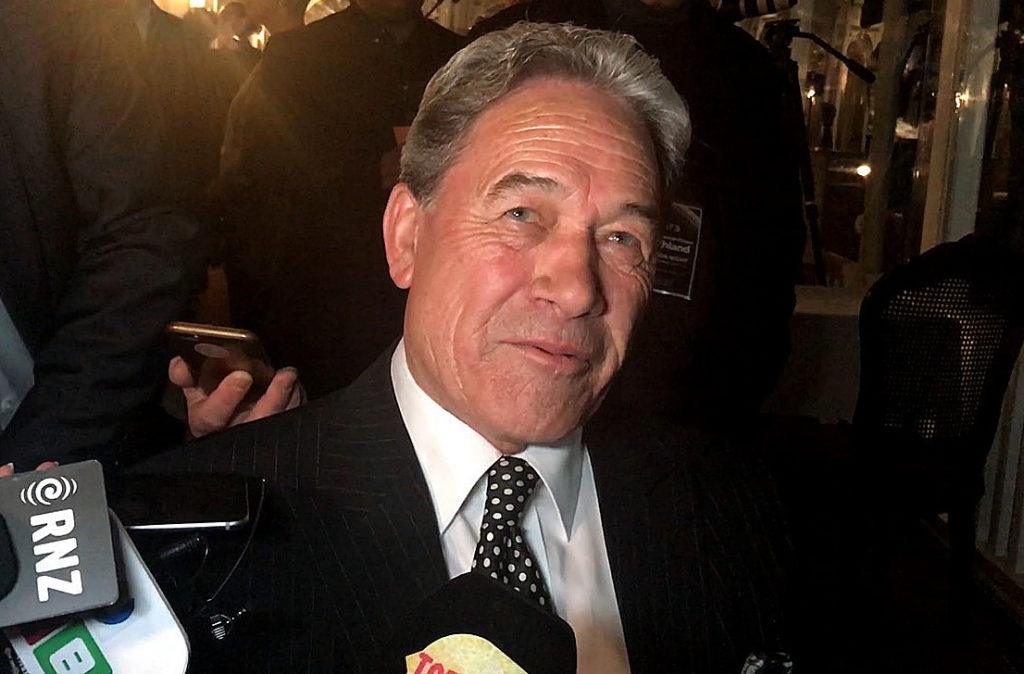

New Zealand’s new PM Jacinda Ardern has teamed up with the populist NZ First party Credit: Google Images

New Zealand is blessed compared with other nations. The economy has quickly recovered from the financial crisis and a massive 2011 earthquake to grow at over 3 per cent a year since 2012[1. https://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/economic-forecast-summary-new-zealand-oecd-economic-outlook-june-2017.pdf]. Unemployment is low and dropping, and international rankings of happiness or prosperity regularly show the little country at or near the top[2. https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/news/90654968/new-zealand-continues-to-top-polls-of-worlds-best-countries]. The country is so serene it was consumed with sorrow recently upon the death of the new Prime Minister’s cat, Paddles[3. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/98663593/paddles-jacinda-arderns-cat-has-been-killed-apparently-run-over].

This is not the sort of country one would think might be conducive to populism. Yet the new Prime Minister, Labour’s Jacinda Ardern, owes her position to a coalition with a long-time populist party, New Zealand First. NZ First, led by Sir Winston Peters, has been represented in Parliament for most of the past two decades, consistently calling for immigration restrictions and an economic policy that places national interest ahead of globalisation or economic efficiency. NZ First’s continued appeal is a reminder that prosperity alone will not quell populist instincts. Both Left and Right need to address these instincts if they want to establish a stable government.

New Zealand’s centre-right party, the National Party, is not in government despite being the country’s largest, precisely because it chose not to do so. Under its longtime leader, John Key, it won three consecutive elections by owning the political centre. Pledging, and then delivering, on pragmatic governing that placed ordinary citizens’ concerns first, National won between 45 and 48 per cent of the vote in each election, astonishingly high figures in an age of political fragmentation.

Despite this, National had to rule in coalition with smaller parties because of New Zealand’s Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system. Modelled on Germany’s model, Kiwis cast two votes on election day, one for an individual who is elected in a single-member district on a first-past-the-post basis and another for the party they want to see form government. 71 seats are awarded via single-member districts, while 50 are given via proportional representation. The total for any one party of district and PR seats added together must equal the share that would have been awarded had all seats been allocated via PR. Since a party must receive 5 per cent of the national vote to win any seats via PR, making some parties ineligible for seats unless they won a single-member district, in practice a party must win close to 50 per cent of the vote to be able to rule without a partner.

National had been able to avoid coalition with NZ First by carefully exploiting loopholes in the electoral system to effectively pre-select its partners. Two tiny parties, the centrist United Future and the libertarian ACT, were granted single-member seats that National would not seriously contest. National’s strong party vote would effectively make up the loss of those seats via PR while their allies would get into parliament when their party vote totals would otherwise have kept them out.

National was able to choose a third partner, the Maori Party, because of the country’s unique way of ensuring representation for its indigenous population. Maori voters can choose to enroll on a separate electoral register consisting solely of indigenous voters. They vote in one of seven separate electorates reserved solely for indigenous voters and who can only elect Maori representatives. Furthermore, any party that wins a district seat is entitled to the number of seats it wins by PR (even if its party vote falls below the 5 per cent threshold). The Maori Party thus had greater political power than its small potential voting base would suggest, because it could gain seats running solely on issues important to indigenous voters. That way, it gained seats nationally that more broadly based parties could not hope for.

This strategy worked brilliantly for National under Key. In its first victory, in 2008, National won 58 seats on its own while its partners won another 11, giving the government 69 of the nation’s 121 seats. Despite the twin economic shocks that quickly ensued, National won re-election in 2011 with 59 seats of its own, adding 5 from its partners. Key’s final win, in 2014, saw National garner 60 seats while its partners added another 4. Its main rival, Labour, meanwhile had dropped vote share in each of these elections, obtaining only 25 percent in the 2014 election. It looked like National had found the magic formula for winning elections and governing the small country.

A closer look, however, shows that its victories owed as much to the division or ineptness of its rivals as to its own brilliance. Labour chose to run to the left in each of the last two elections, campaigning to institute a tax on capital gains (New Zealand currently has no such tax if the gains are derived from investments within New Zealand). Voters who were doing well themselves, however, were uninterested in waging class warfare for the sake of it, rejecting Labour’s ideological appeal. Socially conservative voters, meanwhile, supported a new party, the Conservatives, giving it nearly 4 per cent of the vote in 2014. It was unable either to win a single-member seat or cross the 5 per cent threshold, effectively depriving its voters of any parliamentary representation.

NZ First, meanwhile, kept creeping up in support. It failed to enter parliament in the 2008 election, but regained representation in 2011 by winning 6.5 per cent and gaining eight seats. It increased its totals to 8.7 per cent and 11 seats in 2014. Thus, despite increasing prosperity under National’s rule, populist sentiment increased substantially during its time at the top.

Increasing immigration was certainly one of the main reasons for NZ First’s rise. The booming economy started to suck potential workers into the country. Many were New Zealanders who had left mainly to Australia, in search of work, but many were foreigners, especially Chinese citizens. New migration had soared from 2012, reaching record highs of 72,000 a year in 2015 and 2016[4. https://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/Migration/IntTravelAndMigration_HOTPApr17.aspx. See also https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/22/new-zealand-immigration-hits-record-high]. This seems to be a small number, but New Zealand has only 4.7 million residents. Projecting New Zealand’s immigration rate onto the UK population of 66.5 million would mean the UK would have over 1 million immigrants annually; doing the same to the USA’s population would mean the US would have nearly 5 million immigrants a year.

Despite these data and polls showing NZ First rising in strength, National chose to do little to address migration concerns. While Peters campaigned to cut net migration to 10,000 per year, National’s new leader, Bill English, refused to call for any numeric limit on immigration. He merely said that National would classify immigrants earning less than NS$42,000 per year as “low-skilled” and allow them to stay for three years.

Before last month’s general election National was clearly intending to reform the exiting coalition, despite the long-term fall in its partners’ strength. Labour, though, was desperate to get back into power and did something almost never seen, dumping its leader, Andrew Little, less than two months before the vote and installing 37-year-old Jacinda Ardern in his place. Ardern wasted no time in revamping Labour’s policies, jettisoning the call for increased capital gains tax and committing to reducing net migration to 20-30,000 per year. The latter move was clearly designed to position Labour for a potential coalition with NZ First.

Ardern’s Labour also opposed the TransPacificPartnership trade deal, another key sweetener for the populist party whose economics were often more like the centre-left’s than the centre-right’s[5. Like many populist parties, New Zealand First favours a stronger role for government to lift the fortunes of the average citizen. For a fascinating take on its members and their priorities, see https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/18-07-2017/what-really-makes-nz-first-tick-i-joined-the-party-and-headed-to-their-jamboree-to-find-out/].

The result was astounding. Labour rocketed up from 24 per cent before Ardern’s appointment to over 40 per cent just five weeks later. Moreover, she had done this by taking votes from all the main parties, including NZ First whose poll averages dropped from 12 per cent to 9 per cent[6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Opinion_polling_for_the_New_Zealand_general_election,_2017#Graphical_summary]. While National recovered at the end and took first place again with 44.5 per cent, its traditional partners utterly collapsed, receiving only one seat between them. Thus, National’s failure to adapt to the national mood meant it was in a weakened position as it prepared to negotiate a coalition with its only available partner, NZ First.

Ardern’s new government rests squarely on her partnership with NZ First. The coalition agreement is vague in some parts, but reducing new migration is clearly one of her primary goals[7. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-21/ardern-rejects-scope-of-new-zealand-kingmaker-s-immigration-cuts]. The agreement also includes other long-time goals of Peters regarding retirement policy and increased investment in New Zealand[8. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-21/ardern-rejects-scope-of-new-zealand-kingmaker-s-immigration-cuts]. The groundwork is thus laid for a long-term alliance between the left and the populist centre.

New Zealand First’s appeal and success should be a stark warning for mainstream parties across the globe. For those on the left who recoil from addressing concerns about migration, it shows how difficult it is for even a centre-left party with a charismatic leader to gain government without some ability to engage working-class populist concerns. For those on the right, it shows that even honest, prudent government that achieves its growth goals cannot maintain its leadership without addressing the cultural concerns that mass migration and a global economic focus create.

New Zealand First’s success shows that supporters of moderate populism may just be like the hobbits from the Lord of the Rings film series that brought international tourist attention to the little nation: the provincial people whose beliefs and character can save the world.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe