Tom Merton, Getty

Capitalism needs rebooting. The British economy no longer works for millions; too few people under thirty can afford a home[1. .UK Perspectives 2016: Housing and home ownership in the UK, Office for National Statistics, 25 May 2016]; and there’s a shortage of long-term investment, especially in certain innovative industries.[2. John Kay, The Kay review of UK equity markets and long-term decision making, July 2012] Meanwhile, the CEOs of our largest businesses enjoy runaway rates of executive pay.

Since the 2007 financial crisis, there’s been a growing sense among Western states that something’s wrong with free market capitalism. But it’s easier to identify what we don’t like about our economy than it is to offer real remedies. Those that talk about the need to reform capitalism are often a little hazy when it comes to the detail. Or else, if they do sound specific, it’s because they become highly prescriptive. So much so that their idea of a reboot can be boiled down to a free market that is less free.

So here’s what has and hasn’t happened. The increasingly “crony” nature of capitalism is not understood by many pundits, so debates about corporate reform have deteriorated into facile discussions of whether one is pro- or anti- business. Faced with public disquiet about executive pay, politicians have handed down elaborate compliance rules while doing nothing to enable those that own the firms to exercise control over those that run them. In response to a shortage of long term capital, the government has created a British Business Bank to dish out state-backed loans, preferring to allocate resources by top down dictat.

Increasingly aware of the serious housing shortage in the UK, the government has also created a system of state-subsidised mortgages, George Osborne’s Help-to-Buy scheme (to be expanded under Theresa May – to Liam Halligan’s dismay). This has been great news for those allocated subsidised mortgages, but it has not of itself built a single additional house. Instead it has pushed up the price of houses yet further, while establishing a system of mortgage-rationing.

One layer of corporatist interference has been laid upon another. And, eventually, the weight of it all will fossilise rather than free the market system. What we need, instead, is to liberate capitalism. But before outlining how we do that, it’s worth revisiting the history of how free market capitalism came to be.

Historic perspective

For most of recorded human history, economic resources have been allocated by force – or at least some sort of top down direction – and people remained poor. In various river valleys around the world – the Nile, Euphrates, Ganges or the Yangtze – there existed hierarchical societies in which a tiny elite presided over a mass of toiling peasants.

Until remarkably recently, self-organising economic systems – and the intensive economic growth they bring – were rare. Where they did exist, they tended to emerge on the margins, beyond the reach of emperors and warlords. In the Middle Ages, Venice flourished on an inaccessible mud bank off the north-east coast of Italy. In the sixteenth century, the Dutch began to prosper in another backwater on the other side of Europe.

Which is not to say that self-organising economic systems emerged from a state of anarchy. In a capitalist system, capital by definition resides in private hands. And in private hands, capital needs to be able to mobilise labour and other resources to produce wealth that generates a return. Yet in order to do that, there needs to exist an underlying legal order that enables the capital, labour and risk to come together – and to be effectively managed.

The Venetians didn’t become “frankly and efficiently capitalistic”[3. Frederic Lane, Venice, A Maritime Republic, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973] simply because they were beyond the reach of the Holy Roman Emperor. They had also developed the commenda contract system (the idea having been borrowed, some say, from the Islamic world on the other side of the Mediterranean[4. For more on how the Venetians borrowed ideas from the Islamic world see: Benedikt Koehler, Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism, 2014]). The Dutch prospered not just because they had kicked out the Habsburgs, but because they devised an early version of the Joint Stock Company, enabling them to emerge as traders, processors and middle men.

Something similar emerged in England, initially with charter companies and then Joint Stock Companies after the 1844 Act made incorporation easier. Limited liability, a privilege, was extended to investors, encouraging investment, defining risks – and placing obligations on those granted such privileges.

Commenda contracts. Charter companies. Joint stock companies. Each was, in its own way, an attempt to address the same question: How do you ensure that those who own an enterprise or business by investing in it, control those that run it day-to-day?

Venetian investors who put up the capital for a voyage wanted assurances that the person captaining the expedition would not diddle them. So, the commenda system set out how profits would be shared, and what cargo the captain might carry on his own account. It even created a form of limited liabilities for ship losses, too.

The charter that established the Dutch Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie did something similar.[5. In the early seventeenth century, shareholders in the VOC constantly complained that they were not getting the full proceeds of profit from trade with the East Indies. One notable shareholder revolt in 1622 was rather reminiscent of some of the shareholder revolts we have seen in the City more recently.] When the English followed suit, creating their own East India Company, there was a similar balance between the interests of those that operated on behalf of the company, and those who had invested in it.

The question of how investors can control those that run their businesses is is as old as capitalism itself. It is not, therefore, anti-capitalist for us to ask the question anew today and explore the possibility of a better answer. It is, in fact, essential if our self-organising economic system is to survive.

Crony capitalism today

Capitalism today is in a mess because capitalists are no longer properly in control of their capital.

Many City boardrooms have become self-serving cliques, the directors no longer acting in shareholder interest. They are stuffed full of group-thinkers and able to select their own membership, ensure a herd-like mentality.

The corporate bureaucrats that the directors are supposed to oversee are often of mediocre ability[6. See for example: ‘How poor management is driving your staff away’, Chartered Management Institute, 1 February 2016] – yet are rewarded for taking risks with other people’s capital.

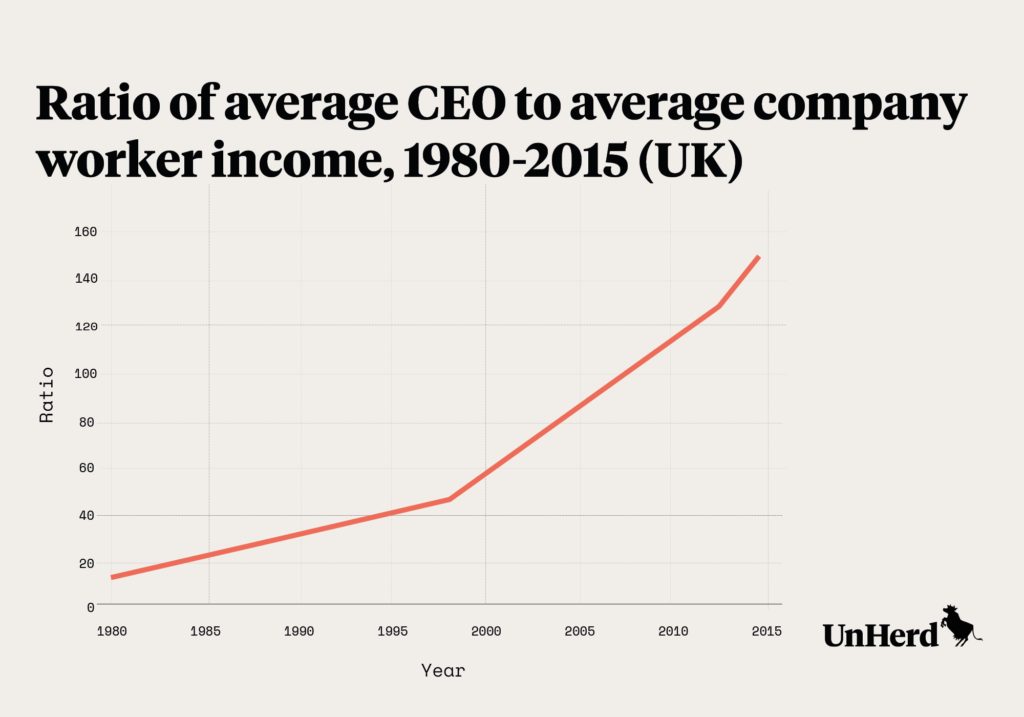

Soaring CEO pay is not a measure of the free market at work; it’s an indication that the system has been corrupted. Those that run firms are not properly overseen by those that own them.

FTSE 100 executive pay has increased far faster than the returns that investors in those businesses have made on their capital.[8. Weijia Li and Steven Young, An analysis of CEO pay arrangements and value creation for FTSE-350 companies, CFA Society United Kingdom, 2 December 2006] The system is hardly favourable to those that own capital – the capitalists. That’s because it’s not really a capitalist system at all, but a form of crony corporatism.

Investments in publicly listed firms are made through a convoluted chain of ownership that goes from investor, through pension pots, Individual Savings Accounts or mutual funds, via fund managers. Fund managers have little incentive to exercise real ownership responsibilities, acting instead as rentier investors. They claim a share of the dividends, yet assume too little oversight over the corporate bureaucrats in the boardroom, who are free to help themselves to an ever-larger share of the firms’ balance sheet.

It’s not only that capitalists don’t properly control their capital. The businesses in which they invest are often able to avoid free market competitive pressures.

Growth through graft, not competition

In a properly free market, business success should depend on providing happy customers with a product they want at a price they are willing to pay. Under our system of crony corporatism, business success often depends on graft: rigging regulations to oblige customers to take what they are offered at a price that suits the producer.

Across many sectors of the economy – from housing, energy and transport to the credit markets – regulatory compliance is almost more essential for a business’ bottom line than customer satisfaction. Wherever one looks, there are cases of producer regulatory capture and businesses lobbying to change the rules to give them an advantage over others. Here’s a standout example: In the early 1990s, the Germany car industry realised that it had an advantage over its US and Japanese rivals in terms of proprietary diesel engine technology. The only problem was that the market in automotive diesel engines was almost dead. They had an advantage in making something that few people wanted.

Their response?

They set about lobbying EU policy makers to make people buy diesel cars – and as UnHerd’s Harriet Maltby has set out, they had the power over German politicians to get what they wanted.

A whole host of pro-diesel policies were drawn up by the European Commission, often on the basis that diesel engines would help in the fight against climate change, since they emitted marginally less CO2 than ordinary petrol engines.

The system of subsidies and sweetheart deals put in place at the behest of the EC worked. EU consumers switched to diesel, buying more German cars in the process. In 1995, about one in ten cars sold in the UK was diesel. By 2012, over half were.[9. Daniel Hannan, Why Vote Leave, March 2016] But there was one slight problem: diesel is dirty fuel, emitting Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) and particulates – tiny, toxic molecules that penetrate our lungs, bodies and brains. The move to diesel might have meant some reduction in CO2 emissions but, overall, diesel was far worse for the environment. So how did the German car industry get around this inconvenient truth? Having rigged the rules to make people buy diesel, they also rigged the emissions tests.[10. For a more detailed description of the diesel scandal, see Daniel Hannan, Why Vote Leave.]

Crony corporatism didn’t only harm air quality in European cities and the health of millions of Europeans. It hurt European consumers, who paid for products when they would have been better off buying cleaner alternatives.

And, ultimately, it hurt the industry. While regulatory capture allowed European car manufacturers to take a wrong turn, car makers in Japan and the US have led the way with electric and hybrid innovation. Is it any surprise that the really exciting breakthroughs in automotive technology are taking place outside the EU?

Crony corporatism is bad economics. If regulatory capture by producer interests helps explain the relative decline of the European car industry, it also incidentally helps account for the relative economic decline of Venice and Holland in an earlier age.[11. Textile industries in Venice were heavily regulated, for example, which helps explain why Venice lost market share in the eastern Mediterranean. For more details on the way in which producer regulation led to the economic decline in Venice and the Dutch republic see Douglas Carswell, Rebel: how to overturn the emerging oligarchy, March 2017]

Europe’s recent diesel saga might have hurt the EU automotive industry, but producer capture is a problem in Japan, America and elsewhere. However much regulatory capture might harm prospects for overall economic performance, it happens because it suits the interests of individual businesses and industries – which is why they employ armies of lobbyists in the so-called ‘swamps’ of Brussels and Washington to help write the rules to their advantage.

To revive capitalism, we need reforms to give capitalists more control over their capital (their investments). And we need to re-think the way we regulate to ensure that businesses have to compete for customers to grow – rather than, as now, persuade politicians to adopt forms of regulation that advantage them over competitors. I’ll set out my solution to this challenge tomorrow.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe