Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s Commissioner for Competition has not been afraid to tackle the tech giants. Thierry Monasse/DPA/PA Images…

This is the final part of a three-part series exploring the ills that have put ‘western capitalism on a knife-edge’. It follows Tuesday’s analysis of escalating CEO pay and yesterday’s focus on how an undeserving rich are protected from becoming poorer.

America’s Gilded Age was one of rapid economic growth. A period from the 1870s to the turn of the 20th century when new technologies and business models led to rapid innovation. It was also one, however, which concentrated wealth and power in the hands of just a few. An age characterised by ruthless but unfair competition. When monopolies dominated and politicians bowed to their power. When corruption was common and inequality extreme. Named after Mark Twain’s and Charles Dudley Warner’s 1873 book The Gilded Age, it is an apt description of a glossy surface hiding something a whole lot murkier. And it is as applicable today as it was 150 years ago.

The new Gilded Age

Cornelius Vanderbilt, for whom the modern use of the term robber baron was coined, started out captaining a ferry service in New York in 1817. Through cutting costs, using predatory pricing, and delivering a superior service, Vanderbilt broke the existing monopoly. It was a business approach that would became his highly successful modus operandi as he built his corporate empire, moving from steamships to railroads – but for him, breaking monopolies meant destroying or consuming competitors. Vanderbilt, along with his fellow ‘captains of industry’ – the familiar names of JP Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller – exploited their power and wealth to reinforce their own monopolistic dominance. “Law! What do I care about the law?” Vanderbilt asked, “Ain’t I got the power?”

The benefits of their endeavours are plain to see: railroads connecting communities, electric power and lighting, bridges and skyscrapers built with mass produced steel. Advances which were the product of determination, ingenuity and hardwork. But just as incomes grew, so too did inequality and social division. From this the Progressive Era was born, seeking to alleviate the worst social injustices of industrialisation.

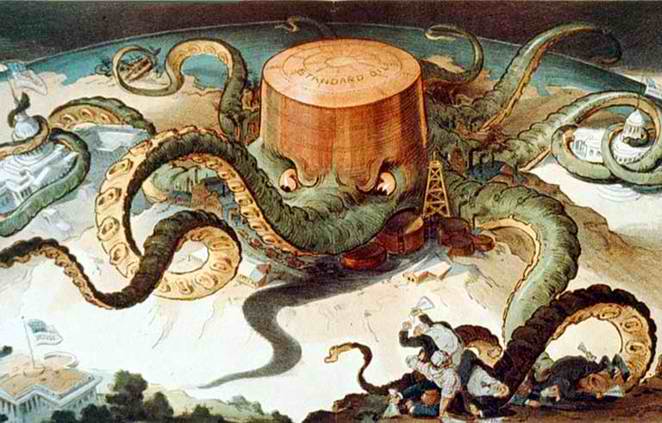

In the White House, President Theodore Roosevelt sought to tackle concentrated power and monopolistic greed through anti-trust legislation. He and his successor William Howard Taft broke up many of the country’s most powerful companies, including Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. As Liam Halligan sets out today – in his column on the investigative journalist and anti-trust campaigner Ida Tarbell – it was a popular move that placed Roosevelt on the side of the people and against corrupt trusts and their octopus-like power over American life (see cartoon below). It was this popularity, reflected in the President’s success in the 1902 Congressional elections, that enabled him to deliver such sweeping reform.

The characteristics of the Gilded Age are mirrored today. New technologies such as robotics and artificial intelligence are promising advances in every area of life, from healthcare to leisure. New business models, built on the gig economy, are delivering cheaper services for consumers. Just as the 19th century’s monopolies connected people physically, today’s monopolies connect people virtually – creating massive businesses in the process.

But as the super salaries of the top 1% soar, and average wages stagnate, inequality is casting a deep shadow over capitalism. In America levels of inequality are now in line with that of the gilded age.

Are tech giants the new ‘robber barons’?

Today’s tech giants resemble those late 19th century monopolies in key respects: Facebook, for example, owns 77% of mobile social traffic, Google 88% of search advertising.[1. Rana Foroohar, ‘Release Big Tech’s grip on power’, Financial Times, 18 June 2017] More than 40% of online retail sales in the US go through Amazon.[2. ‘Amazon accounts for 43% of US online retail sales’, Business Insider UK, 3 February 2017] Undoubtedly they have delivered significant benefits through their innovation and efficiency. Google has democratised information, and Amazon has made selling goods immeasurably easier, while consumers have benefited from lower prices.

Innovation is not the only trademark of the tech giants, like the industrial titans of a previous age, they too have sometimes built their continued power upon predatory tactics, lobbying and crony capitalist behaviour.

Aggressive acquisition strategies, made possible by their huge cash surpluses, have reinforced their market dominance.

- In 2015, Time magazine reported spending on tech acquisitions reached $170 billion the previous year, double that spent in 2010.[3. Victor Luckerson, ‘How Google Perfected the Silicon Valley Acquisition’, Time, 15 April 2015]

- Google purchased YouTube at a cost of $1.65 billion in 2006. Now, more than 1.5 billion logged-in users visit the site each month.

- In 2014 Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19 billion – the messaging service which now has over 1 billion users.

- Amazon intends to buy Wholefoods for $13.7 billion.

The tech giants are neutralising much of their competition and massively extending their reach by gobbling up rivals.

Google’s behaviour is under increasing scrutiny. Last month, Margrethe Vestager, the European Union’s competition commissioner, fined the tech giant a record-busting $2.7 billion for abusing its power in promoting its own shopping service, ordering it to change its practice. In her essay for UnHerd, Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson cited Vestager as a model for other defenders of capitalism to emulate.

Google is also awaiting the results of two other EU anti-trust cases against it. South Korea, Turkey and India are also investigating the internet giant.[4. Sally Hubbard, ‘Seven Reasons Why Europe’s Antitrust Cases Against Google Are A Big Deal’, Forbes, 16 March 2017] In response to a Russian case, Google was fined and forced to offer Android users a choice of search engines, thereby breaking their stranglehold on smart phone browser provision in the country.[5. Sarah Perez, ‘Google reaches $7.8 million settlement in its Android antitrust case in Russia’, TechCrunch, 17 April 2017] As America’s Fair Trade Commission has argued: Google’s “conduct has resulted – and will result – in real harm to consumers and to innovation”.[6. Matt Weinberger, ‘Government investigators wanted to sue Google after finding ‘real harm to consumers’ back in 2012’, Business Insider UK, 19 March 2015]

And it’s not just Google. Germany is currently investigating Facebook. Amazon has already agreed to change its publisher contracts to end an EU antitrust investigation. But noone yet seems bold enough to follow in Roosevelt’s footsteps and break up the tech giants.

A too-cosy-for-comfort relationship between business and politics is undermining trust

Crony capitalism is one of the most pernicious problems facing free enterprise. Just as in the Gilded Age, the unhealthily close relationship between business and government is undermining public trust. Polling by Ipsos found 72% of Brits, 65% of Germans and 74% of Americans agree their government “does not prioritise the concerns of people like me.”[7. Global Trends, Ipsos, 2017] Very similar levels believe the economy of their country is rigged in favour of the “rich and powerful”.

Cronyism can be seen in the scale of lobbying, the revolving door of employment and the eye-watering level of political donations. President Donald Trump wasn’t wrong when he talked of a need to “drain the swamp”.

In 2016, according to the Centre for Responsive Politics, $3.15 billion was spent on lobbying. The top spending sector was health at $515.5 million, unsurprising given the focus on the future of Obamacare. Finance, insurance and real estate were not far behind, approaching a half a billion spend. In April this year, The Times reported that FTSE 100 companies had spent at least £25 million on lobbying activities in Brussels and Westminster.[8. Alex Ralph, Harry Wilson, Times Data Team, ‘Big business spends £25m on lobbying politicians’, The Times, 15 April 2017]

It was lobbying by internet companies – and the threat of a co-ordinated service blackout – that killed the US Stop Online Piracy Act, despite the bill’s bipartisan support. Google collected more than seven million signatures on a petition posted on its high-traffic homepage.[9. ‘SOPA explained: What it is and why it matters’, CNN Money, 20 January 2012] “The voice of the Internet community has been heard”, said one Congressman[10. John Gaudiosi, ‘Obama Says So Long SOPA, Killing Controversial Internet Piracy Legislation’, Forbes, 16 January 2012] – obviously more loudly than the voice of those wanting stronger copyright laws, like Hollywood. Perhaps due to the greater popularity of the tech firms – YouGov polling for UnHerd found almost 60% of Americans think tech firm owners deserve their wealth, whereas less than a third think Hollywood actors and directors do. And 40% of Americans think big tech companies are more good than bad, compared to just 22% who think the opposite.

Lobbying is a big bucks industry:

- The murky relationship between politics and finance in the UK has been highlighted by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. In the wake of the financial crash, as Parliament was taking key policy and regulatory decisions, the Bureau revealed that in 2011 the financial services industry spent almost £93 million on lobbying.

- In 2012, they analysed the register of interests for the House of Lords, finding 16% of active peers either held positions at finance firms or had financial services clients. Of the 11 members scrutinising the 2011 Finance Bill four held positions at banks, with a fifth about to take up a position.

- As the US was scrutinising its own legislative and regulatory framework for the industry, The Centre for Public Integrity published analysis in 2010 that found half of the financial reform lobbyists had previously worked in the legislative or executive branch.

In the UK, some politicians’ willingness to abuse their power to help businesses was exposed by Channel 4’s 2010 Dispatches documentary which recorded members of parliament offering to sell influence – former Cabinet minister Stephen Byers referred to himself “a sort of cab for hire”.

Political donations are another source of distrust. A 2015 poll found 66% of Americans believe the wealthy have more influence on elections and 84% think money has too much influence in political campaigns.[11. ‘Americans’ Views on Money in Politics’, The New York Times, 2 June 2015] For many individuals, their donations reflect a legitimate desire to support a cause, but the dependency of individual politicians and political parties on securing donations raises understandable questions about political independence. One analysis found that in the last two years of their term, a typical US Senator spends two-thirds of their time fundraising.[12. Jasper McChesney, ‘How Much Time Do Congress-Members Spend Fundraising?’, bulletin.represent.us, accessed 26 July 2017]

In the UK, the reputation of the House of Lords has been diminished by the elevation of big party donors. Then Prime Minister Tony Blair was formally interviewed by police during an investigation into so-called cash for honours (no charges were brought). A 2015 paper by the University of Oxford’s Department of Economics found a significant relationship between donations and nominations to the Lords.[13. Andrew Mell, Simon Radford and Seth Alexander Thévoz, Is there a market for peerages? Can donations buy you a British peerage? A study in the link between party political funding and peerage nominations, 2005-14, Department of Economics, University of Oxford, March 2015]

In the Gilded Age bribery and corruption were common. Today’s crony capitalism may be legal, but it reinforces the feeling of an undeserving elite, operating in their own interests at the expense of the majority. Overall, as Ruth Davidson noted, producer interests “out-muscle consumers in the lobbying of parliament and government.”

Business is manipulating policy and regulation for its own ends

A meaningful relationship between business and government is key to economic prosperity. A strong private sector means wealth creation, and that means jobs and taxes to fund public services. Government should champion free enterprise, but it must do so as an independent arbiter. As Roosevelt recognised, government must set fair and transparent rules within which markets operate. Big business capturing the policy or regulatory process undermines that fairness. Today it can be seen in costly sector subsidies, generous tax breaks and inappropriate regulation.

Again, the tech giants prove a case in point. A 2016 report on data centre subsidies, for example, found that Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Apple and Amazon Web Services had benefited from $2 billion in subsidies, with eleven megadeals working out at a cost of almost $2 million per job. The author argues that taxpayers’ money is being paid to companies “to do what they were already planning to do.”[14. Kasia Tarczynska, Money Lost to the Cloud. How data Centres Benefit from State and Local Government Subsidies, Good Jobs First, October 2016] And it is worth remembering these companies are hoarding cash: in 2015 Moody’s reported that Apple held $216 billion in cash, 93% of which was overseas, Google held $73.1 billion, 59% overseas, and Microsoft held $102.6 billion, 94% overseas.[15. Levi Sumagaysay, ‘Apple, Microsoft, Google, Cisco, Oracle hold the most cash: Moody’s report’, Silicon Beat, The Mercury News, 20 May 2016]

Complex banking regulation is another example of big business using its power to reinforce its position. As Professor Avinash Persaud argued in a 2005 Gresham College lecture:

“Big business loves complex regulation. For a start, only they understand it.”

And complying with that regulation can cost millions. Such regulatory capture significantly increases the barriers to challenger banks breaking into the market and disrupting incumbents. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis found the relative costs of compliance are higher for banks with smaller assets.[16. Drew Dahl, Andrew Meyer, Michelle Clark Neely, Scale Matters: Community Banks and Compliance Costs, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July 2016]

This form of rent-seeking is no less damaging to capitalism than sky-high executive pay, it perverts the functioning of free markets, benefiting the provider over the consumer. Big businesses are profiting from advantages they haven’t earned, using their wealth and power to protect their dominance. Politicians are at best failing to hold them to account, at worst they are complicit in rigging the system in favour of corporate vested interests. Crony capitalism and monopolies are the enemy of free enterprise. It’s time to replace the new Gilded Age with a new Progressive Era….

But where is the Roosevelt of our time?

***

> This article is the final instalment in a three-part series on the challenges facing capitalism. Part one was published on Tuesday and part two was published yesterday.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe