Credit: Dennis Van Tine/Geisler-Fotopres/DPA/PA Images

The left was founded by and for working class people. Now, it’s in crisis: Working class voters are abandoning the left just as the left is abandoning them. Twenty years of experience on election campaigns across Europe and America, as well as two years grappling with YouGov data, have frightened me about the future of the left. But understanding how it’s future might be secured depends first on understanding how the left not simply missed the current anti-establishment surge, but helped to create it.

The seeds of today’s discontent were sown in the left’s response to the political victory of free market economics in the 1980s and the rise of globalisation. This right-wing economics inherently decreases the power, incomes, and dignity of working class voters, but rather than champion their cause in the face of this (as traditionally the left has done) it instead moved to compete with the right for the affections of middle and educated upper-middle income voters. Working class voters, in turn, abandoned the traditional social democratic left as their own situations worsened. Furthermore, attracting the educated middle and upper middle classes meant adopting their views on internationalism, migration, and other cultural issues that further widened the gap between the left and its traditional voter base. This cleavage between high- and low-income voters has created an existential crisis for the left at the same time as it’s given political space for working-class, anti-establishment politics to emerge.

The modern left came to being after the 1848 revolutions in Europe, with the express purpose of redistributing wealth and power from the capital-owning few to the labouring many. Industrialization’s rise created increasing numbers who demanded greater political and economic power. The major party on the left in virtually every major OECD country was founded in this period by people experienced in organizing or championing the cause of industrial labourers. The political victories these parties started to achieve in the 20th century were always upon votes from this class of people.

Later in the 20th century, the left folded into its coalition groups that the right had shut out, such as women, ethnic minorities, disabled people and the LGBT community. Alongside this expansion of the left’s tent, its moral purpose remained unchanged. But in the post-Thatcher/Reagan/Kohl era, the left significantly shifted its focus from redistributing economic power to merely redistributing the proceeds of capitalism through taxation and public spending. As globalisation took hold of power and wealth across the world, the “Third Way” left of Clinton, Blair and Schroder sought to mitigate the worst excesses of the market rather than reshape or challenge it directly.1 In fact, these politicians went further by embracing flexible labour markets, free trade deals and free movement of peoples. Their adaptation of Crosslandite2 politics, whereby the market creates money that is taxed by the state to ameliorate its worst excesses, was magnified to an extraordinary degree.

The consequence of third way politics, globalisation and deindustrialisation was to detach working class voters from the left. As former Labour leader’s Ed Miliband pollster James Morris has noted, “Between 1997 and 2010 New Labour lost three working class voters for every one middle class voter that it lost.”3

In the 2016 US Presidential election, Hillary Clinton grew her vote from Barack Obama’s 2012 level of support amongst high income voters, but lost support from Barak Obama’s standing amongst low income voters4: and with that, the White House was Trump’s.

In Germany, the embrace of Schroder’s labour market flexibility with his long-term vision in the Agenda 2010 Reforms5 was so catastrophic that it led to the creation of a split within the SPD6 and the consequent loss of every Bundestag election after 2002. For different reasons and in different ways, this experience has been mirrored across the European left. As of today, in 30 European countries, the left only holds majority or senior coalition partner power in eight capitals.

What’s more, this experience is by no means limited to just the European left. The Democrats have only held the House of Representatives for six years since Third Way co-founder Bill Clinton won in 1992 whilst the Australian Labour party has only formed government for six of the last 21 years, and the New Zealand Labour party has only formed government for 9 years in the last three decades.

How high income voters split from low income voters

This decline can be explained in large part by the divergence in views between high income and low income voters in the left’s potential coalition. These cleavages are easily seen on hot button issues like national identity, family level economic confidence and immigration.

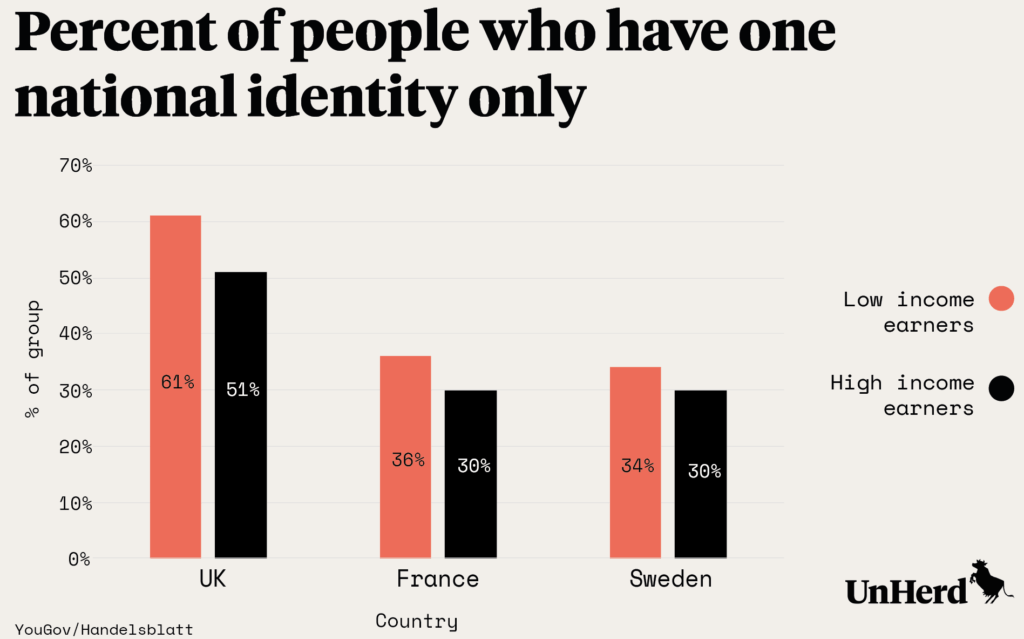

Low income voters are more likely to have a national-only identity as opposed to a mixed national and European identity.

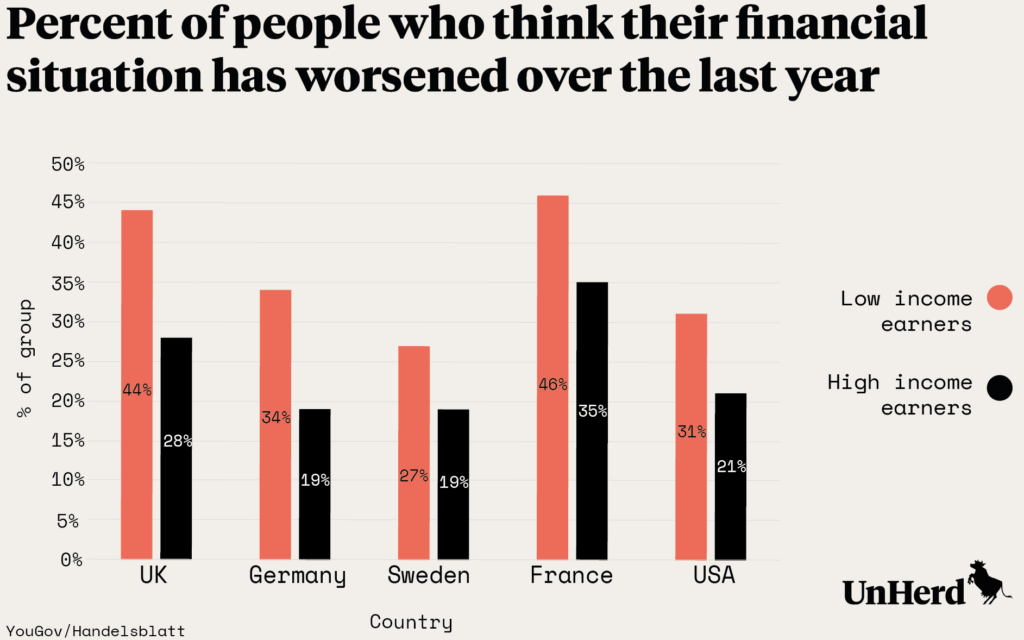

Low income voters are also more pessimistic about their economic situation and to think it is getting worse. Here the numbers tell broadly the same story across a range of countries.

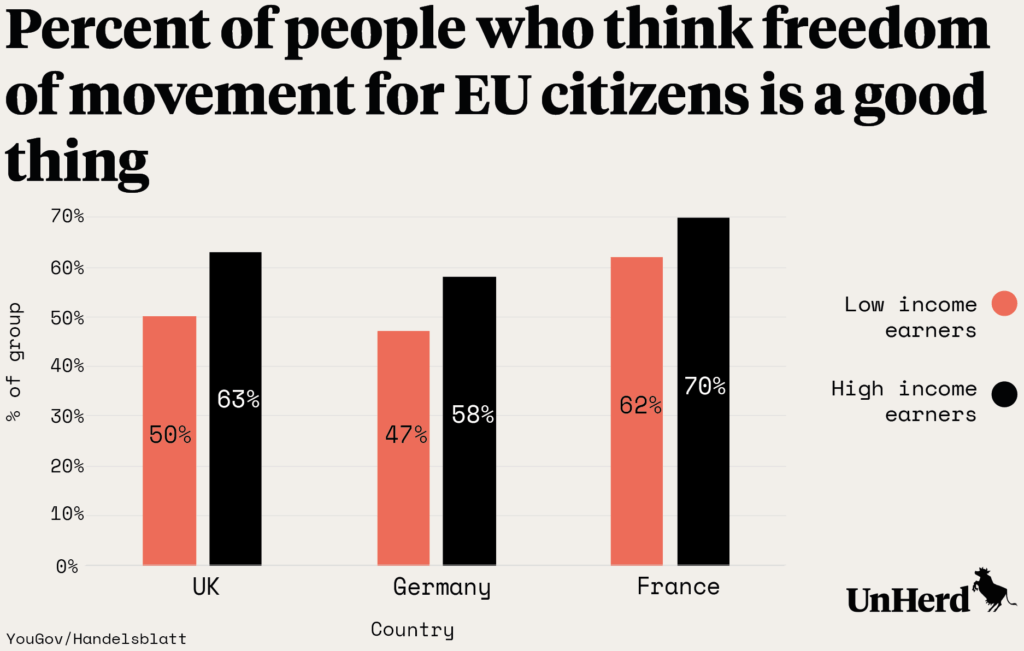

Low income voters are also less likely to think that freedom of movement for EU citizens is a good thing.

Taken together, these class divides illustrate the growing feeling of detachment and disassociation working class voters feel towards the left. From identity to immigration, the left has come to seemingly prioritise its internationalism over its economics.

In the case of the UK this manifested less in the left’s opposition to Brexit and more in its complete bewilderment at the pro-sovereignty, anti-status quo feelings of many low income voters.

In Germany, its taken the form of a fragmentation of the SPD vote. Die Linke, the Greens and the AFD are each able to either outflank the SPD (on the environment and spending, for example) or occupy political space the SPD cannot enter (anger at Chancellor Merkel’s million plus refugee policy as exploited by the AFD).

In France, the middle class/working class schism is so profound as to lead the Left’s votes to split along middle class defection to Macron’s En Marche, along with a smaller but worrying switching by low income voters to Le Pen’s Front National.

The disruption politics expressed by low income voters from Brexit to Trump to Le Pen and AFD is proof the left breaking its connection with working class voters. Instead of organising side-by-side as equals, the left too often adopts a position of patronizing dismissal – like the ever-present suspicion that concerns about immigration are simply code for racism. This creates a clear and present danger not just for the left but for the Western liberal democratic order: Low income voters, believing they have been dismissed as “deplorables” by leaders like Hillary Clinton, are moving to embrace radical, dangerous alternatives be it Trump or the AFD.

The politics of the contemporary left

The post-Third Way Left is now seeing the rise of Back to The Future leaders like Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders who embrace of 1970’s-style statist socialism with fresh billions.

Despite this, they continue to struggle to attract working class voters. Their embrace of a borderless world over all other politics heralds little care for the concerns of working class voters about place and identity. As for economic policy, the idea of Universal Basic Income neatly epitomizes their disconnect from working class values. Simply put, this is a concept antithetical to the left’s original principles of contribution, value and dignity in the workplace. In many ways, it represents the ultimate surrender to the market as it abandons any attempt to respect and empower low income or low skill workers in the economy and instead embraces welfarism in its most terrifyingly pure form. Not surprisingly, adoption of the UBI or similar variants has failed to dilute the appeal of populist parties or figures for working-class voters who want dignity as much or more than a check.

Where the left should go next

It would be a mistake, however, to think that the left’s future is without hope. For as Corbyn’s rapid and dramatic transformation of a twenty point poll deficit into a narrow defeat demonstrated, the left still has the capacity to surprise and change.

Corbyn and Sanders are in some ways throwbacks to the classic left. Their successful embrace of movement politics to activate huge numbers of activists, particularly within the Left’s youth, green and trade union wings, is a modern version of what social democratic and labour parties did a century ago. Furthermore, while flirtations with ideas like Universal Basic Income may belie their welfarism, they have been far more willing to challenge the market than their Third Way predecessors. They have demonstrated a certain blue collar appeal to voters left behind by Globalisation whom the regimes of Clinton, Blair and Schroeder alienated with their embrace of free trade deals, deregulation and labour market flexibility.

But just as the Corbyn/Sanders Left fails to understand the importance of the dignity of work with its welfarism, so to it fails to connect with the working class on issues of identity and place, instead prioritising, as the writer David Goodhart has said, the citizens of Everywhere over the citizens of Somewhere.[10. David Goodhart: The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics]

To address this disconnect, the left should look to ideas like Britain’s Blue Labour thinking, with its emphasis on faith, family and flag as hallmarks of a left that could both understand and participate in the politics of place and identity. The left should seek to grow the political space it occupies, moving out of its comfort zone in areas like equality, fairness and the state into areas that in recent years it has ceded too easily to the right: contribution, responsibility and community.7

A good example of this politics is the Dutch PvdA leader, Lodewijk Asscher, who experimented with a politics that sought to reassemble the left’s middle and working class coalition. Whilst Asscher’s rise to party leader mere months before the March general election meant that there was little time for his pro-work, pro-contribution politics to take firm root, the messaging and policy examples of his campaign are worth studying to understand how the left might put Blue Labour ideas into practice. For example, when it came to refugees, Asscher both embraced the in-country refugee community while demanding future refugee flows be shared equitably across the EU. Asscher also applied his pro-contribution politics to demands for ‘paying in before you take out’ on welfare alongside a hardline on multinationals that fail to pay their fair share of taxes and exploit workers.8 In each instance, Asscher sought not to pit low and high-income voters against each other but rather to create a politics acceptable to both.

The left would do well also to heed the words of former US Vice President Joe Biden. Long a champion of blue collar voters in the Democratic Party, since leaving office Biden has been exploring a politics that emphasizes the centrality of work.9 As Biden writes: “My father used to have an expression. He’d say, ‘Joey, a job is about a lot more than a paycheck. It’s about your dignity. It’s about your self-respect. It’s about your place in your community.’ And every coal worker in West Virginia or steelworker in Scranton who lost their job will tell you they didn’t just lose a paycheck but much more.”

In putting work at the heart of the left’s renewal, it could embrace the responsibility of actors beyond the state to help bring about change – be it community, charity, churches or trade unions. The left has a rich tradition of organising for change without relying on the magic money tree of state public spending to solve every problem. This matches the instincts of many working class voters who do not look to the state for a hand out but might welcome allies on the ground in a fight with bosses for better pay and working conditions. Here, the work of the US’s Industrial Areas Foundation10, and particularly the community organising traditions of the left as exemplified by leaders like Arnie Graf11 are sources of hope for reconnecting with working class voters in terms of organisational tactics.

In creating a new politics for the left, ideas like that of the left thinker Jon Cruddas12 about how “power is the new money” should be embraced. In an era in which “Take Back Control” is a startlingly effective political message, the left should embrace a dramatic devolution of power and money not just from central to local government but from the state to the community with ideas like participatory budgeting13 or Total Place experiments14 representing just a fraction of the potential of a politics of redistribution of power. The common thread in all of these ideas is the promotion of agency at the individual and community level.

These ideas are necessary, but not sufficient, to return the left to its founding partnership with the working class. For the breach to be fully mended and the relationship to be restored anew will take a new political economy by the left, one that does not kowtow to the market as the Third Way did or seek merely to replace the market as a bullying force for individuals and communities with the state as a new bully.

Rather, what is needed is a political economy that redistributes power, not just wealth, within the economy itself, granting workers agency over their work lives, their pay and their organisation’s future. If the virulent strain of globalisation, automation and mass movement of workers is the loss of agency by workers than the left’s new political economy must make the expansion of worker agency the litmus test of all its politics.

Here state action is to be welcomed with vocational education raised to the same level of respect and funding as academia, worker representation on company boards as in Germany, regional banks to ensure thriving economies beyond capitals and financial services, a highly interventionist industrial policy and greater regulation of markets (including and especially the labour market) as well as a more pro-worker position on trade deals. By so doing, the left can use the strengths of both state and of organising to fundamentally rebalance power between the forces of globalisation and workers themselves.

The left at its best is about ensuring that human dignity receives equal hearing in the public square with utility and excellence. The left’s political economy should promote the agency of workers, the creation of value and contribution and must resist the despair of welfarism even in the face of globalisation, deindustrialisation and automation. A left that returns to its roots will see the grandchildren of our founders work once again in partnership between middle and working classes alike. Failure to do this, coupled with the inherent inability of free marker economics and globalisation to confer that dignity and respect on all workers, will not only mean the continued failure of the left but will lead to yet more anti-establishment politics of the Brexit, Trump and even AfD variety. That fear alone should motivate a more creative and conciliatory new marriage between the middle and working classes.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe