Credit: Getty Images / Mario Tama

> This is the second part of a three-part series – following up yesterday’s analysis of escalating CEO pay

78% of Americans and 76% of Brits believe “the economy of my country is rigged to advantage the rich and the powerful”.1 Over 70% of Germans, Australians, Canadians and the French agree. The financial crisis exposed a fundamental flaw in today’s capitalist model: it favours an undeserving rich. Capitalism is in crisis because people no longer believe it works for the many.

The bankers responsible for the crash have not been punished

When the financial sector imploded due to the reckless behaviour of some bankers, serious consequences were expected. The public understood the immediate need to stabilise the financial system (more people than not believe the crash would have been worse without the bailouts),2 but they also expected those responsible to be held to account. Wrongdoing, it is commonly understood, should be punished. Instead, while the banks received billions of taxpayers’ money and senior executives generous exit payments, millions of those taxpayers lost their jobs, their homes and their life savings.

The top five executives at Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, two investment banks that collapsed, were paid around $2.4 billion between 2000 and 2008. Harvard academics who analysed this eye-watering pay concluded that while the executives made considerable personal losses when their firms failed, these losses were outweighed by the huge “performance” bonuses they had already received.3 Richard Fuld, CEO of Lehman Brothers, earned $466 million in the eight years before the 158-year-old bank filed for bankruptcy.4 He took home over $61.5 million in cash bonuses alone between 2000 and 2008. James Cayne, who as CEO of Bear Stearns presided over a £1.7 billion loss, received almost $390 million between 2000 and 2007 – over $87.5 million in cash bonuses.5

Almost a decade on, those involved in precipitating one of the biggest recessions in history appear to have got off scot-free. In the US, just one Wall Street banker, a senior trader at Credit Suisse, has been jailed for his actions. As yet, not a single UK banker has been jailed as a result of the crash. Prosecutors have argued that poor judgement, or immoral behaviour, does not mean laws have been broken. But questions are rightly being asked about their willingness to press charges. The authorities in Iceland have successfully jailed 26 bankers, including the most senior executives.

Analysis by investment bank Keefe, Bruyette and Woods in 2015 found 49 financial institutions had collectively paid government entities and private individuals $190 billion in fines and settlements since 2009.6 The scale of these payouts suggests pretty sizeable wrongdoing.

America’s Department of Justice has itself extracted huge financial settlements. JP Morgan Chase, for example, paid $13 billion in 2013. And in the process, like many other banks, avoided public exposure of the activities that warranted such a large payout. Fortune magazine estimates JP Morgan Chase made a profit of $22 billion that year – and the bank’s stock price rose by 30%.7

The idea that banking executives are ‘too big to jail’ reinforces the sense that the rich live by a different set of rules. No wonder YouGov polling for UnHerd found just 5% of Britons and 12% of Americans think those responsible for the financial crash have been appropriately punished.

The rich can’t get poorer

It is bad enough that justice has not been served. That those responsible for such catastrophic failure also remain rich is unbelievable, showing just how corrupted the current model of capitalism has become. Stan O’Neal’s firing as CEO of Merrill Lynch after announcing a $4.5 billion8 write down was cushioned by a $161.5 million payoff. Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince was awarded a $28 million golden goodbye. In the UK, Fred Goodwin presided over the implosion of RBS, and while waiving his right to a £1.29 million payoff, eased into unemployment with a £700,000 a year pension (accepting a reduction to £342,500 after public outcry) – made possible by a bail-out of over £65 billion in taxpayer funds.

And rewarding failure extends well beyond banking. The Institute of Policy Studies analysed the performance of 241 American corporate CEOs who had ranked in the top 25 highest paid between 1993 and 2012.9 Corporate stars whose value to their firms supposedly justified their astronomical pay. In fact, nearly 40% of these highest paid CEOs were “bailed out, booted, or busted” – the latter meaning they had to pay significant fraud-related fines or settlements. Examples of CEOs fired include Hank McKinnell of Pfizer who was forced out in 2007 with a $116 million golden parachute and $82 million in retirement benefits. Pfizer stock declined 40% during KcKinnell’s five-year term.

For capitalism to work, success must be rewarded, but so too must failure be punished. The rich must be able to get poorer when they deserve to. That this isn’t happening helps explain why so many people believe the economy is rigged in favour of the elite.

Inequality is rising, and a super elite is becoming more and more detached

If capitalism perpetuates a “rigged” system, proponents of free enterprise should not be surprised that the arguments of anti-capitalists resonate. From Tsipras in Greece to Corbyn in the UK, Melenchon in France and Sanders in America, hard-left platforms have garnered mass appeal.

The reckless behaviour of those involved in the banking crash concentrated people’s anger, but it is increasing outrage at levels of inequality that has allowed socialist parties to gain traction. The disillusionment with capitalism has allowed economists like Thomas Piketty to mainstream the view that capitalism inevitably leads to deep, and destructive, inequality.

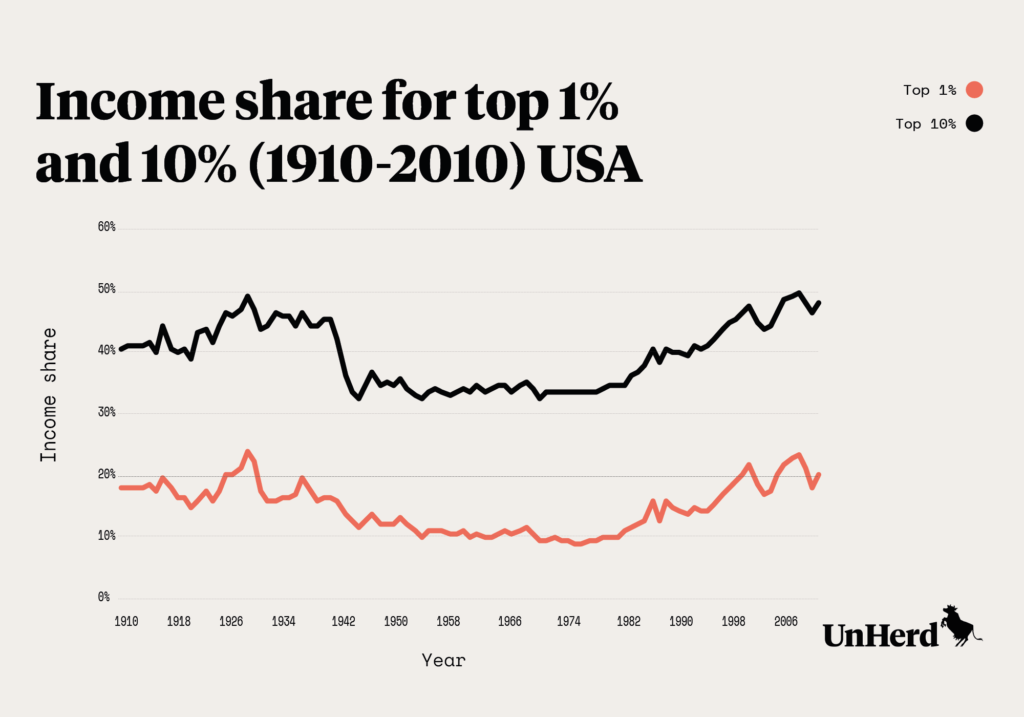

Certainly, the gap between rich and poor, both in terms of wages and wealth has been steadily increasing, driven by surging top pay, unequal savings rates and rising household debt.10 Between 1979 and 2011, the wages of middle-earning American workers grew by just 6%, compared to 37% for the top 5%. But it is the highest-earning 1% who benefited the most. Their wages rocketed by a massive 131%.11

Wealth, or asset, inequality is more extreme, particularly in the US. Between 1983 and 2010, 38.3% of wealth growth went to the top 1%, 74.2% to the top 5%. At the same time, the bottom 60% saw their wealth decline.12 In the UK too wealth is concentrated in the hands of the few – the top 1% hold 20% of household wealth and the top 5% hold 40%.13

But the real problem is a super elite detaching itself from even the top 1%. A 2014 paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that “almost all” the increase in US wealth inequality over the past three decades is due to that of the top 0.1%, whose wealth share increased from 7% in 1979 to 22% in 2012.14

And this extreme inequality has been exacerbated by government, reinforcing the idea of a “rigged” system. Quantitative easing and low interest rates in the wake of the crash have boosted the value of assets and lowered the cost of borrowing. The rich have become richer not through inventing new products or services, or through hard work and talent, but simply by being wealthy. At the same time, ordinary families have lived through almost a decade of austerity and lagging wages. In America, median household income rose for the first time since 2007 in 2015.15 In the UK, the real wages of average full-time workers are lower than in 2004. Economic recovery has been the preserve of the wealthy.

Capitalism is unfair

Today’s model of capitalism is not living up to the fundamental principle of fairness – that people earn what they deserve. Separate from egalitarianism, it is the idea that hard work, talent and ingenuity lead to success and that wrongdoing and failure lead to loss.

This sense of fairness is core to the Anglo-Saxon capitalist model. The World Values Survey asked people whether it is fair or unfair that a secretary who is “quicker, more efficient and more reliable” earns “considerably more” than another secretary doing the same job. Just 11.1% of America respondents, 16.1% of Germans and 18.8% of Canadians thought this scenario unfair.16

In the UK, a 2011 YouGov poll found that 85% of people agree that in a fair society income should depend on how hard someone works and how talented they are. When asked to choose between two statements defining fairness, “those who do the wrong things are punished and those who do the right things are rewarded” or “treating people equally and having equal distribution of wealth and income”, 63% chose the former, just 26% the latter.17

Against this definition of fairness, the Great Recession exposed capitalism as wanting: people doing the wrong thing were not punished, nor had they earned their rewards. The public do not begrudge James Dyson or Bill Gates their riches – the benefits to society of their ingenuity and hard work are plain to see. YouGov polling for UnHerd found 70% of Brits and 72% of Americans believe inventors of new products and services deserve to be wealthy. That cannot be said of the financial titans who in seeking to enrich themselves have made so many families poorer. Just 17% of Brits and 30% of Americans believe senior bankers deserve their wealth.

As Will Hutton argued in The Guardian in 2010: “big rewards are justifiable if they are in proportion to big efforts – because big effort grows the economic pie for everyone”, but the banking sector was not playing ‘fair’, it was shown to be “an old-fashioned rigged market by a bunch of smart insiders who have managed to get away with it for decades because hard questions were never asked about fairness or proportionality.”18 The future of capitalism depends on a willingness to ask those hard questions, and in doing so restore people’s faith in capitalism as a model for all.

This article is the second instalment in a three-part series on the challenges facing capitalism. The third part will be published tomorrow, part one was published yesterday.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe