The Tories won huge numbers of Remain voters (Photo by DANIEL SORABJI/AFP via Getty Images)

John McDonnell, in the election post-mortem, told Andrew Neil that this was a Brexit election. Once Brexit was laid to rest, he reasoned, the party could move ahead with its popular ideas. No need for a rethink.

Yet Labour won just 47% of the Remain vote, while the Conservatives captured 73% of Leavers. The Tories retained two-thirds of their 2017 Remain voters while Labour kept only half their Leavers. This is the story of the 2019 election, and it speaks to Labour’s deep misalignment with the cultural mood of the country.

And a deep dive into British public opinion shows that Labour Remainers, the group which dominates among party activists, sit well to the Left of LibDem Remainers on economics and are far too Left-liberal on culture for Tory Remainers and ex-Labour Leavers. This means the party either has to shift to the Blairite Right on the economy or tack in a conservative direction to woo Labour Leavers — much like the Danish Social Democrats.

To understand why, let’s focus on the relatively understudied Remainers, who tend to be typecast as one-dimensional metropolitan liberals. Yet Remainers are not all liberals. In fact, Tory Remainers are more similar to Labour Leavers on cultural issues than Remainers who voted Labour or Lib Dem.

Using 2017 data (which won’t differ much from today), Figure 1 shows that when it comes to beliefs about black, gay and female equality, Tory Remainers are closer to Tory Leavers than Labour Remainers.

Scale runs from 1 — not far enough — to 5 — gone too far

Figure 2 shows a similar story on immigration attitudes, with Tory Remainers twice as restrictionist as Labour Remainers (based on 2019 attitudes and 2017 vote). In a survey I conducted with Simon Hix and Thomas Leeper of the London School of Economics in 2017, we found that the average Tory Remainer was willing to admit 61,000 people from the EU per year compared with 78,000 for Labour Remainers. For Asian, African and Middle Eastern immigration, the numbers were just 47,000 for Tory Remainers versus 65,000 for Labour Remainers.

We find something similar on both English and British national identity in the 2017 British Election Study, with Tory Remainers considerably closer to the nationalistic Labour Leavers than the more cosmopolitan Labour Remainers. There is also an important difference between Tory and Labour Remainers in their affection toward the European institutions, as figure 3 reveals. In other words, for Conservative Remainers, a Remain vote was a pragmatic rather than expressive choice.

In effect, there are three groups of Remainers: conservative, liberal and Left. Whereas working-class Leavers are cross-pressured by economic factors, inclining some toward Labour, many Remainers are cross-pressured by both economic and social conservatism toward the Tories. This gives the Conservatives an advantage, which showed up in their 2019 result, where they won two-thirds of 2017 Tory Remainers.

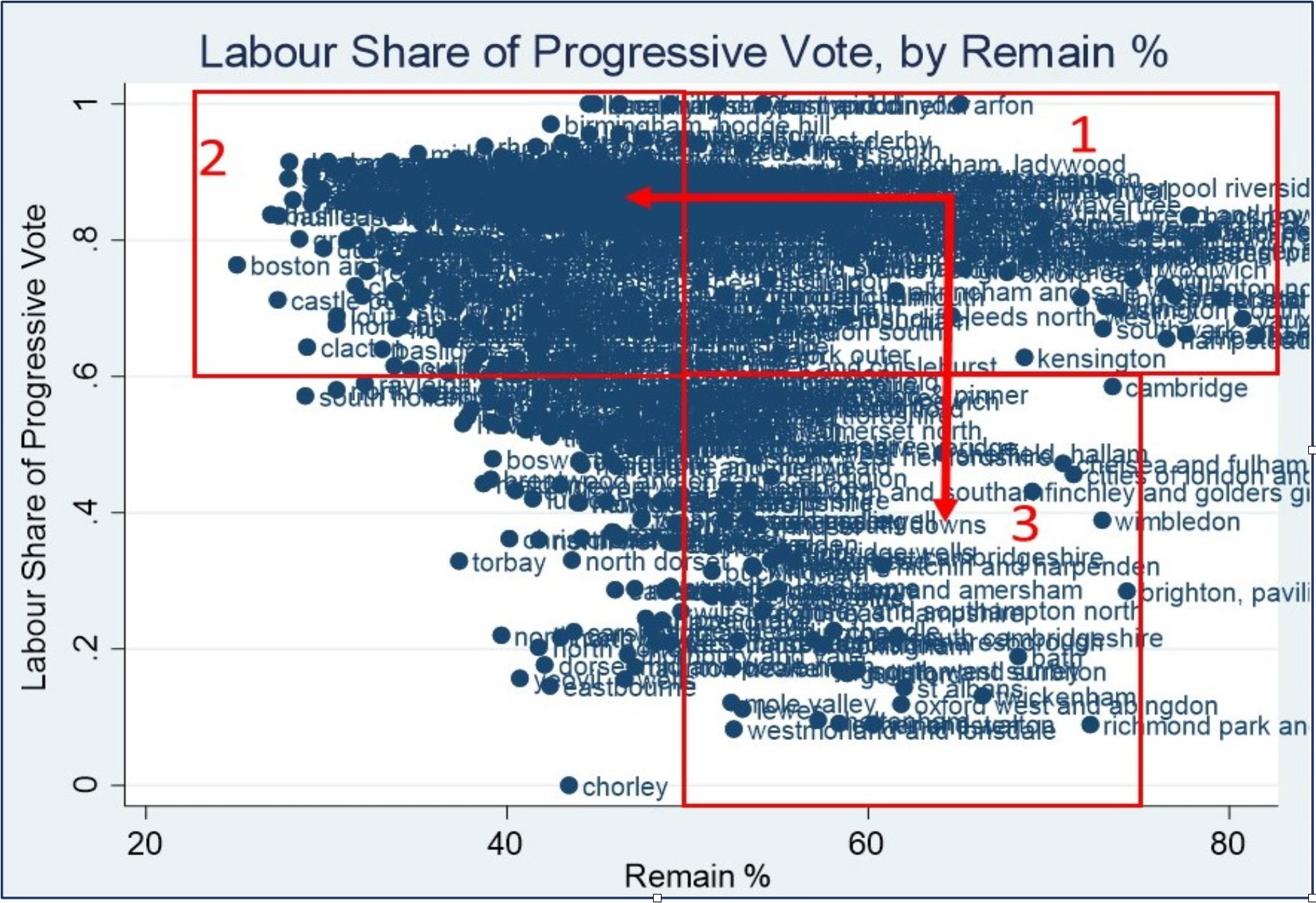

A good barometer of how well each party is doing against its pool of ideologically-aligned voters is to examine the share of the progressive vote won by Labour and compare it with the proportion of the Right-wing vote won by the Tories. Whereas the Tories consolidated the vast majority of Right votes, losing little to the Brexit Party, Labour bled a considerable share of progressive voters to the Lib Dems and Greens, often in battleground constituencies.

Figure 4 shows that in Leave seats (at top left of chart), Labour won most of the progressive vote. The problem is that Leave seats are slanted against Labour, making them difficult to win. In more Remain constituencies, the vote was bifurcated into a Left-Remain and liberal-Remain zones, dissipating Labour’s advantage.

Figure 4.

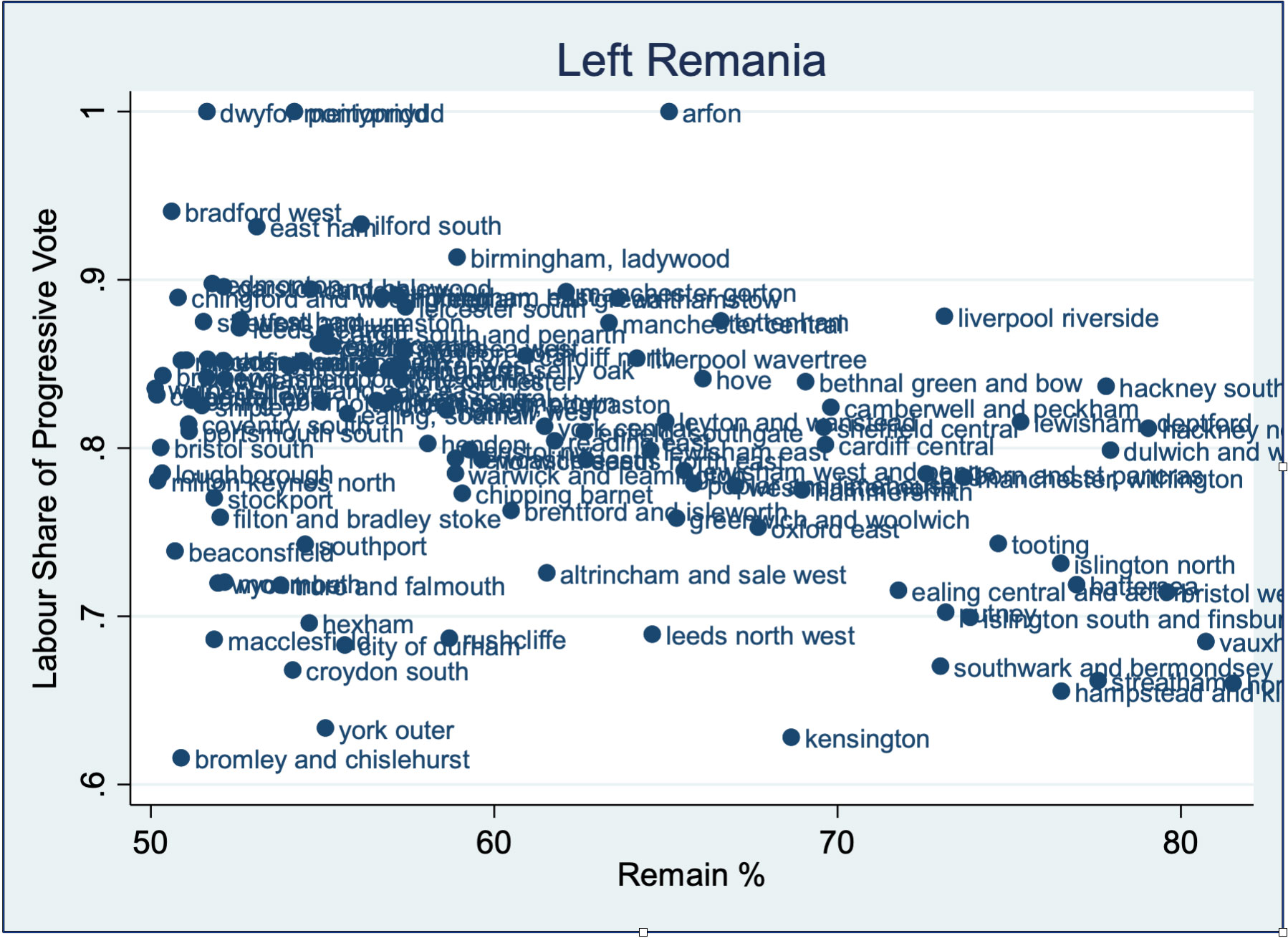

Essentially, Labour needs to appeal to voters in two or three of the zones. The comfort zone of the party is zone 1, populated by culturally and economically Left voters, concentrated in inner cities and university towns, with their young, highly-educated and ethnically diverse populations. I call this “Left Remania” in figure 5.

Figure 5.

In order to expand, the party first must make inroads into zone 3, Liberal Remania. This is depicted in figure 6: a Remain-voting region where the Labour share of the progressive vote is below 50%. On the British Election Study, 2015, Lib Dem voters were a full scale point to the right on economic redistribution from Labour voters. Labour averaged 2 out of 10, the Lib Dems 3 and Tories 4.5. Thus moving into zone 3 will require a softening of Corbyn-McDonell economic redistributionism and a corresponding effort to instil greater confidence in Labour’s stewardship of the economy. While this wouldn’t get Labour all the way to 325, it would be an important start.

Figure 6.

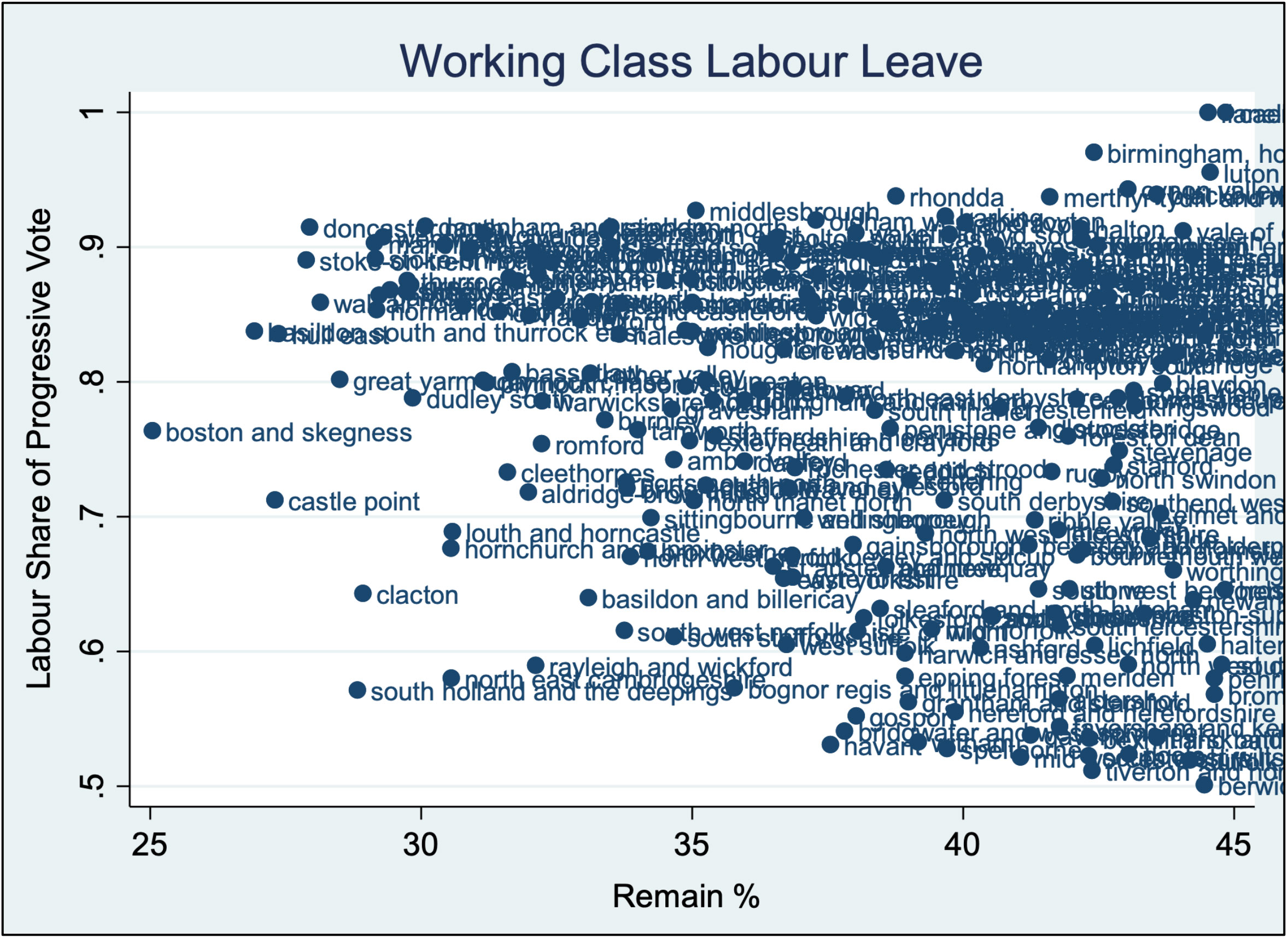

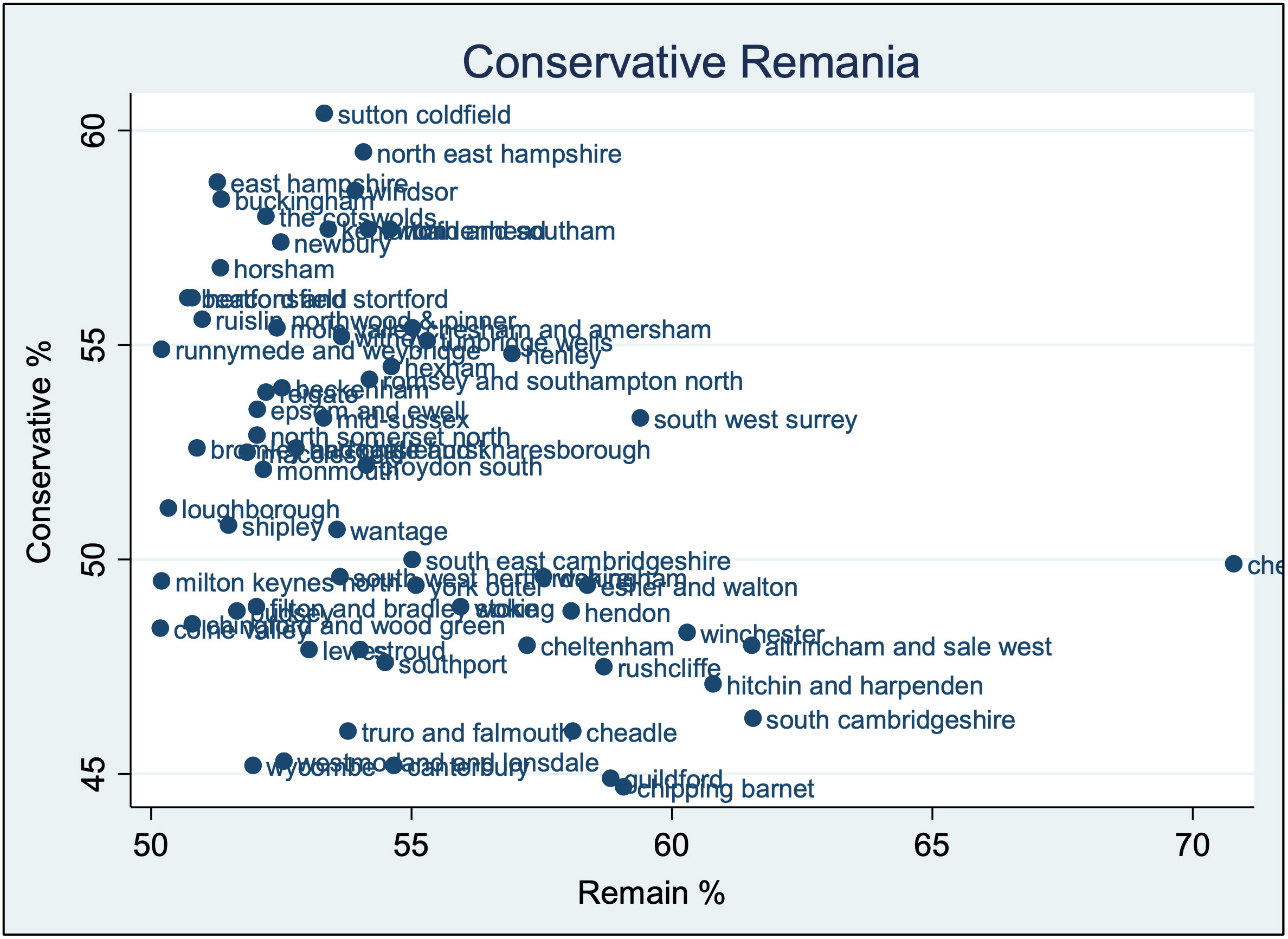

In order to move closer to 325, Labour also has to moderate on culture, stepping back from overreach on questions of immigration and the race-gender-sexuality agenda. They must find a way to either recapture the culturally-conservative working-class Leavers in figure 7 or appeal to successful suburban and provincial Tory Remainers in figure 8.

Figure 7.

Both present formidable obstacles. Working-class Leavers are further from Labour culturally, but, as we saw, Tory Remainers are both economically and culturally estranged from the median Labour Remainer.

Figure 8.

The notion that Labour can remain wedded to its Momentum agenda, combining a far-left economic and cultural progressivism, and simultaneously win a majority, is a pipe dream. Assuming Labour sticks to its economic programme due to its allergy to Blairism, it will need to take on its cultural radicals and rediscover national protection. As I note elsewhere, this is not going to change after Brexit. Post-Brexit, issues such as immigration, national identity and identity politics will, if anything, gain in salience.

Labour is on the wrong side of where it needs to be to win crucial voting blocs outside its comfort zone. In order to succeed, it must become more like the Danish Social Democrats, engaging in a cultural revolution akin to the economic one Tony Blair pioneered in the mid-90s.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe