Niall Carson/PA Archive/PA Images

Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair is no one’s idea of a populist. Indeed, he is so much a part of the global elite that he has spoken at the annual World Economic Forum meeting in Davos[1. Read this New York Times’ explainer on Davos from January last year – “How Davos Brings the Global Elite Together”] at least five times since 2005. If politics in the developed world is truly becoming less about left versus right and more about Ins versus Outs, Tony Blair is the Ins’ In.

So it is no surprise that the Tony Blair Institute released a report at the end of 2017 that was critical of the rise of populist parties throughout Europe. One can surmise Blair’s thoughts simply by reading the report’s subtitle: “Trends, Threats, and Future Prospects”. No surprise that the Duke of Davos’ non-profit sees populism as merely another Peasants’ Revolt.

The report is nevertheless required reading for anyone who seeks to understand the continued appeal of populist parties in the West. From start to finish, the report is an excellent summation of the ‘In’ perspective as it exists on the centre-left. It shows no understanding of why support for populist parties is on the upswing. Worse, the authors demonstrate no interest in even asking that question. This omission more than anything explains why populist sentiment is increasing, making a close examination of that blindness all the more compelling for those interested in reversing that trend.

Populism ill-defined – hence misunderstood

Populism is a hard thing to define. I defined it elsewhere as a “morality play in four acts” in which a leader mobilises discontented people under the banner of opposition to an “other”. An “other” being an implacable foe – whose rights must be removed for the people to recover their lost heritage. That “other” can be many things: an economic class or an identifiable minority, for example. The key element that distinguished dangerous populism from simply another mass and novel democratic movement, however, is the denial of political and or economic rights to the targeted “other”.

The Blair Institute report notes the importance of “the other” in populism but overlooks this key element. The report defines populism as a “claim to represent the true will of a unified people against domestic elites, foreign migrants, or ethnic, religious, or sexual minorities”[2. “European Populism: Trends, Threats, and Future Prospects”, p3]. It tries to distinguish this from normal political movements that “speak for the common man” by saying that only populists “explicitly define ‘the people’ against elites, immigrants, or some other minority, framing the interests of these groups as diametrically and inevitably opposed”.

But that cannot be the distinguishing feature of populism, as otherwise it would mean such accomplished leaders as the American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt were populists. FDR often decried his opponents as “economic royalists” who sought to end real democracy[3. See, for example, FDR’s speech accepting the Democratic Party’s nomination for the Presidency in 1936]. Defining populism in this way merely allows the authors to ascribe dangerous motives to what are mere political opponents. It is thus unsurprising that the authors examine “some of the harms populism is already inflicting on European politics” without even recognising the possibility that the rise of populist parties could be a normal reaction of a dissatisfied public.

Working class, nationalist populism is the Blair report’s real enemy

So, who are the Blair Institute’s political opponents? Despite mentioning that populism “can take root anywhere on the political spectrum, from the far-right to the far-left”, it – predictably – is those ostensibly found on the Right that come in for the most criticism.

Some of this is because, as the report notes, “right” populism has so far produced the most widespread political success. Seven Eastern European countries are run by parties the report characterises as right-wing populist. Three Scandinavian countries include populist parties in their governments, and the recent Austrian elections brought the “so-called Freedom Party” into government. “Left” populists are only in government in Greece and Lithuania, although the report overlooks the fact that Portugal’s ruling Socialists hold power only through confidence-and-supply agreements with the Left Bloc and with the Communist-led Unitary Democratic Coalition.

This omission, along with the pejorative characterisation of the Freedom Party, clearly betrays the report’s aim. Not all populists are created equal: those who prioritise restricting the number of refugees or migrants and question the increasing power of the EU come in for much more examination than those which merely campaign “against privatisation, national political elites, and European austerity politics”. Thus, political competition from right populists have “pushed many centre-right parties to adopt more extreme positions on issues including immigration,” and Austria’s and France’s chief centre-right parties “have embraced younger, more radical leaders”.

The report talks about the recent rise in the polls of the anti-immigrant Belgian party, Vlaams Belang, even though that rise merely recoups losses that party suffered in the last election, but never mentions the fastest growing party in Belgium, the far-left-populist Party of Labor. The rise of another far-left-populist, Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, is simply described in one sentence (without mentioning his name) as one way that “illustrate[s] the effect that populist parties can have on the mainstream.”

Blindness toward the Left; nostalgia for Cool Britannia

This blinkered view towards left-wing populism extends throughout the report:

- The name of Greece’s left-wing populist party, SYRIZA, is actually an acronym that stands for “Coalition of the Radical Left” but the report only mentions that SYRIZA could not govern on its own so it had to form a coalition with a non-left populist party, ANEL.

- Ireland’s Sinn Fein, descended from the anti-British, terrorist-sympathising group of the same name, is now the third largest party in Ireland, yet it is never mentioned once; other left-populist Irish parties, such as Solidarity-People Before Profit, also go unmentioned.

- Iceland’s new Prime Minister, Katrina Jakobsdottir is from the Left-Green Movement, a party formed by former leftists for whom the Social Democratic Alliance was too mainstream, but her ascension is passed over.

- And Germany’s left populist party, Die Linke – which literally translates as “the left” – is briefly referred to as “left-leaning”. The fact “the left” is labeled as “left-leaning” speaks volumes.

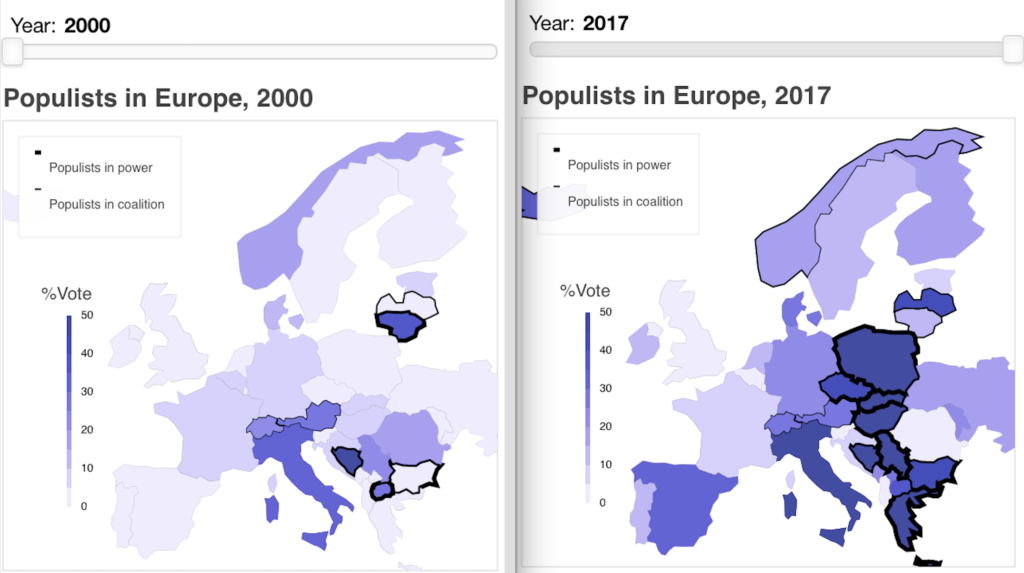

This tendency shows that the report’s real complaint is that Europeans are abandoning the globally-minded “Third Way” Blair did so much to pioneer as the UK’s prime minister. The report starts its charting of populism’s rise in 2000. In 2000, parties of the centre-left held the premiership in ten of 19 countries in European countries[4. The ten were the United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Portugal, Italy, and Greece. The three were Switzerland, Belgium, and France, where Lionel Jospin was Prime Minister and conservative Jacques Chirac was President. Social Democratic parties were the primary opposition in three other countries, Spain, Malta, and Austria. The left had been historically weak in the other three countries – Iceland, Ireland, and Luxembourg – and had almost never held the premiership in any of the nations.] that had never been part of the Warsaw Pact and were in coalition in three of the others. Market-friendy “Third Way” social democracy seemed to be the wave of the future.

Centre-left parties were also strong in the formerly Communist countries of Europe. They held the top job in five of the eighteen then-extant countries and were in coalition in three more[5. Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Kosovo, Albania, Ukraine, Montenegro, Bosnia, Macedonia, and Moldova. Social Democrats held the premiership in the Czech Republic, Croatia, Romania, Albania, and Montengro. It was in coalition in Bosnia, Bulgaria, and Estonia.]. Centre-left parties were the primary opposition in Poland and Hungary and would go on to win the next election in both nations. While historical reasons had prevented the emergence of a Western European style Left-Right axis in many nations, social democrats had established a strong foothold and successfully distanced themselves from the former Communists.

Today, the centre-left stands in ruins in most of Europe.

As Marcus Roberts noted last year, the centre-left is out of power in almost everywhere of note in Europe:

- It holds only four premierships in non-Warsaw Pact Europe and could lose two of those (Sweden and Italy) in elections this year.

- Traditionally strong centre-left parties posted among their lowest electoral showings in their history in elections last year in Austria, France, Germany, Norway, and the Netherlands.

- Polls currently show the Italian Democratic Party and the Swedish Social Democrats at their lowest shares of the vote ever going into elections this year.

- Only strongly anti-Blairite leftists such as Labour Jeremy Corbyn and Iceland’s Katrina Jakobsdottir have demonstrated electoral progress on the left in recent years.

Traditional centre-left parties are even weaker in former Warsaw Pact countries:

- Social Democrats in the Czech Republic and Hungary have been nearly wiped out, while Poland’s centre-left (the United Left Party) is no longer even represented in parliament.

- Centre-left parties are very junior coalition partners in only four former Warsaw Pact nations, serving under populist party prime ministers in three of those states.

- It holds the premiership only in Europe’s tiny southwestern periphery – Albania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, and Romania.

Why have populists displaced the centre-left? Blair’s report has no clue

What once seemed to be the wave of the future has instead been swept away by the tsunami of populism. One might expect a report from the Blair Institute to have been keenly interested understanding why this has happened. To the contrary. The report not only doesn’t answer this question, it never even tries to answer it. This fact more than anything else displays the insular thinking of the centre-left’s ‘In’-crowd – an elite so ensconced in an ivory tower of its own creation that it cannot even muster the curiosity to see what might exist beyond its walls.

Let’s think of what has happened since 2000 – the report’s benchmark date…

- China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, starting a rapid economic boom that has changed markets around the globe.

- Thirteen of the EU’s twenty-eight member states, and all of its post-Warsaw Pact members, joined the Union after 2000. These developments sparked rapid Western investment in many of these countries and enabled large numbers of Eastern Europeans to move to more developed countries in search of work.

Both of these factors are often cited by populist leaders in justifying their views on the EU, global trade, and migration, but the report fails to even mention that these acts might have contributed to the rising appeal of populism.

The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 is also, amazingly, never mentioned as a possible cause of populist appeal. Spain’s incumbent Socialist Party government was tossed out of office, leading to the rise of two populist parties – the centrist Ciudanos and the left-wing Podemos – who now hold the balance of power in that nation. The financial collapse clearly helped left-wing populism gain ground in Greece and Ireland, and the rise of UKIP and other anti-immigrant nationalists can be dated from the 2010 general election. Anger over the Greek bailout helped to drive populist party support in both Germany and Finland. Clearly the economic collapse hurt the less-skilled the most, yet again the report never considers that populism could be seen as a rational response to a crisis that was caused – in part – by the very global order championed by centre-left and centre-right establishment parties.

Opposition to increasing Muslim immigration is also a clear contributing factor to the rise of populism in many countries. Both the Sweden Democrats and the AfD rose rapidly in the polls after centre-right leaders allowed an unprecedented number of refugees from Islamic countries to enter. Some of the newer Eastern European populist parties, such as the Czech Republic’s SPD or Hungary’s Jobbik, also saw their support rise as the question of Islamic migration became more poignant. One can, as the Blair Institute does, support the idea of such migration but the report’s implicit contention that opposition to such migration is improper is itself perhaps an unexamined partial cause for populism’s appeal.

Corruption is also unmentioned by the report, a stunning omission given how many of the leading populist parties originated or rose in support to combat systemic self-dealing by the ‘In’s:

- Iceland’s governments have been regularly rocked by corruption scandals since the publication of the Panama Papers in 2016; three of the country’s eight current parliamentary parties did not even exist then.

- Italy’s 5 Star Movement, which leads the polls heading into Italy’s March 4 election, is primarily a movement for transparency and clean government.

- The Czech Republic’s ANO, the clear winner of last year’s elections, was started by billionaire Andrej Babis to combat insider corruption.

- Even the two populist parties most directly criticised for being undemocratic, Hungary’s Fidesz and Poland’s Law and Justice, came to power after secret tapes revealed a stunning degree of malfeasance by politicians from incumbent parties[6. Hungary experienced over a month of street protests in 2006 when Socialist Party Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsany was taped in a private speech saying his party had lied to win that year’s election and had done nothing in government to be proud of. Law & Justice came to power after a series of clandestine tapes made in an upscale Warsaw restaurant revealed cases of improper use of public power. See Politico and Washington Post.].

To overlook the role official corruption has played in stoking populism’s appeal is to overlook the degree to which the old centre-right/centre-left duopoly had grown distant from the people it purported to serve.

Nation states and democratic legitimacy

This latter point places the focus on the primary problem with the Blair Institute report. Democracy ultimately works when it serves the people to whom the government is responsible. European democracy has been founded on the concept of the nation-state for well over a century, starting at least no later than the drives of liberals to unite German and Italian-speaking nations into one state in the mid-19th Century. The Treaty of Versailles established the nation state principle as its lodestar in dismembering the multi-national Austro-Hungarian and Turkish empires. The post-Cold War break-ups of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia arose because linguistic nations within those multi-national states wanted their own nation states. This remains the aspiration of today’s leading separatist movements in Flanders, Catalonia, and Scotland.

Simply put, Europeans see themselves as citizens of their own nation states but not as citizens of Europe. As such, they still evaluate policy primarily through that lens rather than through the pan-global lens preferred by the Davos set. It is certainly true that global poverty is down dramatically in the last quarter-century, for example, but that fact does not motivate voting behavior in a citizenry whose primary question is “is it good for this nation?” Nor does the spread of prosperity to the former Warsaw Pact nations within the EU, whether through direct investment in those countries or through migration of their nationals to wealthier states, appeal to a large number of citizens in those states who have seen their life prospects diminish over the past decade and a half.

The report’s authors choose not to see this. Instead, “nationalistic” rhetoric is condemned – and “nationalistic rhetoric” seems to include any overt expression of concern about the future of a particular nation qua nation. But Europe cannot exist as its own political entity commanding the loyalty of its population unless the people themselves place their primary political loyalty there and not in their own linguistic communities. This can only happen if political leaders within each nation make the case for that, something they have conspicuously chosen not to do.

Whither the Ins?

This report’s failure to even confront this issue means it fails to provide any serious guidance for establishment politicians – centre-left or centre-right – who want to adapt to the populist challenge. The Blair report is right to worry about challenges to democratic values, but it fails to see that treating one’s own citizens with contempt is perhaps the surest way to assault those values imaginable.

“Left” populists tend to focus on socially conscious, often young and educated, voters angry about economic decline as well as issues like climate change.

“Centre” populists, a category the ideologically blinkered report authors overlook, like M5S, ANO, the Pirates, or Iceland’s Centre Party, focus on government transparency and prioritise “getting things done” over any particular governing ideology.

Politicians and parties that do try to listen to the unheard find that they will be rewarded:

- This so far has been often seen on the centre-right, as leaders like the Netherlands’ Mark Rutte and Austria’s Sebastian Kurz shifted their parties’ tone on immigration and saw voters shift their allegiance from populist parties to theirs.

- This shift is also seen in Sweden, where the centre-right Moderates elected a new leader last fall, Ulf Kristersson, who has shifted the party’s stance on migration. The Moderates poll standing has risen significantly since then while that of the country’s blue-collar populist party, Sweden Democrats, has declined.

Savvy centre-left politicians have made similar shifts too:

- Norway’s Centre Party, traditionally a governing partner of the centre-left Labor Party, moved towards a more questioning tone towards the EU and foreign trade after it elected a new leader, Trygve Slagsvold Vedum, in 2014. It nearly doubled its share of the vote in last September’s election.

- New Zealand Labor Party leader Jacinda Ardern upset the long-ruling centre-right National Party in that country’s 2017 election in part because she called for significant cuts in international immigration, a stance in line with the Kiwis’ longtime right populist party, and Labor’s new coalition partner, New Zealand First.

Nostalgia for past success is an understandable emotion, but the Blair Institute misleads the ‘In’ crowd when it suggests nothing ought to change from the 2000 consensus. Circumstances have changed since then, and a rational citizenry wants new policies to reflect new challenges. The British Conservative Party has long been the world’s most successful mass party because it always knew how to change in response to a changed world. It would be more than ironic if the European centre-left, which came to power seeking dramatic, sometimes radical, change, would cease to be a serious political force because it emulated the inflexible conservatives whose rigidity it once mocked.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe