Jair Bolsonaro – the candidate who has called for civil war, cheered violence against women, trashed the free press, threatened to beat up homosexuals, and proudly proclaimed disrespect for the democratic process – will be the next president of Brazil. Having secured a whopping 46% of the vote in last week’s election – just shy of an outright majority – his only hurdle is the run-off election against the Workers’ Party (PT) candidate, Fernando Haddad, on October 28.

Haddad, for his part, looks hopeless. On Monday, his own campaign event turned against him, as a planned endorsement from the Democratic Labour Party candidate Ciro Gomes spun into a diatribe about Haddad’s failings. “You’re going to lose the election, and it’s your fault,” Gomes shouted.

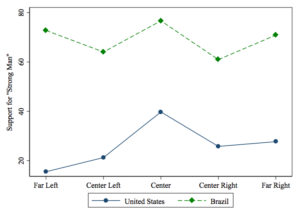

Bolsonaro’s spectacular rise raises key questions about the appeal of authoritarianism – in Brazil and around the world. Who constitutes Bolsonaro’s base? Why are they turning toward such violence and bigotry? And what can it tell us about new populist movements emerging in advanced democracies today?

To make sense of these questions, I revisited the data from the World Values Survey (WVS), collected in over 60 countries between 2010 and 2014. Focusing on the sample from Brazil, I examined the relationship between respondents’ self-placement on a left-right spectrum — ranging from 1 to 10 — and their support for democracy.

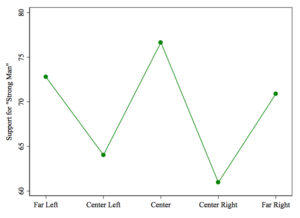

The main finding? It is moderates, not extremists, who are most excited about authoritarianism in Brazil.

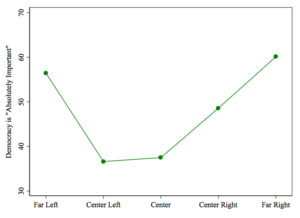

I began my analysis by looking at general attitudes toward democracy. The survey asks: “How important is it for you to live in a country that is governed democratically?”

Plotted against the Left-Right spectrum, the responses form a striking V-shape. People who identify at the extremes of the political spectrum are far more likely to value democracy than those who identify at the centre. While 56.4% of the far-Left and 60% of the far-Right view democracy as “absolutely important”, only 37.5% of the centre agrees.

Source: WVS

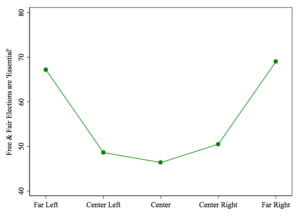

But perhaps this question is too abstract: respondents may not know what it means, exactly, to be governed democratically. To address this possibility, I turned to a more concrete question about democratic governance. How important is it, the survey asks, that “people choose their leaders in free elections”?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe