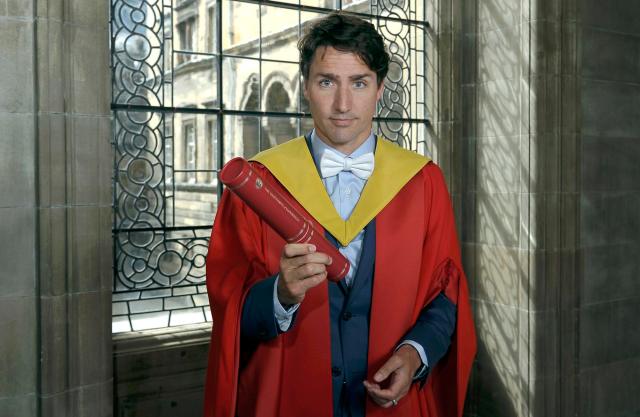

Putin is not going to be replaced by a Justin Trudeau-like figure with a Harvard degree in economics. Credit: Neil Hanna – Getty

If John Stuart Mill’s ideal system of government had been in place at the last general election, a Corbyn government would now be in power in Britain. Like many rattled liberals today, Mill feared rule by the ignorant masses. What we now call ‘populism’ was not an aberration, but a permanent danger of democracy. Superior knowledge and intelligence had to be recognised in a liberal state.

To this end, Mill proposed a system of plural voting in which graduates would have more votes than the one granted to ordinary citizens. As he framed his proposal in Considerations on Representative Government (1861):

“All graduates of universities, all persons who have passed creditably through the higher schools, all members of the liberal professions, and perhaps some others should be registered, and allowed to give their votes as such in any constituency in which they chose to register: retaining, in addition, their votes as simple citizens in the localities in which they reside.”

Mill’s proposal reflected his belief in the advance of human knowledge. He looked forward to an ‘Exact Science of Human Nature’, which would formulate laws of psychology and society as precise and universal as those of the physical sciences. With the development of Utilitarianism, morality was itself becoming a science. In future, ethics and politics would not be ruled by the primitive intuitions of uneducated people. Decisions would be made on the basis of the expert judgment of people trained in the social sciences. This was the path to progress.

Mill has had a good press lately. The Economist has presented him as a classical liberal who can serve as a guide to the perplexed in a time of liberal confusion. Many who have been alarmed by practices such as de-platforming have urged that we revisit his celebrated defence of free expression in On Liberty.

Here at UnHerd, Victoria Bateman has argued that Mill is “a thinker for our times”, who could help create a freer and fairer type of capitalism. If we returned to Mill’s verities, liberals would have a firmer grip on their values and a shaky liberal order could be set back in place.

Corbyn’s near-victory last June is an ironic commentary on these hopes. The university graduates whose enhanced influence Mill believed was so essential to human progress were crucial in bringing the Labour leader to the brink of power. A major factor was Labour’s offer to abolish student tuition fees. But graduate support for Corbyn extended well beyond those that would benefit from this policy.

The Remainer internationalism that the party seemed to embrace during the campaign (while officially endorsing Leave in its election manifesto) chimed with a progressive consensus taught in universities for decades. Like Mill, millions of graduates believe liberal values are gradually unfolding in the course of history. Labour managed to project itself as the embodiment of these values.

The ironies here are multiple. If Labour had won, it would have presided over an eclipse of liberal values. Equipped with the resources of British state, the alt-Left party Corbyn has created would have been in a position to condone antisemitic racism and endorse terrorist movements. At the same time, the erosion of freedom of expression in universities would intensify. The progressive consensus would become immovably entrenched. Soon the contestation of received truths Mill celebrated would be barely a memory.

At this point, a fork in Mill’s liberalism becomes visible. If only one set of values can be grounded in science, why allow others to be promoted in centres of learning? There can be little reason for giving anyone who rejects scientifically established truth equal freedom to speak or shape collective decisions. In effect, this was the rationale of Mill’s proposal for plural voting. But if those who base their values in a science of society are given overriding weight and influence, the result will be intellectual uniformity of the kind Mill attacked in On Liberty.

In fact, Mill’s science of society was nothing of the sort. He aimed to formulate laws as exact as those in the natural sciences, and as powerfully predictive. Yet he was unable to identify a single one of these laws and anticipated none of the great upheavals that were to come. Not only did he fail to anticipate the rise of 20th-century totalitarian movements, such as Nazism and communism, but 21st-century illiberalism was beyond his imagination. The worst he could imagine was that progress would stall and what in On Liberty he called “Chinese stationariness” – intellectual and social stagnation – would settle on Europe. The rise of an innovative and authoritarian China was inconceivable to him.

Mill never doubted that a universal civilisation grounded in liberal values was the eventual destination of all of humankind. With a few perfunctory reservations, this remains liberal orthodoxy today. The empirical basis of this orthodoxy is slight. Twenty-first-century liberals claim to base their values on observation and experience. Some, like Mill, have posited a science of society that supports these values.

But there is nothing scientific in the belief that a liberal way of life that existed in parts of Europe and North America over the few past hundred years is set to spread throughout the world. If we rely on observable facts and trends, the likelihood must be that a liberal world order belongs in the past.

Writing in the introduction to On Liberty, Mill tells us that he grounds his argument for freedom not on “abstract right” but “utility – the ultimate appeal on all ethical questions; but it must be utility in the largest sense, grounded in the permanent interests of man as a progressive being”. What is “man”, though? Certainly not an empirically observable species.

All that can actually be observed is the miscellaneous human animal, with its many contending values and ways of life. Again, there are many understandings of progress. If Mill believed it meant increasing freedom and individuality, for the founder of modern utilitarian ethics, Jeremy Bentham, it meant maximising the satisfaction of wants. Mill spent much of his adult life vainly trying to reconcile the two.

Mill’s liberalism did not rest on experience or observation. Though he was not raised as a Christian – his father, a disciple of Bentham, made sure of that – Mill was like other Victorian thinkers in relying on ideas that make little sense outside of a theistic world-view. The belief that “man” is a collective agent working out its destiny in history is a relic of Christianity, unknown in polytheistic cultures and non-western religions such as Buddhism and Taoism.

The very idea that humans share a common historical destination is a remnant of monotheism. Reframing the universal clams of western religion, Mill’s secular liberalism – like his science of society – was not the result of any process of rational inquiry but an expression of faith.

Viewed historically, the liberal era was a moment in the aftermath of post-Reformation Christianity. If Europe had not been Christianised, it would most likely have been shaped by the polytheistic and mystery cults of the ancient world. Today it might resemble India. A universalistic, evangelising impulse would be weak or absent. Whether it would have been better or worse – or both – the West would not have produced political faiths like liberalism, that aim to project their values throughout the world.

Core liberal values, such as freedom of belief and expression, are by-products of early modern struggles within Christian monotheism. This fact could be passed over as long as successive versions of liberal values were underwritten by Western power. In Mill’s day they rested on European colonialism, and following the collapse of communism on the supposed triumph of free-market capitalism. The illusion persisted that the rise of liberalism revealed a universal law of human development.

In the event, a liberal world order has lasted only as long as Western hegemony. Today, non-Western powers are pursuing different paths of development, while much of the West has become the site of a paralysing culture war between hyper-liberal ideology and the forces of populism.

While Europe’s hegemony was lost as a result of the Great War, Western hegemony was reaffirmed in the American-led international system that was set in place after the Second World War. But it is a system that is palpably crumbling. If Russia is mocking and flouting the “rules-based order”, China is bent on reshaping it in its own image. India goes its own way.

Internally, Western societies are dismantling the liberties that were supposedly spreading throughout the world. Geopolitically, the West is heavily dependent on the authoritarian system that is under construction in China. Western commentators may complain about Xi Jinping’s surveillance state – a high-tech version of Bentham’s Panopticon, in which society was remodelled as an all-seeing prison – but not too loudly. The consequences of any serious upset or slowdown in China would be unfathomable. Any return of Chinese stationariness could be fatal to Western capitalism.

The time has passed when the West could dictate the terms of human development. Yet the delusion persists that the growth of wealth will give liberal values another lease on life. The sub-Marxian mantra that expanding middle classes will demand liberal freedoms as societies become richer is repeated endlessly in business gatherings and academic seminars.

No matter that Putin and Xi continue to be fêted by the middle classes in Russia and China, while in Europe they flock to Orbán and Salvini, Austria’s Sebastian Kurz and Jimmie Åkesson, leader of the Swedish Democrats. Never mind that that middle-class graduates are demanding that liberal freedoms be shut down in the institutions that once embodied them. Best not dwell on such facts, for they suggest that a liberal world order was an historical accident that cannot be repeated.

Classical liberalism – the default position of The Economist, along with The Wall Street Journal and The Financial Times – is a dead end. China is not going to become a liberal democracy, nor will it deviate from its market-Leninist economic system. Putin is not going to be replaced by a Justin Trudeau-like figure with a Harvard degree in economics. The far-Right will continue its advance across Europe for as long as key policies such as immigration remain removed from majority control. Whether or not he is re-elected, Trump marks an irreversible American retreat from the role of global backstop.

The combination of an intractably divided and fast-retreating America with an ascendant China means the post-war global settlement is history. Anyone who looks to classical liberal thinkers to deliver the West from its present difficulties is fixated on an irretrievable past.

It is possible to envision a stoical and realist liberalism that would accept that freedom and toleration must survive in a hostile or indifferent world. Liberalism would be recognised to be a particular form of life, like the others that humans have fashioned and then destroyed, but still worth defending as a civilised way in which humans can live together.

In practice a stance of this kind is hardly possible. Liberals cannot do without the faith that they form the vanguard of an advancing way of life. The appeal of John Stuart Mill is that he allows them to preserve this self-image, while the liberal world continues to evaporate around them.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe