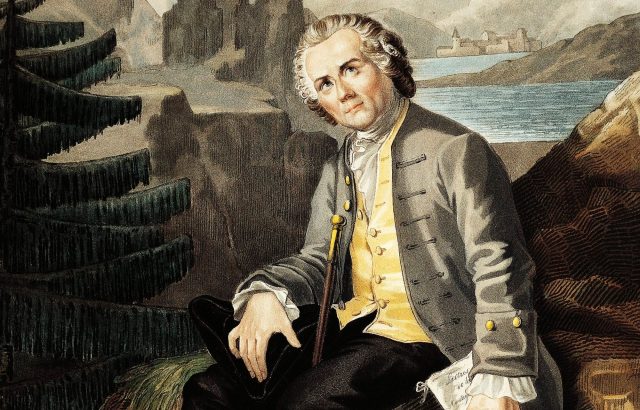

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, rolling his eyes at the UK’s failed attempt at democracy. Credit: DEA / G. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini via Getty Images

When the bestselling Swiss writer Jean-Jacques Rousseau arrived in Britain in 1766 as an exile from persecution he was a very desperate man. He must have been, since he was a committed Anglophobe, and as it was he stayed for just over a year in perfidious Albion before deciding to take his chances on the continent. So much for gratitude.

Rousseau, one of the most famous public moralists in Europe, was contemptuous of the idea that Britain is a democracy. “The people of England regards itself as free,” he wrote, “but it is grossly mistaken; it is free only during the election of members of parliament. As soon as they are elected, slavery overtakes it, and it is nothing.”

The philosopher was born and raised as a citizen of Geneva, then a small, independent city-state with a long tradition of direct democracy. That is what the word democracy meant at the time – the idea of a representative democracy, where voters elect people to govern on their behalf, was seen as a contradiction in terms, and not just by Rousseau. If he were alive today he would not recognise any states as democratic in his sense, since all that call themselves by that name are in fact ruled by elected elites, not by the people. They are really oligarchies — rule by the few — politely disguised as so-called “representative democracies”.

Although Rousseau was not the first person to champion popular sovereignty, he has always been its most potent and persuasive advocate. That is why his famous political work, The Social Contract, has been continuously in print since it was first published two and a half centuries ago, a political classic still read by thousands of people across the world every year. It sets out the case for popular rule more powerfully than any book ever written, which makes it a key text for our own time. It is more timely now than either Marx’s Communist Manifesto or John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, which is not to deny their own importance and relevance.

Rousseau believed that the ‘general will’ of the people is the only legitimate basis for political rule, a very radical idea in the 1760s and one that has inspired generations of revolutionaries and populists ever since. The leaders of the French Revolution held Rousseau in the highest esteem, much as Lenin regarded Marx, which is why some of the bloody excesses of that event tarnished his reputation, even though the Rousseau had died a decade earlier. The reference to the law as an expression of the general will (volonté générale) in the 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was almost certainly directly inspired by Rousseau. It represents a radical transformation in the foundations of legitimate government.

The Founding Fathers of the US, by contrast, were not impressed by his ideas, since they feared mob rule and the tyranny of the majority as much as royal despotism. This is why they designed a complicated political system that was deliberately weak and full of checks on the popular will, such as the Electoral College, the Bill of Rights, and the Supreme Court, as bulwarks against democratic despotism. They deliberately founded a republic, not a democracy, a word that nowhere appears in the American constitution.

The form of democracy that Rousseau advocated was not liberal. His political models were in the ancient world (above all Sparta and Republican Rome) and in modern, Calvinist Geneva. He argued that democracy could not function unless its citizens truly cared about the public good above their own private good. They must be public-spirited citizens before they are self-interested individuals. The best way to achieve this, he thought, is by an intense civic pride that overcomes our natural selfishness and strengthens the bonds of citizenship. “Do we want peoples to be virtuous?” he asked. “Let us then start by making them love their country.” That is why many 20th century liberals have condemned Rousseau as a “totalitarian democrat”.

But not everyone who rejects the liberal, representative form of democracy is necessarily a totalitarian. Rousseau is better understood as a precursor of what is now called “national populism” (a term recently coined by the political scientists Matthew Goodwin and Roger Eatwell). He saw a basic incompatibility between liberalism and democracy and took his stand with the latter.

Rousseau was from a modest family of provincial craftsmen who came to see his age as deeply corrupt, divided and unjust. He is the eloquent voice of those who feel alienated, disempowered and ignored by the rich and powerful who dominate politics and benefit most from a system of government that was originally meant to be “of the people, by the people, for the people”, grievances that sound very familiar to our ears today. Rousseau’s faith was in the simple virtues and humility of ordinary citizens, which he contrasted with the decadence and arrogance of the elites who ruled pre-revolutionary France.

The compound “liberal democracy” is coming apart in our time, as Rousseau would have predicted it must, a victim of its own inherent contradictions. The recent rise of populism is increasingly forcing a choice on us.

On one side, it has provoked many liberals to challenge policies they dislike in the courts and to sharpen their attacks on more direct forms of democracy (such as referendums and popular initiatives) in favour of diluted, representative forms, often in the name of the “sovereignty of Parliament”. They sound a lot like classical liberals of the 19th century such as Mill, who were uneasy with the rising power and assertiveness of ordinary citizens whose views and behaviour they perceived as a threat to the idea of man as a “progressive being” (in his words).

On the other side, many populists are now increasingly impatient with liberal, cosmopolitan values, which they view as the ideology of a privileged elite detached from the lives of ordinary citizens and disdainful of their views.

What seems new to us is really a resurgence of a debate that goes back to Rousseau’s time, before the 19th century foundation of liberal democracy, which has long been the established form of democratic rule in the West. We are moving from an age of “liberalism and democracy” to an age of “liberalism or democracy” again.

Nationalist democratic politicians who are openly critical of liberal pluralism, such as Vladimir Putin, Viktor Orbán and Jair Bolsonaro, are increasingly common now, even in western Europe, although not yet dominant there. They see liberalism as weakening democratic solidarity and identity, whereas liberal democratic leaders, such as Angela Merkel, Justin Trudeau and Emmanuel Macron, see liberalism as essential to democracy. Challenges to the liberal conception of democracy are likely to grow, echoing the language and ideas of Rousseau.

As the old and increasingly obsolete political ideologies of Left and Right that emerged in the wake of the American and French revolutions over two centuries ago give way to a new axis of political debate around globalism and elitism on the one hand, and populism and nationalism on the other, Rousseau’s relevance and importance is bound to grow even more. Rousseau, the prophet of populism, is a thinker whose time has come again, for better or for worse.

How To Think Politically: Sages, Scholars and Statesmen Whose Ideas Have Shaped the World, by Graeme Garrard and James Bernard Murphy, is published on 8th August (Bloomsbury, £14.99)

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe