Shorty after the crash, Lord Myners, then a Minister in the UK Treasury and himself a former banker, criticised shareholders for behaving like “absentee landlords”, abdicating their responsibilities to challenge pay and behaviour. The madness of a business owner allowing their staff to set their own pay is obvious to most, yet despite the so-called “shareholder spring” this year, few FTSE 100 businesses have lost votes on pay.

Shareholders should think again. Analysis by Marianne Bertrand and Sendhill Mullainathan found that in companies with poor governance, CEOs typically pay themselves more for improvements in profit which arise from luck. They are also more likely to award themselves stock options at lower cost. Adding a large shareholder to the board led to a sizeable reduction in pay for luck, for example, by 23-33%13.

The relationship between pay and performance is broken

Ironically, in a model where compensation is increasingly linked to stock value, the rewards senior bankers receive bare little relation to sustained performance. Instead, incentivising short-term profit maximisation leads to reckless behaviour of the sort that brought about the financial crisis.

Recruiting and keeping talent is core to any business, and generous pay packages are one way of competing for the best. ‘Star’ traders in particular are coveted by financial institutions who believe their individual brilliance will deliver millions in profits. Todd Edgar, for example, was reportedly enticed to move to Barclays from JP Morgan with a two-year £30 million cash and shares package for him and his team.

But star performance is often about more than the individual. One study looked at the performance of ‘star’ investment analysts when they transferred from one bank to another14. Rather than justifying their sky-high pay packages through improved company performance, 46% of those so-called stars performed worse in the first year, generally by around 20%. And far from being a transitional blip, performance was still lower after five years. On top of that, the study found hiring stars had a negative effect on a company’s stock price. The authors are clear: “companies cannot gain a competitive advantage by hiring stars from outside the business”. Yet firms are competing for these ‘masters of the universe’, driving pay packages that are more and more extravagant.

There is no reason to think this hubris is confined to the financial sector, though the pay packages there are the most extreme. The authors of the ‘stars’ study extended their analysis to look at twenty top General Electric managers who took up top jobs elsewhere, finding similar problem with the portability of stardom15.

Tellingly, another academic paper found that when new CEOs are appointed and paid less than standard for the industry and company size, share performance is roughly average. But when CEOs are appointed on above average packages, they deliver lower returns: “excess pay appears significantly negatively linked to forward profitability”16.

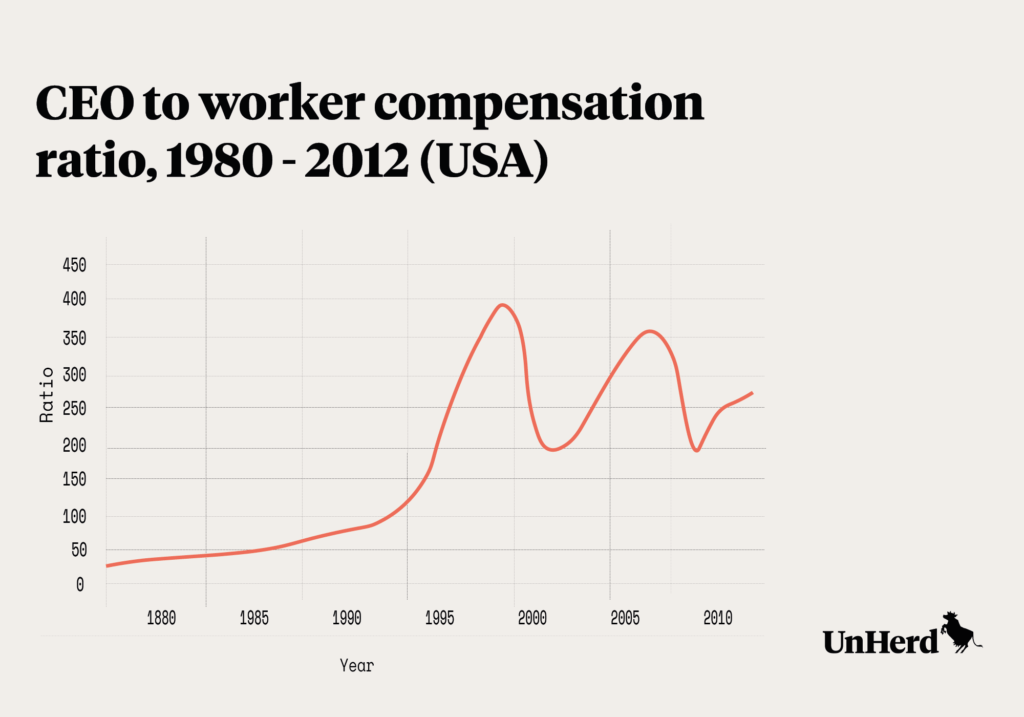

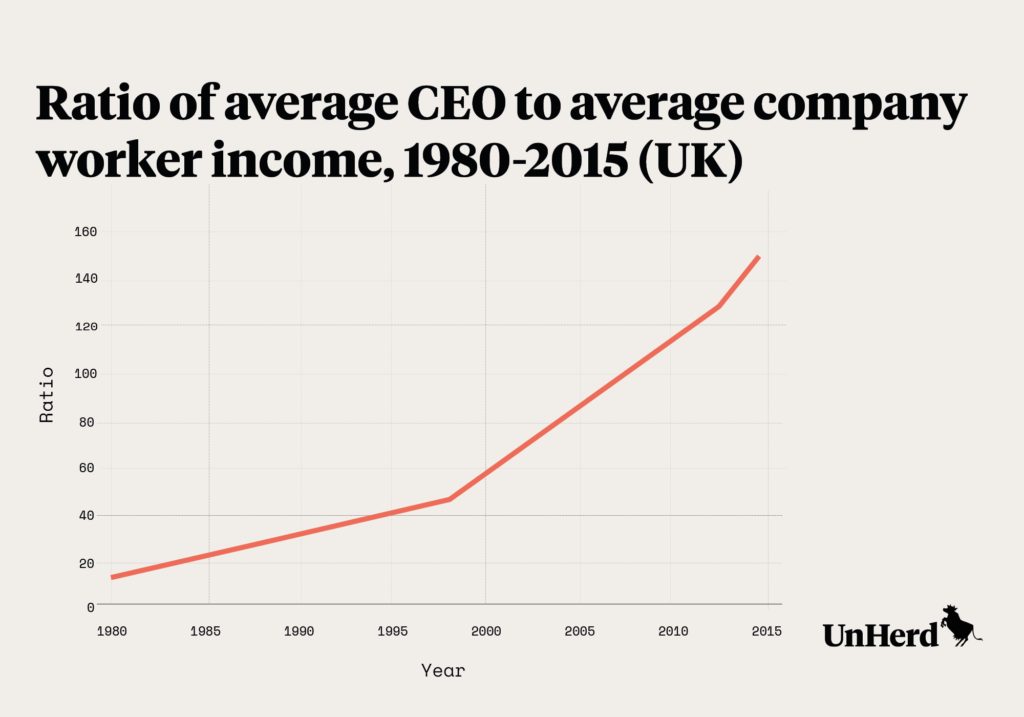

Capitalism works when it benefits the majority. When wealth creation appears to accrue to an elite few, capitalism appears not as a force for good, but a force for greed. Gordon Gekko writ large. The financial crash vividly exposed the “fat cats” as undeserving of their sky-high pay and that their high pay encouraged them to act unwisely. Their reckless behaviour cost millions of ordinary people their jobs, homes and life savings. And yet a decade on, the gap between executive pay and the wages of ordinary workers is almost as wide as before the crash. If public faith in capitalism is to be restored, the connection between pay and performance must also be restored. Executive pay must be brought under control. Capitalists must themselves end the era of the undeserving rich.

This article is the first instalment in a three part series on the challenges facing capitalism. The second part will be published tomorrow.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe