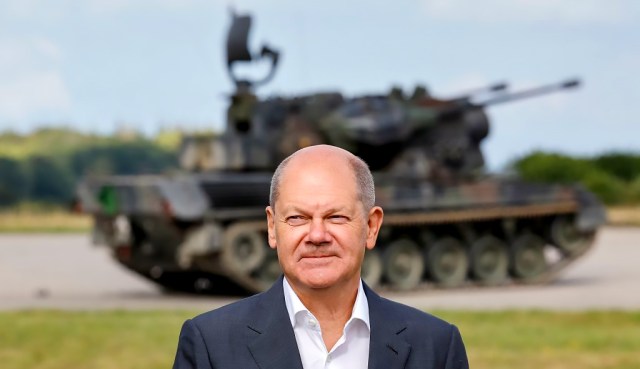

It’s behind you. Credit: AXEL HEIMKEN/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

It’s been nearly a year since the Chancellor of Germany stood before the Bundestag and gravely proclaimed a Zeitenwende, a tectonic shift in the nation’s defence policy. There would be a special fund of €100 billion to beef up the hopelessly under-equipped Bundeswehr, or armed forces. Olaf Scholz also promised to ramp up defence spending to 2% of GDP, in line with NATO rules (and, awkwardly, Donald Trump’s demands). Zeitenwende crucially, moreover, implied stepping up for Ukraine. But not much of that has happened since.

Today, around 50 defence ministers from around the world are meeting at the US air base in Ramstein, not far from Frankfurt, to again discuss western military support for Ukraine. Naturally, Germany will be in the spotlight. The US and other allies are counting on Scholz to take on more responsibility, to assume more leadership in Europe’s greatest security crisis in decades. And Scholz has been making the noises that Germany’s allies have hoped to hear: in a recent article in Foreign Affairs he writes: “Germans are intent on becoming the guarantor of European security that our allies expect us to be.” This echoes Scholz’s stated aim of making Germany a Führungsmacht, a leading power. But how close is he to achieving it? Very, very far.

The visiting defence ministers will encounter a Germany riddled with problems. For one, Monday saw the resignation of the incompetent defence minister, Christine Lambrecht. By Tuesday a new one, Boris Pistorius, had been named. He’s in for a baptism of fire. Germany has been under enormous pressure to supply the Leopard 2 battle tanks that Ukraine has been requesting for months — or at least to green light the re-export of the German-made fighting vehicles from countries like Poland and Finland. And that pressure was ramped up a notch this week by Britain’s decision to provide Challenger tanks.

In truth, there’s little willingness in Germany to spare any of the 340-odd Leopard 2s in use by the nation’s army. The government, on this front, has been dithering and stalling — or at least is that how it comes across publicly. Back in October, Scholz’ spin doctor Wolfgang Schmidt had all sorts of strange excuses not to provide the tanks. The Ukrainians wouldn’t be capable of maintaining the sophisticated German machines. Or, even weirder, the iron cross on the tanks would indicate to the Russians that the Germans were an active participant in the war. At which Ukrainians tweeted: “Don’t worry, we have paint.”

As with every German weapons delivery, making it happen would take a solid kick up the arse from President Joe Biden. Perhaps one was delivered in the phone call between the two men on Tuesday. But at the Davos summit the next day, Scholz’s communication on Ukraine was still vague and non-committal. When asked about the Leopards, he dodged the question and rattled off a list of armaments that Germany has delivered so far. It’s true that these armaments have not been insignificant. They have included howitzers, mobile anti-aircraft guns and surface-to-air missile systems. This month, the German government pledged 40 Marder infantry fighting vehicles — but only after dragging its feet for months.

Why isn’t the Zeitenwende happening a little quicker? Partly because Germany’s military structures are sclerotic. Modernising them must be the eternal quest of the nation’s defence minister. Especially bureaucratic is the procurement of weapons and gear. A small example: a pedantic military official once noticed, while purchasing tanks, that they didn’t have mirrors that conformed to the German highway code — so he or she absolutely insisted on getting them installed, complicating and slowing down the acquisition.

Ursula von der Leyen, while serving as Angela Merkel’s defence minister, hired McKinsey to sort out the Bundeswehr’s crusty organisational structures. A consulting budget of €2.5 million ballooned into €100 million, in what was known as the “consultant affair”. Relevant data requested by a parliamentary enquiry vanished under von der Leyen’s watch — but none of the allegations stuck. And although she massively boosted defence spending, the operational problems persisted.

Even more useless was Lambrecht, who took the reins of the defence ministry in December 2021, when Olaf Scholz’s coalition assumed power. In response to the Russian invasion a few months later, she dispatched 5,000 helmets to Ukraine, earning her ridicule. But her true talent was social media blunders, which included a post of her son riding in a military helicopter, and a New Year’s Eve video message with a backdrop of exploding pyrotechnics that sounded a lot like artillery fire. Empathy wasn’t her strength. Neither was running the military. She achieved practically nothing with a budget of €100 billion. Last month, all 18 Puma armed personnel carriers participating in an exercise broke down, coming to symbolise how ill-prepared the German army is for combat.

Lambrecht’s replacement, Boris Pistorius, is said to be a tough-talking, no-nonsense kind of guy. His appointment has upset the gender parity of the Scholz cabinet, attracting criticism from the Left. But hiring a capable minister should probably take precedent at this point. There’s a war out there — and the double challenge of getting Ukraine what it needs and turning the German army into an effective defence force once more is enormous to say the least.

But it’s not just practical challenges slowing down the tectonic shift. Equally complex are the beliefs that inform the German approach to Ukraine. Pro-Russian and anti-American impulses are common on the political fringes, among both the far-Right AfD and far-Left Die Linke, but also among mainstream politicians, including Michael Kretschmer, the premier of the eastern state of Saxony. This is the same Michael Kretschmer who called for the repair of the Nord Stream 1 undersea pipeline that was attacked in September. We’ll need that cheap Russian gas after the war, Kretschmer said. Granted, his state has close business links to Russia, but isn’t it a little early to start cozying up to the aggressor?

As I’ve written for UnHerd, many East Germans feel less connected to “The West” as an idea. It’s common in this region to reject military support for Ukraine and believe in a negotiated peace with Putin. Which is confounding when you remember that East Germans staged a peaceful revolution to free themselves from the Soviet bloc. That Ukrainians were also part of that bloc doesn’t seem to make East Germans more sympathetic to their resistance.

How influenced is Scholz by such sentiments? None of the parties in his coalition are anti-western, per se. But last summer, Scholz’ foreign policy adviser Jens Plötner snapped dismissively: “You can fill many newspaper pages with 20 Marders [the fighting vehicles Germany would pledge to Ukraine], but larger articles about our future relationship with Russia are less frequent. That question is at least as exciting and relevant.” Plötner has, for years, played a key role in Germany’s appeasement of Russia. His comments came not long after the discovery of mass graves in Bucha.

It’s not so much what Germany does as how, according to Benjamin Tallis, senior fellow at the German Council for Foreign Relations, and author of the new book To Ukraine with love: Essays on Russia’s war and Europe’s future. For him, Germany is “moving at the speed of shame. It’s been pressured into taking every one of its steps to support Ukraine. Its leadership, particularly in the chancellery, has seemed extremely reluctant to take each one of those steps, or even providing weapons at all. Now we see it again on the Leopards, the main battle tanks that would really be a game changer.”

To Tallis, the German approach is “a nostalgic politics for the recent past”, when Germany outsourced “its energy needs to Russia, its security needs to the US and its trade to China”. Since the defeat of Nazi Germany, West Germany has taken an ever more pacifist approach to foreign policy. In the late Sixties there was Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik, which allowed the Federal Republic to begin importing natural gas from the Soviet Union. And then came 1989.

As Thomas Bagger, currently Germany’s ambassador to Poland, articulates in his 2019 essay “The world according to Germany: Reassessing 1989”, in the decades following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany — more than any other country — took Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” to heart. Or, at least, an oversimplified version of Fukuyama’s thesis. Liberal democracy embedded in a rules-based international order was, in Germany, the only model with any future. Authoritarian powers like Russia and China could be turned into friendly, liberal partners if only you did enough business with them.

“Even long after it was clear that wasn’t going to happen, they continued to pursue this,” says Tallis. “It was remarkably comfortable, remarkably easy. You got to pretend you were doing good by doing well.” And all the while you whittle down your armed forces from nearly 500,000 troops in the Eighties to 180,000 today (a mere 24,000 of them combat-ready soldiers). You retire most of your military hardware, kick back and enjoy the peace dividend, under the umbrella of continued American protection.

The chickens have come home to roost, thanks to the war. Or, as Tallis puts it: “The hypocrisy of Germany’s position is coming out now.” Its recent history shaped by the idea that “Germans, having atoned for their past, had moved beyond these very 20th century vices of war, violence and power politics”, the nation has fallen foul of a “head-in-the-sand approach: We can get away with this while others sully their hands.”

One German commentator describes the lingering recalcitrance this way: “It sometimes seems like there’s been an accident, someone is injured, and there’s a bunch of people standing around. And Germany thinks, hopefully someone knows what they’re doing and takes decisive action to help the person, otherwise they might die. There’s a war in Europe, it would be good if someone did something. But Zeitenwende means we’re the ones who have to do something.”

Germany is doing something. The question is: is it enough? Despite the words coming out of Scholz’s mouth, it still feels as though the nation is in denial about the fact that there’s a devastating war raging just two countries away. Or it is, at least, in denial about the nature of that war — and the huge geopolitical shift it represents. Perhaps today, faced with so many of the world’s defence ministers, the nation will pull its head out the sand.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe