Jack Ewing's book on VW's cheating of environmental regulations

There is something mendacious about the Volkswagen Beetle as a great symbol of 1960s counterculture. The bug-eyed vehicle of the Summer of Love, social liberation, and the anti-war movement was dreamed up as a Nazi prestige project, built by slaves with money stolen from labour unions, and driven by elites. Herbie was of Hitler’s creation.

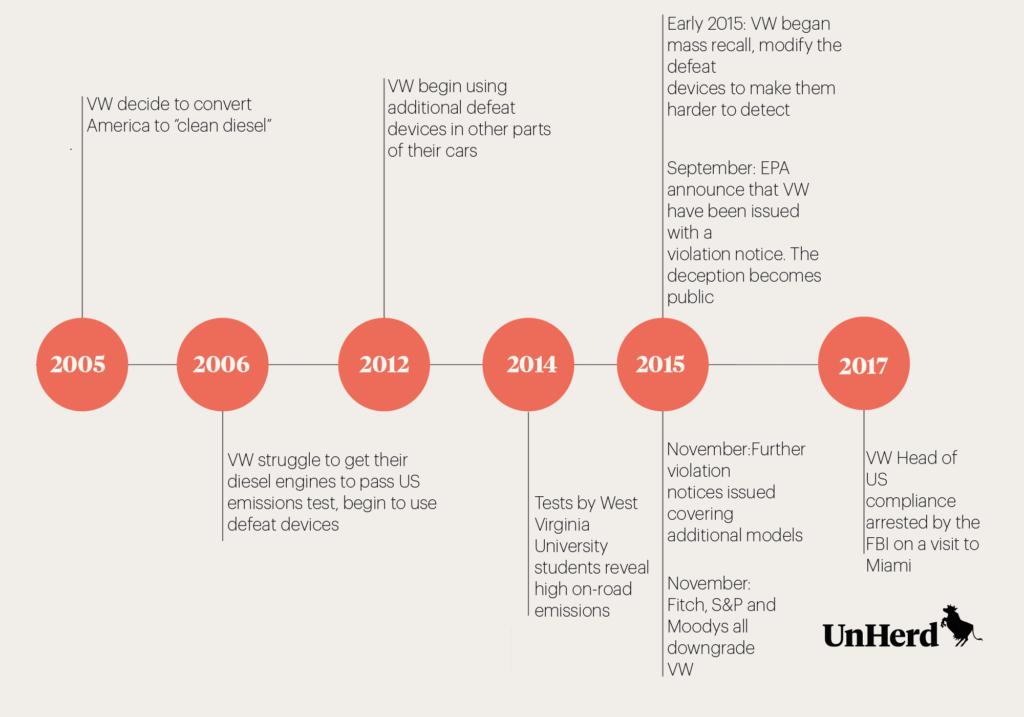

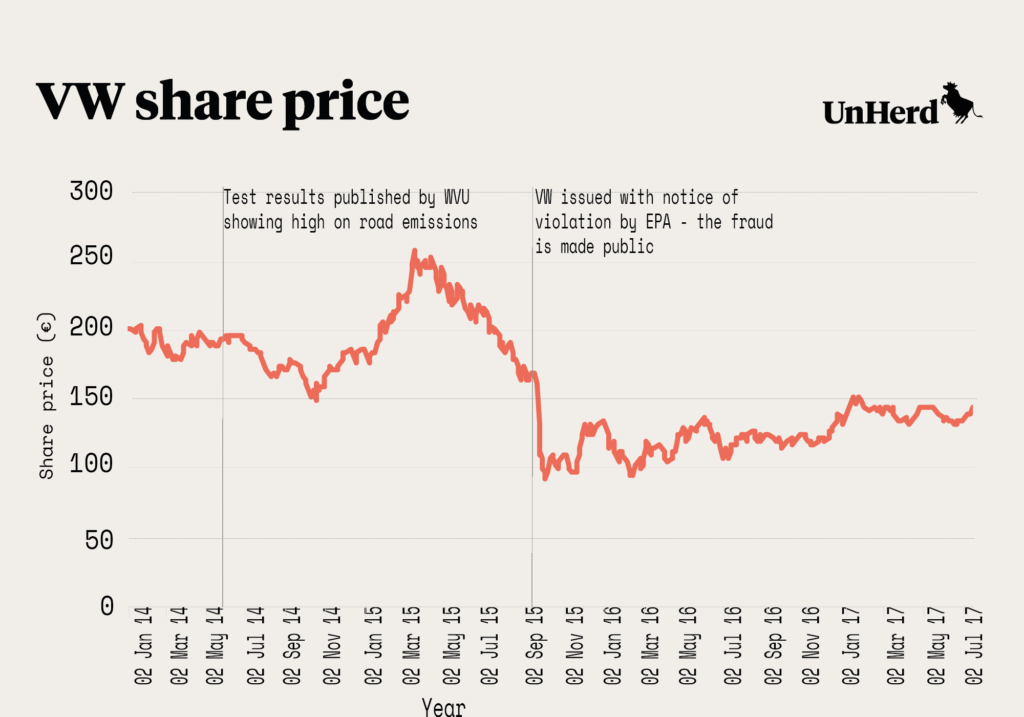

It would not be the last time that Volkswagen’s social credentials were based on soft ground. In 2015, the company’s missionary devotion to ‘clean diesel’ was exposed as a poisonous lie. Eleven million cars had been fitted with a ‘defeat device’, software that cheated emissions testing. “Volkswagen was involved in one of the greatest corporate scandals ever.”1

These are the words of Jack Ewing, European economics correspondent for the New York Times, who had been covering Volkswagen when the scandal made headlines.

This was to prove no normal tale of corporate fraud. No-one had lined their pockets with gold. There was none of the greed of Enron, only a hunger to go faster, higher, and further than anyone had before.

“This whole scandal was uncovered by a group of graduate students at West Virginia University with a $70,000 grant.”

Ewing is telling me what first drew him to look deeper at the downfall of a firm synonymous with German economic power.

“And that is all it took to really shake the foundations of this enormous carmaker.”

It was a modern day Aesop’s Fable, a corporate giant undone by its own arrogance, complacency, and the voices of the unheard. The makings of a book were there, and Ewing’s Faster, Higher, Farther: The Inside Story of the Volkswagen Scandal, is the result.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe