President Donald Trump divided the country when he spoke over Billy Graham’s casket. (Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

Earlier this week, a portion of Washington DC slowed to a quiet hum, if not a full stop, as the body of the evangelical pastor Billy Graham was brought to lie in the rotunda of the Capitol building. During the ceremony that followed, President Trump spoke on behalf of the nation to honour the man he called “America’s pastor”.

His tribute immediately fell into the now familiar grooves of American public discourse. Those who admire Trump admired the speech; while those who dislike him, railed at the President’s alleged hypocrisy. Even members of the Graham family were catapulted into, or catapulted themselves into, the melee. The admiration of Franklin Graham, one of the pastor’s sons for Trump is well known: he’s said that God put Donald in the Oval office. But one of Graham’s granddaughters, Jerushah Armfield, proceeded to attack the evangelicals who support Trump, calling them hypocrites:

“…the term ‘evangelical’ was coined primarily to depict a branch of Christianity that was breaking itself away from fundamentalism. Now fast forward, you know, 20 years, it really kind of has started to represent — especially in the 2016 election — a branch of Christians that seemed to be a little more conservative and a little bit more hypocritical.”

It all served as a reminder – if reminder were needed – that in the age of social media and megaphone opinions, there is almost nothing that can bring a nation like America together. Even figures who might be expected to be unifying, can cause dissension simply by living – or dying – amid the mass-broadcast political and culture wars which are now raging across everything.

It should also be said that many of those voicing their opinions did have a point. Donald Trump may be an unlikely figurehead to lead the mourning of a man who even his fiercest critics would concede to have been a devout man of God. But he is the American President, and rose to the occasion as much as anybody could.

And to a great extent, America’s political and culture wars are still echoing with the repercussions of that extraordinary period in the 1990s. For can anybody truthfully claim that Bill Clinton is any more a man of God than Donald Trump? Can anyone seeking to claim that Donald Trump is hypocritical or opportunistic in his attitude towards religion as a whole, and his evangelical voters in particular, credibly take a different attitude towards Bill Clinton?

During his time in office – lest anyone forget – President Clinton was never above being photographed humbly slipping into the Oval office as though he did not expect to be observed, with a copy of the Bible placed coyly yet clearly under his arm. Were President Clinton’s well-timed and well-placed displays of religiosity one thing and President Trump’s another?

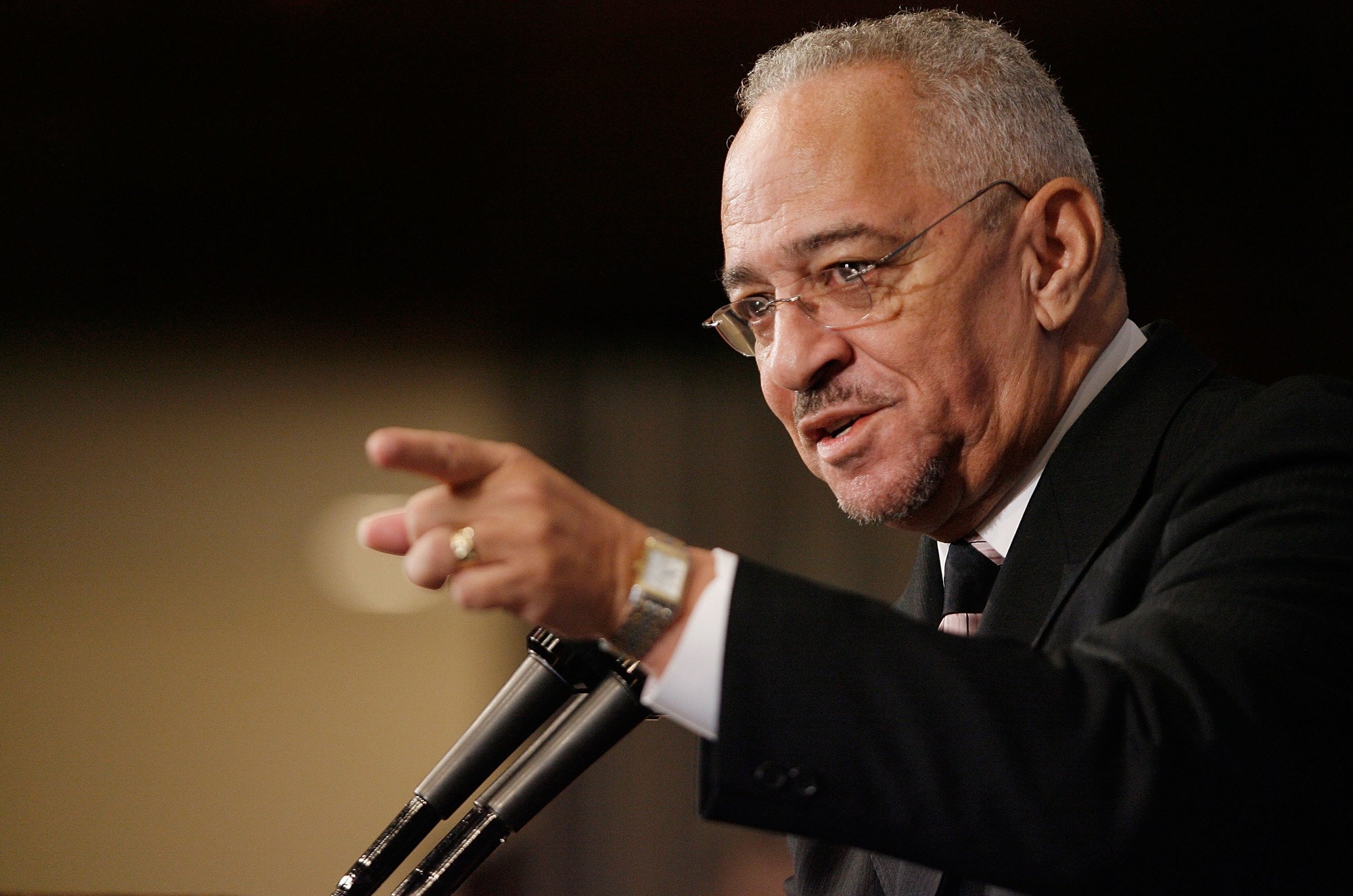

If so, then what is one to make of President Trump’s immediate predecessor, Barack Obama? A man who was happy for years to attend the church of Jeremiah Wright. When that pastor’s bigoted views became known to a wider public, he was dropped by the then candidate at lightning speed, with a profession of unawareness thrown in. Was that an expression of devoutness or consistency? Or was it the expression of a cynicism and opportunism equal to any President before or since?

The truth is, voters are capable of two things with which they are rarely credited. The first is a degree of nuance. People need not believe that a particular leader is a member of the Sisters of Mercy in order to make a value judgement over which candidate will better advance their views on social and fiscal matters. Indeed, it is even possible, on occasion, to encounter voters supporting someone precisely in order that they further an agenda they known to have been adopted cynically.

The second thing that voters are too rarely credited with is a degree of memory. Henry Olsen recently wrote about the inability of Tony Blair and other European political figures to understand the true currents of ‘populism’. If there is one reason for that, it is that they seem unwilling to even keep in mind what the public remember all too well. The UK electorate was this week treated to a former prime minister, John Major, berating them for not sharing his own views about the EU.

In Britain, as in America, the public continues to be not only misrepresented and misunderstood, but herded, hectored and actively berated for their choices. This can only ever exacerbate the deep divides which now turn even a moment of mourning into a furious political game.

Those who would like to aspire to a healthier form of politics must work to find ways through this morass. One place to start might be to recognise that short-term memory loss is more prevalent among the political class than among those to whom they should be trying to appeal.

Catch up with our series Believers in Trump which closely examines the relationship between the religious right and current politics

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe