they are actively enthusiastic for an authoritarian transition.

Source: WVS

On the topic of strong men, however, the differences between groups are significantly smaller. Seventy-two per cent of the far-Left support a strong leader, and 70% of the far-Right. Even among respondents who sit at centre-Left and centre-Right, overall support does not dip below 60%.

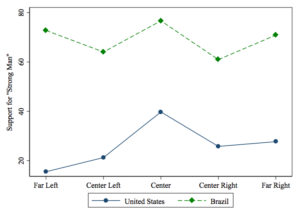

Such widespread support for strongman politics is staggering. Compare Brazil’s numbers to the United States, where less than 28% of respondents view this system of governance favourably. In Brazil, just one-tenth of all respondents believe that a strong man who does not bother with parliament or elections is, in fact, “very bad”.

Source: WVS

These figures provide an important clue to Bolsonaro’s success and the trends are backed up by more recent evidence. Nostalgia for Brazil’s military dictatorship is on the rise: according to a 2017 poll, 43% of Brazilians support bringing it back, compared with just 35% a year earlier. Their nostalgia heavily favours Bolsonaro, who has long considered himself a torchbearer for Brazil’s dictatorship. “Voting won’t change anything in this country. Nothing!” he screamed back in 1999. “Things will only change, unfortunately, after starting a civil war here, and doing the work the dictatorship didn’t do.”

The data on democratic attitudes, of course, cannot tell the whole the story. Bolsonaro’s candidacy has also been bolstered by a general wave of anger toward the political class. According to one recent survey, roughly a third of Brazilian voters were planning to cast a null vote in the presidential election. Bolsonaro – who has positioned himself as an outsider, railing against the corruption of Brazil’s political establishment – feeds from their negative partisanship. There, are, then, both push and pull factors at play.

But the findings from the World Values Survey suggest that Bolsonaro’s is not a coalition of crazies – lashing out from the margins of society – but one of “sensible” people. Election polls paint this profile in striking detail: Bolsonaro voters are on average wealthier, better educated, and more urban than Haddad’s.

In other words, he is consolidating precisely the constituency that most commentators in advanced democracies like Britain believe to be the backstop against authoritarianism. This is one of the key takeaways from the Brazilian election: our faith in the middle class is misplaced. Strongmen often find support among middle-class moderates, who trust them to advance middle-class interests against the redistributive preferences of the poor.

Even before taking office, Bolsonaro is rewarding them for their support: the stock market soared after his first-round victory, and Brazil’s business community is “rallying around” his candidacy.

In Brazil, we are reminded that capitalism and democracy have no inherent compatibility. Above all, markets love stability, and authoritarians love to promise it. In this sense, the Brazilian story is not so far from the American one. In the election of Donald Trump, we saw a radical candidate convince millions of moderate voters that Right-wing authoritarianism was the best bet for their policy priorities.

From one angle, this looked like the radicalisation of the centre ground. From another, though, it was a revelation that the centre ground was never committed to moderate principles in the first place.

The primary difference between these cases, then, is historical context. The Trump presidency, for all its madness, has not been able to undo two and a half centuries of democratic consolidation: the roots are simply set too deep for such sudden change.

Brazil’s democracy, by contrast, is in its infancy: it is less than 30 years since its constitution was ratified. If elected next week, Bolsonaro may well rip these shallow roots from the ground, inaugurating a period of darkness, violence, and political repression across the country. Whether by cluelessness or conviction, Bolsonaro’s base is bringing Brazil to the brink.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe