A demonstrator protests the 2015 election result (David Cliff/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

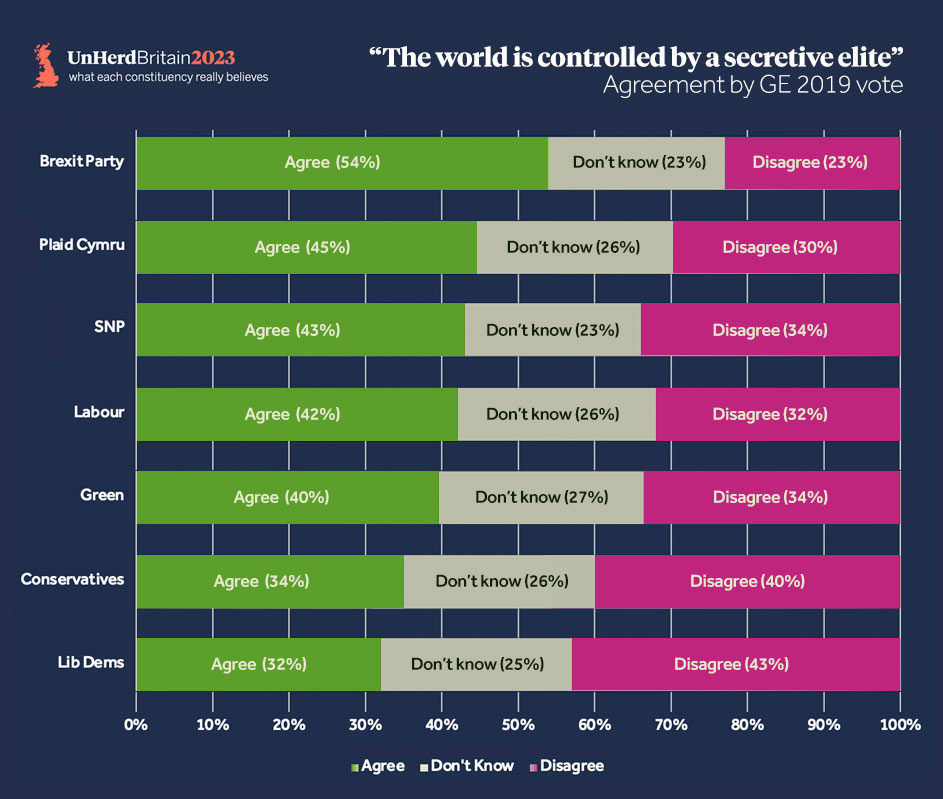

“The world is controlled by a secretive elite.” This claim will strike some as conspiratorial nonsense and others as an obvious statement of fact. Either way, it is now beyond doubt that a large minority of the adult population believes it to be true. The latest data from UnHerd Britain reveals that 38% of the British population agrees, while 33% disagree and 30% are not sure.

It is a useful phrase to measure core beliefs because it takes us beyond the idea of conspiracy theories, with all their distracting details and absurdity, to the underlying intuition that fuels them. In this world view, the “elites” are faraway and malevolent, exercising control in self-serving ways; meanwhile, democratic politics and the mainstream media are regarded as little more than distractions, likely in the service of powerful secret masters.

Whatever people believe about specific conspiracies — and this week offered no shortage of them, from UFOs over North America to hushed-up explosions in Ohio — our findings reveal how widespread the underlying mindset is that propels them. Thanks to our partner Focaldata and a statistical process called MRP, we can now see which constituencies are the most and least conspiratorial in the country. The results shed new light on how these voters should be viewed by the main political parties.

First, it is clear that conspiratorial thinking is not a “Right-wing” phenomenon. Voters who believe in a controlling secretive elite are much more likely to vote Labour than Conservative, and much more likely to live in a safe Labour constituency. By this measure, the 10 most conspiratorial constituencies in the country are all safe Labour seats, whereas the 10 least conspiratorial constituencies are all Tory (except Chesham and Amersham, which switched to Lib Dem in the 2021 by-election).

As the above table shows, the “most conspiratorial” list is made up of poor and highly diverse inner-city constituencies, which may explain why people come to feel so alienated and suspicious. In these places, a conspiratorial world view is the norm — in Birmingham Ladywood, for example, only 14% of people disagree with the statement. Meanwhile, in the rolling Chiltern hills of Chesham and Amersham and the affluent enclaves of Henley and Mole Valley, where the elites likely seem less distant and more on your side, few are concerned. It is a useful reminder to politicians of all parties that, while they may find conspiratorial voters troublesome, many come from the most disadvantaged communities.

Second, the results should encourage new anti-establishment parties on both the Left and Right. Thanks to our unusually large sample size of more than 10,000 respondents, we were able to measure the attitudes of voters who chose even the smallest parties in 2019 with a high degree of confidence. More than any of the mainstream parties, including Labour, the voters most prone to a conspiratorial outlook come from the anti-establishment parties: 54% of Brexit Party voters agree with the statement, alongside 45% of Plaid Cymru voters and 43% of SNP voters. So, while the Brexit binary pushed a larger proportion of voters towards the two main parties in 2019, it seems there are millions of voters who remain potentially open to new populist appeals.

There is a specific lesson here for the Labour Party. When I first tested this phrase at YouGov during the Labour leadership election of 2015, the belief that “the world is controlled by a secretive elite” was revealed to be a defining characteristic of supporters of Jeremy Corbyn: 28% of Corbyn’s backers strongly agreed with it, compared to 16% of Yvette Cooper’s and just 7% of Liz Kendall’s. Today, 42% of Labour voters agree with it, of whom 18% strongly agree. Antisemitism may have finally been dealt with in the Labour Party, but the mindset that drove it has not disappeared.

This suggests that, rather than Brexit or the election of Trump, the shock outcome of the 2015 Labour leadership election was the first real marker of the new era of low-trust and high-volatility politics; and the best way to understand it is by looking at the general election that took place immediately before. Today, it seems almost comic to recall, in the context of the eye-watering sums borrowed by successive Conservative governments, that the 2015 election was dominated by technical discussions of exactly what percentage point of austerity was appropriate to cut the deficit. Tory strategist Lynton Crosby calculated — correctly, as it turned out — that if nothing more interesting were discussed, the Tories would win by default. It was a cynical way to treat an electorate, for which he was rewarded with a knighthood. Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls, meanwhile, frightened of seeming weak on economics, committed a Labour government to “austerity-lite”.

Come the election, the differences between the main parties were marginal; voters sensed a stitch-up in which the Tories and Labour had colluded to starve them of a more meaningful choice. It is hard to say they were wrong: 2015 saw the UK’s highest ever immigration numbers, for example, but this topic was hardly mentioned in the campaign. A rejection of this non-choice sowed the seeds not only for Corbyn’s election but for the Brexit result the following year.

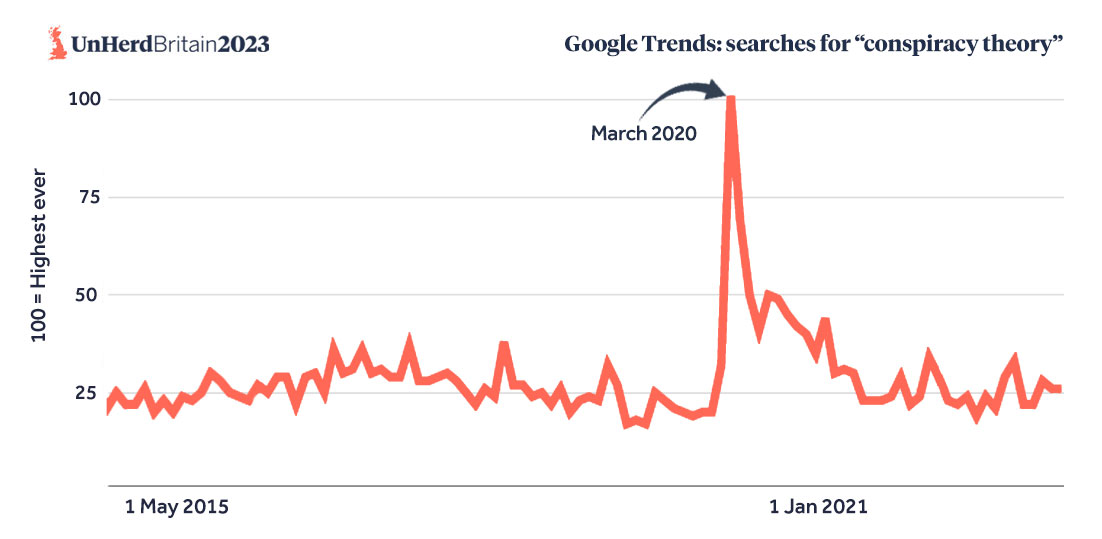

The story of what happened in the years since 2016 is well-known. First came the attempts to frustrate the Brexit vote, which confirmed voters’ worst suspicions about cross-party collusion and elite disregard for the democratic process. And then came the rolling Covid lockdowns, which in turn radicalised a whole new constituency. There has perhaps never been a policy so life-altering and so little-debated, with a cross-party consensus parroted throughout much of the media. In those dystopian months and years, millions of people lost trust in authorities and turned to alternative explanations. These were not Right-wing activists or spotty teenagers in basements: they were mothers, grandparents and people who had never before been political. It’s hardly surprising that Google recorded the all-time high of searches for “conspiracy theory” in March 2020.

The pattern, from the 2015 election through to the pandemic, is that whenever views are suppressed, distrust and alienation follow. It is when the “Overton Window” is too narrow, not too wide, that politics feels fake and conspiracies abound. The distrust that now cuts across society is not the fault of a few small-time cranks and bad-faith opportunists — it is overwhelmingly the creation of elites who consistently tried to deny the electorate real choices.

Fast forward to the past few months, with the ejection of Liz Truss as prime minister and the rehabilitation of pre-2015 figures such as Jeremy Hunt, and many will be hoping that the era of political turbulence is finally coming to an end. It certainly feels it; for the first time since 2015, there are two technocrats at the helm of Britain’s major political parties. Centrists in both parties are hoping that as Corbynism and Brexit recede into history, the “grown-ups” will be back in charge.

But today’s UnHerd Britain data suggests that, beneath the surface, voter distrust and suspicion are more present than ever; and that the currents that propelled both Jeremy Corbyn and Brexit still run right through Labour’s heartlands. If the 2024 election is anything like 2015 — with the mainstream parties becoming harder and harder to tell apart — it could be the beginning of a whole new wave of democratic revolts.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe