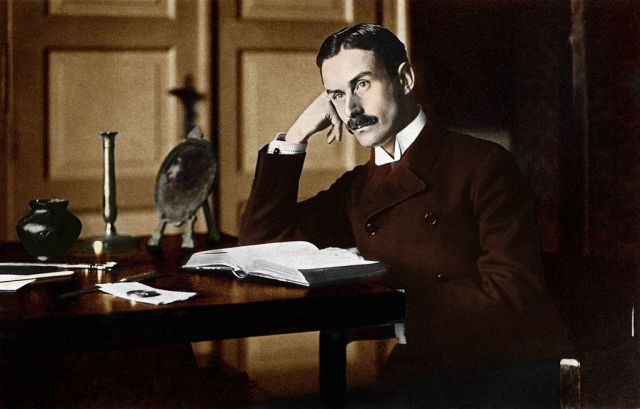

Thomas Mann dreamed up the story of Magic Mountain after a visit to a Davos sanatorium. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

“What was it, then? What was in the air? A love of quarrels. Acute petulance. Nameless impatience. A universal penchant for nasty verbal exchanges and outbursts of rage, even fisticuffs.” Near the end of his novel The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann presents its snowbound setting — a sanatorium for tubercular patients in Davos, Switzerland — as the microcosm of an ill-tempered age on the edge of an abyss of violence. “Every day fierce arguments, out-of-control shouting-matches would erupt between individuals and among entire groups; but the distinguishing mark was that bystanders, instead of being disgusted by those caught up in it or trying to intervene, found their sympathies aroused and abandoned themselves emotionally to the frenzy.”

In a novel crammed with uncanny premonitions of the century to come, Mann’s sketch of the dynamics of online polarisation now seems especially acute. Published exactly 100 years ago, in November 1924, The Magic Mountain unfolds in its highland Alpine enclave — a small world, but the whole world — between 1907 and 1914. We learn that the young marine engineer Hans Castorp from Hamburg, the naive, questing hero with a spot on his lung, will share the fate of his generation on Great War battlefields. Mann, already a German literary heavyweight thanks to his family saga Buddenbrooks and later stories such as Death in Venice, embarked on Hans’s story in 1913. He set it aside during the war, and only finished his epic amid the tumults of the early Weimar Republic. The project began as a compact comic tale but ballooned into a zeitgeist-defining behemoth that took the temperature of an entire civilisation — and issued a grim prognosis.

Make the long, but scenic, trek up Mann’s mountain, and you will be rewarded with vivid vistas of intellectual — and emotional — landscapes that have endured to the present day. Mostly composed when Hitler counted as a Bavarian beer-cellar ranter, and before Lenin’s regime in Russia had solidified into dictatorship, the novel presages, and models, a century of stand-offs, skirmishes, and brutal collisions, between competing world-views and ideologies that never quite triumph, but never quite surrender. That terminal moment of breakdown into “petulance”, when dialogue and disagreement fray into irreconcilable enmity, is a pivotal event. Until then, The Magic Mountain has staged a gigantic carnival of conversation between opposing principles — reform and reaction, health and sickness, flesh and spirit, lust and love, even (and above all) between life and death — that never entirely lose touch with each other. Now words will yield to deeds, chats to blows.

Peopled by a droll, picturesque cast of eccentric characters, the International Sanatorium Berghof isn’t just a political or philosophical talking-shop. Young Hans, whose ambiguous passions encode Mann’s own lifelong predicament as a married paterfamilias primarily attracted to men, must learn about body and soul, love and death, as well as history’s Big Ideas. His infatuation with the alluring Clavdia Chauchat, a central-Asian Russian with her “Kyrgyz eyes”, often makes him despise the abstractions of the sanatorium’s warring ideologues. And Mann always embodies his ideas in oddball characters, with the high-minded Italian liberal humanist Lodovico Settembrini, and the “caustic” Jesuit-trained (but Jewish-born) radical reactionary Leo Naphta, as first among equals. Later they will be joined, and dethroned, by a sinister but spellbinding Dutchman, Mynheer Peeperkorn.

Settembrini and Naphta are the two disputatious frenemies between whose poles the impressionable Hans bounces like a rubber ball. But they finally agree to settle their differences not, as before, over tea and wine or on hikes through the snow — but in a duel. Nothing except blade or bullet will resolve the endless arguments of liberal against conservative, freethinker against believer, progressive against reactionary. “The Absolute, the holy terror these times require,” thunders Naphta, “can arise only out of the most radical scepticism, out of moral chaos.” Only bloody convulsion will redeem a sick time.

With their weak lungs and strong opinions, Mann’s pair of senior wranglers gaze out from their mountain vantage-point over future decades of furious debate. The terms of the Settembrini-Naphta disputes have not really aged. If you’d tuned in, for example, to this week’s American presidential election, you would have found that liberals and conservatives, utopians and authoritarians, still go to rhetorical war armed with the weapons his antagonists deploy. Partisans continue to scrap in the same way that Mann’s Italian literary scholar, with his belief that “the powers of reason and enlightenment will liberate the human race”, does with the feline Jewish Jesuit, who maintains that flawed, sinful humanity craves “discipline and sacrifice” under the benign rod of a hierarchical authority. No other great novel of the 20th century punctures a pompous and hypocritical liberalism with such relish and cunning — at the same time as it demonstrates that the puncturing, at the hands of a ruthless and illusion-free “realism”, may pose a greater risk than the pomposity.

In an era once more beset by divisive wars of words, much of the book feels strikingly contemporary. Later writers who challenge its premises have echoed its procedures. In her newly-translated novel The Empusium, for instance, the Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk may probe Mann’s patriarchal blind spots with scenes of self-satisfied chinwags among bloviating blokes who believe that “a woman can only develop and retain her identity within the sphere of a man”. Still, her feminist take-down — which transfers the venue to pre-1914 Prussian Silesia — also acts as a spirited homage. Mann’s principal figures survive: Settembrini becomes “August August”; Naphta, “Longin Lukas”.

In any case, part of Mann’s evergreen genius is to show how, in ideological debates, binaries will tend to blur and categories crumble. His two champions intellectually cross-dress. They wrap themselves in contradictions. Both men’s gyrations now sound thoroughly familiar from social media, TV panels or campaign trails — early stirrings of the political whirlpool where liberationist progressives demand strict surveillance of words and deeds, while upholders of strong faith-based authority foment distrust, resentment, even insurrection. In an age of ever-proliferating polemics, warring camps may undermine not just one another but themselves. Naphta gleefully skewers Settembrini’s dream of a “capitalistic world republic” that champions freedom for both individuals and states but will require an all-powerful “bourgeois court of arbitration” to maintain harmony and control. Universal liberties will need, he insists, rigorous and intrusive policing.

As for the “democratic empire” of equality and progress for which the Italian idealist yearns, it rests on one absolute deity: money, whose tyrannical power is now “making life a veritable hell”. Among Mann’s many prophetic ironies, none feels more piquant than his decision to set The Magic Mountain in Davos. Now, each snowy January, a legion of plutocrats land there with their PR retinue of spinning Settembrinis to mix unelected power-brokering with liberal-democratic pieties at the World Economic Forum.

If Naphta exposes the muddles of Settembrini’s progressive humanism, he reveals some flagrant paradoxes of his own. With spooky prescience, Mann shows that the Jesuit’s devotion to divinely sanctioned unity and order might, in modern conditions, take the form not of stable conservatism but radical fervour. The reactionary morphs into the revolutionary. No passage strikes more of a knockout blow than the dawning realisation that Naphta’s disdain for “the political ideology of the bourgeoisie” has led him to espouse “the necessity of terror”. And that, at present, terror must take the form of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Bolshevism will hasten the advent of the anti-capitalist City of God. His church had always “inscribed radical overthrow upon its banner — destruction, root and branch”. Now, that banner may righteously be coloured in the deepest red.

Even in the early Twenties, Mann kept the keenest of eyes on the followers of both Hitler and Lenin. He saw, far earlier than most, how the foes of bourgeois liberalism might catch their common enemy in a vicious pincer movement. Naphta rails against the hypocrisy, duplicity and inequality of liberal humanism — “the freedom that has ruined the world” — in language found today more often on the Left than on the Right. And as often in the East as in the West: the recent Brics summit in Kazan gave the latest focus to Naphta-style arguments about the false claims and double standards of Euro-Atlantic corporate democracy. Meanwhile, the Jesuit’s invective against the illusion of “objective science”, and his contention that all secular knowledge and culture merely serves sectional interests, rhymes neatly with the anti-universalist doctrine of radical academia today.

Mann undoubtedly gives the witty, corrosive Naphta most of his best tunes. The character we first perceive as an arch-reactionary was actually derived not from any Right-wing thinker but from the Marxist critic and philosopher Georg Lukacs, who revered Mann. As for Mann, he felt, then dramatised, the Marxist’s hypnotic eloquence: he wrote of Lukacs that “For as long as he spoke he was right.” In comparison, Settembrini — “forever tooting his little horn of reason”, Hans thinks — comes across as a prolix and puffed-up bore. His mindset of “shabby bourgeoisosity”, with as “its sole objective… for a person to grow old, rich, happy and healthy”, lacks the stardust of heroism. Meliorist democracy looks, and sounds, dull and plain next to the glamour and danger of transformative upheaval. Maliciously, Mann gave Settembrini the rhetorical tics as his older brother (and fellow-writer) Heinrich, much more of a conventionally “progressive” public figure.

Naphta scorches, and seduces. Still, Mann understands that Settembrini should prevail. His own faith in democratic liberalism was no foregone conclusion. During the Great War he had written a grandiose tract in favour of a mystical German nationalism: his tortuous Reflections of an Unpolitical Man are far from the neutral testament that disingenuous title suggests. But by October 1922, when he gave a landmark speech in Berlin “On the German Republic”, he had made a lasting peace with democracy. Now, and ever after, he nailed his colours to the pluralistic mast as a Zivilisationsliterat: a member of the liberal literati. These days, some might just say “woke”. From the late Twenties, National Socialist propagandists sneeringly referred to his liberal disciples as the Thomasmänner, the Mann men. Their inspiration would leave Hitler’s Germany for exile as early as March 1933.

For Hans, Settembrini comes to stand for light, and life; Naphta for darkness and death. The latter realm still tempts him but, stranded in a snowstorm after a rash skiing expedition, Hans comes to acknowledge that “For the sake of goodness and love, man shall grant death no dominion over his thoughts”. However, The Magic Mountain assumes that the principles of life and death, freedom and order, will always need each other. Settembrini without Naphta subsides into flabby and invertebrate windbaggery — but Naphta without Settembrini may drown the world in fear and hate. The dialectic is all.

Readers might conclude that an insipid liberalism depends on the vigour of an abrasive, sceptical conservatism to keep it on its toes. Maybe: but that takeaway reckons without Mann’s late arriving curveball. Just when we, and Hans, imagine that the Naphta-Settembrini discussion group can trudge on forever across the white slopes of Davos, along comes Mynheer Peeperkorn. This stupendous Dutchman, a wealthy retired coffee planter from colonial Java, adds an even more timely voice to the mountain’s debating chamber. Peeperkorn represents politics, and power, as pure “personality”. He is deeply stupid, and deeply charismatic. Call him Reagan, call him Trump, call him Corbyn if you wish: in him, ideology melts into mushy uplift while a vague verbiage (“By all means! Permit me to say —settled!”) leaves his listeners bewitched. Temporarily, he unites Naphta and Settembrini in mystified contempt at this “hocus-pocus of insinuation and emotional charlatanry”. Yet, fatally, this brainless enchanter has “killed the spark” of their dialogue. “Nothing crackled between the antagonists now, no lightning flashed, no current surged. The presence that intellect thought to neutralise, neutralised intellect instead.”

Some critics view Peeperkorn as a Hitlerian figure. Although scary as well as absurd, his bumbling, stumbling air of unearned profundity has more in common with the folksy content-lite populism — offered from Right and Left alike — that frequently thrives at the polls. Today you may detect Peeperkorn-ish tendencies both in Brazil’s Lula and Argentina’s Milei. If Trump looks almost too close a fit, then surely so was Biden.

Peeperkorn soon dies; his “staggering mystery” vanishes from the sanatorium. The “great petulance” of simmering rancour and suspicion takes its place. A delicate dialectical balance dissolves like the valley’s snows in spring. Rivalry turns into hatred. The duel beside a frozen waterfall ends in symbolic fates for both parties. True to his values, Settembrini altruistically fires into the air. Naphta, whose voluptuous radicalism has always danced over a pit of despair, shoots himself in the head. Within a few pages, we flash forward to a glimpse of Hans amid the mud and gore of the looming “worldwide festival of death”. Up on the Davos heights, the interminable but rule-governed wrestle among ideas and ideals may exhaust its combatants, and bewilder its witnesses. But the true threat to health — of the mind, and of society — will begin only when it stops.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe