“The Trinidad-ISIS connection is not nonsense" (Al Jazeera)

Separated by 6,000-odd miles and myriad cultural differences, Syria’s killing fields and the sun and soca-drenched beaches of Trinidad and Tobago seem, on the face of it, to be worlds apart. While Assad’s war-torn country has been crippled by a decade of civil conflict, Trinidad, compared with most of its Caribbean neighbours, is still reaping the benefits of its early-Eighties oil and natural gas boom.

But despite the obvious differences between a failed Arab state of 18 million and a dual-island nation of 1.3 million, the two countries have become strange bedfellows. As unlikely as it may seem, Trinidad has become one of the world’s key recruiting grounds for Isis, a status linked to the country’s other big wheeze: drug trafficking.

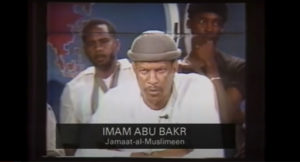

I was reminded of the connection between the Caribbean, the caliphate and cocaine last week after hearing of the death of 80-year-old Yasin Abu Bakr, an imposing 6ft 6in former TV producer and ex-cop who, as leader of the Jamaat al Muslimeen movement, in 1990 pulled off an attempted coup in Trinidad. For the better part of a week, Abu Bakr was effectively the head of state, making him the only person to ever lead an Islamic coup in the Western Hemisphere.

I met Abu Bakr in Port of Spain, Trinidad’s capital, in 2018 while researching a book on tribalism. Initially, I was drawn to him after more than 100 Trinidadians left home to join Isis and the jihadi cause, lured by a mix of fundamentalist ideology, warped romanticism and, in many cases, money. These young men travelled not just to Syria but also Iraq, often taking with them, and usually against their will, scores of women and children.

Given its small population, Trinidad has provided disproportionate numbers of jihadis to the ISIS cause. The US and Canada, with a combined population of some 350 million, larger Muslim communities and a seemingly more fertile breeding ground for anti-Western sentiment, are believed to have exported just 300 or so men and women to the Levant for jihad.

Yet in Trinidad, just 6% of the population are Muslim, and, of these, an estimated 90% are of Indian descent. While most are arguably “moderate”, a small minority has no strong attachment to their communities — thanks to a combination of atomised families, absent fathers, rampant drug addiction, gang culture and social marginalisation. Such a perfect storm feeds the worst excesses of identity politics, making young, impressionable and often desperate men vulnerable to the chest-beating Isis propaganda machine.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThanks, Mr Matthews. Years ago, Theodore Dalrymple noted another aspect of this problem in his enthralling essay “When Islam breaks down”. As a prison doctor, he had a ringside view of the UK drugs trade and its relation to disgruntled young men. The local Sikhs and Hindus were almost entirely absent from both the drugs trade and Her Majesty’s Prisons. Many prisoners were lapsed Muslims, except for their attitudes to women.

And recruitment of alienated young men to the Religion of Peace thrived. It gave young criminals the kudos of religious transformation and a sign of rebellion against the society which had wronged them. And halal food was better than prison grub – quite an incentive if you face years on a prison diet.

Dalrymple noticed that one grim feature of Islam: there is always someone less holy than you in observing Sharia Law. Thus, as in Trinidad, you have a divine excuse for killing a rival criminal.

Why did Singapore become Singapore, and Trinidad, Trinidad? Is it down to the personality types of those interested in governing? Is Port Of Spain no different really from any Venezuelan city of comparable size?

Principally because the Westminster model of government ensure racial divide between the two parties supported by respectively Afro Trinidadian and Indo Trinidadian populations. The constitutional arrangement results in the worst of patronage of each party’s supporters aided by the petroleum bonanza of recent decades. The mixed race and professional class 15% are effectively disenfranchised. The politicians dare not tackle the corruption reported on fairly by David Matthews. Right now, today, the Police Service is leaderless as the former Commissioner has been fired and the supposedly independent Police Service Commission members all resigned.

I am a National amd resident of TT of European descent.

There is cause for hope in this article. Imam Abu Bakr is dead, and hopefully other nutters will continue to kill each other wherever they are found, Trinidad, North America, Syria.

But if one is honest, it is the war on drugs that provides at least some of the oxygen to these movements. When we in the West declare victory in the war on drugs and legalise ALL drugs, regulate and tax them, is there a chance to stop the insanity.

Please note that this is not the same as saying that drugs are good, and I am not encouraging your third grader to smoke crack. I’m a veteran of the war on drugs, prosecutor in NYC during the Golden Age of Crack. This did no good, and I regret my time in this moronic and evil effort.

So why is the middle guy in the top picture holding his finger pointed down? It is not laying across the trigger guard as a military trained way.

Prislam, NIFP

What school of Imam do they have in Trinidad? Are they funded by KSA as the British Deobandi ones are? I would guess there must be some Salafist thing happening there, like

“The National Islamic Prison Foundation (NIPF) was specifically organized to convert American inmates to Wahhabism.”

NIPF is Saudi financed I read

It is an odd world, the way powers are spread about. IS formed in the Military Prisons of Iraq where the US Guards basically let the prisoners self manage if it means they self policed and kept order. Naturally a Salifist order formed and took the control, and thus ISIS. I have told of the ISI coupled with KSA Salifsm created the Taliban in the Madrassas of the Western Frontier.

I hear Saudi is now on a track to become another Dubai, fast changing as it sees the reality one assumes, and the Suudi elites do love their Luxury, and talk is of the half Trillion $ city they plan to build, Nuclear power I would guess, zero carbon… Jim Rodgers, the old partner of Soros who with him ‘Broke the Bank of England’ and invests around the globe says Saudi is the next place to invest….

“The Line is envisioned as the first outpost of Neom, a $500 billion 10,000-square-mile city-state being developed in Saudi Arabia’s Tabuk province near the borders it shares with Jordan and Egypt. (Neom is a portmanteau of the Greek word neos, or “new,” and mustaqbal, Arabic for “future.”)”

So what will all this mean for Saudi’s wish to export Jihad? My guess is they are moving on from that, but actually am just guessing – If a super modern, luxury city/state in KSA is to be called NewFuture.

Gosh, what a mess. Bring back the Empire!