Those who have listened to my Confessions will know that I have a problem with the idea of liberalism. To me, it has long been associated with individualism, with the prioritisation of the solitary self and individual rights, over and against the community.

I see family and community as the most successful support structures that history has ever known – especially for the most vulnerable. Detaching the individual from his or her place within a stable community renders them vulnerable to powerful economic forces, forces that identify the primary function of an individual’s life in terms of their economic significance and usefulness.

Liberalism is the handmaid of capitalism and capitalism a mechanism for turning people into cash machines for the 1% – with just enough benefit to the poor to make it logical for them to trade their community birthright for a slightly better paid job, often somewhere far away from where they grew up. Loneliness and alienation are the consequences.

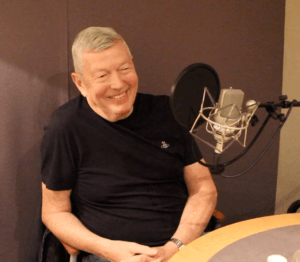

Now I know that this is only one side of the story, and that this narrative implies a sunny conception of community – a word that is often thrown about with great naivety. Which is why my Confessions with Alan Johnson was always going to be a challenge. For Johnson is not only a powerful cheerleader for a broadly liberal conception of the left – a Blairite, so to speak – but he also understands better than most that both community and family can be as much a threat as a support.

Now I know that this is only one side of the story, and that this narrative implies a sunny conception of community – a word that is often thrown about with great naivety. Which is why my Confessions with Alan Johnson was always going to be a challenge. For Johnson is not only a powerful cheerleader for a broadly liberal conception of the left – a Blairite, so to speak – but he also understands better than most that both community and family can be as much a threat as a support.

As he righty says, the values that keep a community together can also be the ones putting up signs that say “No blacks, no Irish” in shop windows, or cause domestic violence to be ignored. Those who describe themselves as post-liberal, as I do, ought to shut up a bit and listen again to the things he reminds us of – that community can also be a terrible thing, crushing, dehumanising and racist.

Can we articulate a version of community life that offers its members solidarity and support without denigrating outsiders? Can we describe a way of living together that values what our particular group has in common while, at the same time, being sufficiently porous to outsiders such that it welcomes the stranger and the outsider? This, I believe, is the great political dilemma of our times.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe