Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

This addition to our series examining different cultural representations of flyover country takes a look at the inspiration behind the series

As Donald Trump rose to political prominence in 2016, Americans searched for someone who could explain his success.

They found that person in JD Vance, a 30-something, softly-spoken graduate of America’s top law school, Yale – exactly the sort of elite insider the populists were rebelling against.

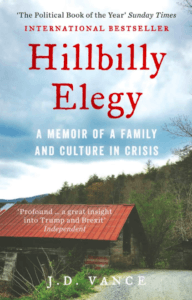

But his breathtaking and eloquent first book, Hillbilly Elegy: a memoir of a life and culture in crisis, just goes to show you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. It remains the single best introduction to the poor, white, working-class lives and world views of the people who put Trump in the White House. And it’s told through Vance’s own life story.

Vance was raised in a broken, single-parent household in a declining industrial town in southwestern Ohio. Neither his parents nor his grandparents attended college. Crucially, this family had emigrated from, but remained deeply tied to, rural Appalachia. This, where the hillbillies hail from, is ground zero for fervent Trumpism. It’s what Stoke or Sunderland were for Brexit; Henin-Beaumont for Marine Le Pen. Understand the people who live here, and you understand their political movements.

Appalachians, seen through Vance’s eyes, are a study in contrast. At times militantly self-reliant, at times abjectly fatalistic; they are capable of deep, tribal violence and acts of supreme self-sacrifice and compassion. Above all, Appalacians are proud. They desperately seek to control their own fates even if time and again their poor choices or shortcomings cause them to fail.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe