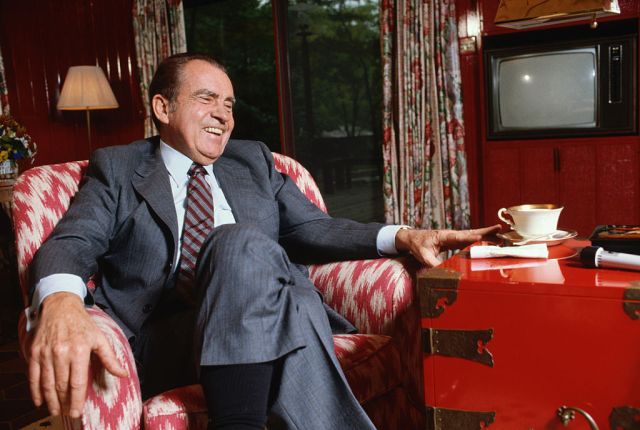

Nixon’s happier days. Wally McNamee/Corbis via Getty Images.

At home: disorder in the streets and a rising tide of drugs. Abroad: a shameful, humiliating withdrawal from an Asian outpost of empire. In politics: a conservative demagogue, backed by the silent majority, sweeps aside an ineffectual liberal stooge. In culture: fights over abortion, and women, and music, all conjuring a feeling that the republic is doomed. Am I talking about pot and Saigon and the sweep of Richard Nixon, or fentanyl and Kabul and the return of Donald Trump? I could be describing either, for both 1968 and 2024 feel like chaotically epochal years in the American story. Nor are these the only similarities between past and present. Just as in the Sixties, liberals today are faced with an urgent question: what now?

The answer, I think, is epitomised in a single book. Written by Ben Wattenberg and Richard M. Scammon in 1970, The Real Majority: An Extraordinary Examination of the American Electorate charted the political centre in the new Nixonian age. Over half a century on, it still offers deep insights for navigating a society in flux, even as it shrewdly leavens its electoral insights with clear and evocative language. Especially with Donald Trump the new American leviathan, moreover, The Real Majority offers another enduring truth — if liberals fail to occupy the heartland of American politics, wily conservatives will rush to get there first.

After their defeat in the 1968 election, Democrats pondered the future. The loudest insurgents were the so-called New Politics liberals, progressive activists who sought to push their party Leftwards. This meant replacing the New Deal coalition, anchored by middle-income voters, with the so-called McGovern coalition: a heady blend of youth voters, African Americans, the poor, and the educated middle class. Activists believed this grouping comprised a majority that could push the country in a more progressive direction.

Scammon and Wattenberg dismissed these ideas as arithmetically foolish — and therefore politically hopeless. Insatiable data hounds, they made psephology The Real Majority’s foundation. The authors knew all the relevant players across Capitol Hill, yet rejected cocktails with senators for slogs through the electoral weeds. As they put it: “It is voters, not insiders, who elect candidates.”

Not that any of this theorising is hard to unpick. On the contrary, The Real Majority makes its case with literary aplomb. “The great majority of the voters in America are unyoung, unpoor, and unblack,” is how the authors put it: “they are middle-aged, middle-class, and middle-minded.” A generation before algorithms micro-targeted soccer moms, Scammon and Wattenberg macro-targeted America’s archetypal Middle Voter. She wasn’t a peacenik anthropology major, but rather a 47-year-old housewife, married to a machinist in Ohio. Her concerns, not that of the activist class, comprised the real “center of American politics”.

Far more than a postmortem, then, The Real Majority offered Democrats a roadmap back to power, one obliging the party to abandon decades of ideological baggage. Since the Great Depression, after all, its power had rested on the issue of economic prosperity. Yet by the late Sixties, the glory days of the New Deal felt very far away. From violent anti-war protests to Black Power radicalism, the authors argued there was now a new core in American politics, one less focused on unions or wages, and more on social cleavages. In this unfamiliar new era, the duo therefore urged for New Deal activism in economics, but also toughness on these new-fangled cultural pressures. As the duo warned, if they failed to get serious on what they called the “Social Issue” then they could wave their electoral future goodbye.

This is hardly surprising. Through the Sixties, after all, rates of violent crime had doubled or even tripled. And yet like the 2020s, liberals responded by equating law-and-order with racism. In one memorable passage, the authors brilliantly evoked the bleating progressive activist, one depressingly resonant five decades on. “Lady, you’re not really afraid of being mugged; you’re a bigot.” On Vietnam, meanwhile, liberals hemmed and hawed before finally dismissing Americans as imperialists — when what they should have done was take charge and explained how they’d end the war.

These insights, so fresh then and so familiar now, didn’t come from nothing. On the contrary, The Real Majority’s intoxicating blend of clear-eyed policy prescription and psephological analysis can be traced straight back to its authors. For the former, we have Scammon to thank. Born in 1915, to upper-class parents in Minneapolis, the precocious youngster once organised the entire globe into voting precincts. The Second World War interrupted his doctoral work in political science. But soon enough, the young Captain Scammon was devising West Germany’s postwar elections. That prompted a stint in the State Department and a 1961 appointment to head the Census Bureau.

By the late Sixties, Scammon was the nation’s preeminent source on all things statistical: but still needed help translating his deep electoral insights into something more tangible. Enter Joseph Ben Zion Wattenberg. Born in 1933 to East European Jewish immigrants, he came of age in a Bronx hothouse of Leftwing Zionism. A writer and editor, he dabbled in children’s literature and trade journals, and failed in two runs for local office. By 1962, Wattenberg discovered Scammon’s Census Bureau and its decennial Statistical Abstract of the United States. Drawn to this compendium of numerical facts, Wattenberg interviewed and then befriended Scammon.

This partnership would soon spawn The Real Majority, a project aimed at saving liberals from themselves. Scammon’s data allowed them to see beyond the facile McGovern coalition, even as Wattenberg’s vivid penmanship turned mountains of data into a page turner. “To know that the lady in Dayton is afraid to walk the streets alone at night,” he evocatively explained, “to know that that her brother-in-law is a policeman, to know that she does not have the money to move if her new neighborhood deteriorates, to know that she is deeply distressed that her son is going to community junior college where LSD can be found on the campus — to know all this is the beginning of contemporary political wisdom.”

When the book was finally published, in the fall of 1970, it raced up the New York Times bestseller list. A restless political animal, Richard Nixon read pre-publication excerpts of The Real Majority with a mixture of interest and alarm. And no wonder: it was written by Democrats to defeat him, even as aides warned the book offered a “workable blueprint for our defeat”. A lengthy White House memo on the work soon circulated. “Republicans,” it cautioned, “cannot allow the Democrats to get back on the right side of the social issue.” Soon enough, this became official White House strategy for the midterms and beyond.

Nixon, in an act of political jujitsu, used The Real Majority’s blueprint to do the unthinkable: win blue-collar Democrats. Through the Social Issue, he built an enduring Republican majority, making liberals into allies of disorder. To achieve this, Nixon searched his bag of political tricks. After a rally in San Jose, California, the president’s advance team stalled his exit to coincide with the appearance of anti-war protesters. With his enemies moving in, Nixon muttered “this is what they hate to see” and leapt onto the hood of his limo, thrusting both arms upward into his trademark Double-V. The crowd howled obscenities and hurled stones, eggs, and vegetables. Finally, Nixon’s motorcade drove away through a hail of debris. Windows were smashed, aides frightened; but Tricky Dicky got the media images he wanted. The corpulent Donald Trump could only dream of such a stunt.

The San Jose stunt enabled Nixon to pillory his “thousand haters”. Aligning himself with the Dayton housewife, he called for an end to “appeasement” of the “thugs and hoodlums”. Decades later, you can still almost hear the Glendas of America nodding vigorously in agreement. Nor did The Real Majority’s influence end there. William Safire, a Nixon aide and amateur linguist, noticed a change in the national lexicon. “Elitism” and “permissiveness” — long relegated to academic jargon — entered the mainstream. Just as The Real Majority predicted, a backlash against disorder had taken root. This allowed Nixon to paint himself as the moderate defender of what he himself called the “silent majority”.

It took liberals far longer to grasp these lessons. In November 1972, George McGovern, the star of American progressivism and eponymous hero of that much-vaunted coalition, was thrashed by Nixon. In fact, the result would be the greatest landslide ever won by a Republican presidential nominee, with Nixon securing over 60% of the vote. The South Dakota senator’s antiwar activism, dovetailed with his support for universal basic income, may have thrilled the Left. But McGovern was, in the words of a political ally, the candidate of “acid, amnesty, and abortion”. As one Middle American bluntly told a journalist: “McGovern? He’s for dope.”

And if Democratic failure in the early Seventies soon paved the way for Reagan, The Real Majority is far from a historical artefact. For if our current moment has deep echoes to the late Sixties, the book remains eerily applicable to the age of Trump. Even now, the “great majority” of American voters remain “middle-aged, middle-class, and middle-minded”. That’s clear enough from the election last month: middle-income and middle-aged GenXers broke hard for Trump. To these Americans, inflation and crime outweighed the boutique worries of the activist class.

One enduring lesson of The Real Majority, then, is this: whoever wins the centre wins elections. Here’s another: if Democrats ignore Wattenberg and Scammon, repeating the mistakes of the New Politics and focusing on trans rights and climate catastrophism over bread-and-butter basics, conservatives will continue to dominate the national conversation. Even then, progressives aren’t sure to absorb the book’s wisdom. As Wattenberg once cracked, The Real Majority alienated “most every liberal in America — except those it converted”. Yet the facts are stubborn, whatever the year.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe