“Clinton is the one that approved NAFTA … NAFTA is the worst deal, one of the worst deals our country has ever made, from an economic standpoint … one of the worst deals, ever.”1

President Trump’s words are at odds with the collective wisdom that free trade is a powerful driver of progress. That by stimulating exports and investment, and enabling cheaper imports, free trade delivers a higher standard of living in nations that embrace it.

Yet, as his election victory showed, Trump had grasped a fundamental truth: that while free trade does indeed create winners, it also creates losers. Competition from lower-cost imported goods undercuts domestic production, and while new and usually higher skill, higher pay jobs are created,2 that is scant consolation for those whose livelihoods, even identities, are lost.

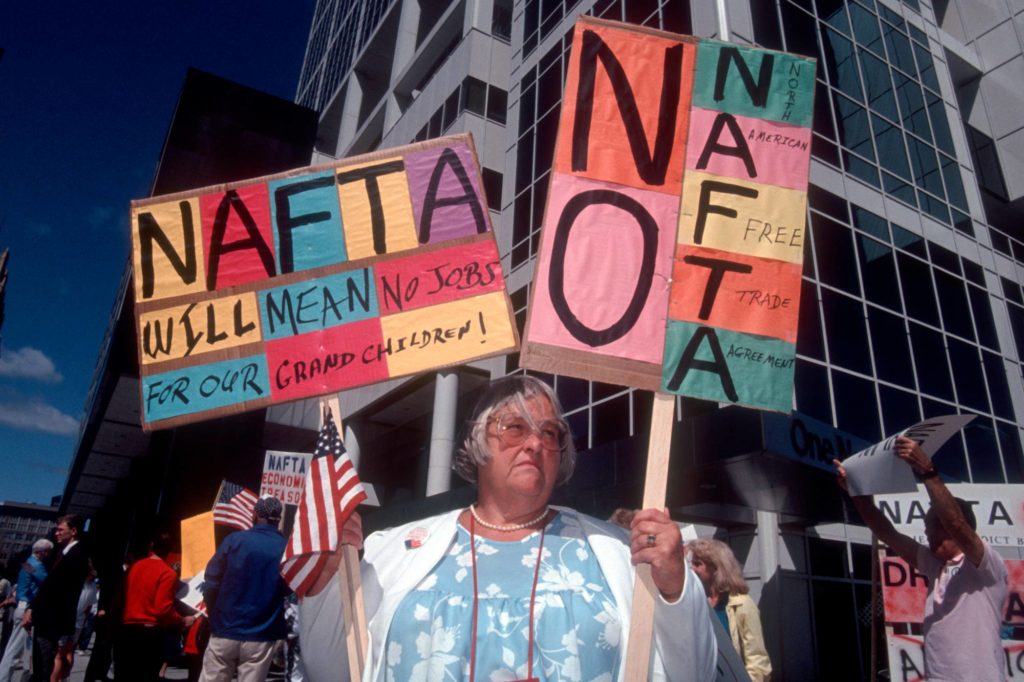

This is why the President has set his sights on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – reiterating at a rally for supporters in Arizona last week his belief that the pact can’t be saved. Nearly 25 years after it was signed into existence, NAFTA is a useful case study of both the benefits and the limits of free trade.

This free trade agreement between America, Canada and Mexico has always been controversial. Ever since 1992 presidential candidate Ross Perot talked of the “giant sucking sound” of jobs disappearing over the border, critics have lamented NAFTA’s impact on America’s manufacturing sector. And while NAFTA is by no means the only factor contributing to job losses – think China and advancing technology – the huge trade deficit between America and Mexico speaks for itself (the US goods trade deficit with Mexico was $63.2 billion in 2016, far exceeding the services surplus of $7.6 billion).

Twenty-five years ago, the the third party US presidential candidate Ross Perot argued (with rhetoric echoed by Donald Trump today) that NAFTA would see American manufacturing jobs ‘sucked’ to the south of the border by Mexico. The above debate took place with a much more youthful-looking Al Gore.

Which is not to say that the American economy hasn’t benefited – a review by the Council on Foreign Relations found a “modest but positive impact on US GDP of less than 0.5%”3 – but that the benefits were not being evenly spread. One study found a small net loss of around 15,000 jobs a year, but argued that for each lost job there was “several hundred thousand dollars of gains to the economy” – largely from increased productivity and lower prices.4 The problem – again – is that the workers displaced don’t necessarily move into the newly created jobs – and yes, lower priced consumer goods are helpful, but you still need a wage to buy them. And therein lies the point Candidate Trump grasped to such political effect (helping him win the swing states of the rust-belt): in celebrating the broader positives of creative disruption, we must not lose sight of the turmoil experienced by those being disrupted.

But while the NAFTA debate centres on America and its President’s hyperbole, the more interesting story is how the free trade pact has impacted Mexico.

Free trade is an engine of growth for developing countries… and so what happened to Mexico?

America (like Canada) is a highly developed economy, one that, whatever the rhetoric, was never going to compete with cheap Mexican labour. But for Mexico, NAFTA would surely act as a rocket-boost to their developing economy. Surely? Well, that depends on what you measure.

An International Monetary Fund paper assessing NAFTA’s impact after twenty years concluded that, while tricky to isolate the agreement’s specific affects, it “played an important role in boosting trade and financial flows in the region.”5

Additionally, we know that…

- In the two decades after NAFTA was implemented, Mexico’s exports to America and Canada more than doubled in dollar terms;6

- US foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico surged from $15 billion in 1993 to over $100 billion in 2016;7 and

- Studies suggest total factor productivity increased by between 5% and 10%.8

These findings are in line with the assessment of Jorge Castaneda, a former Mexican Foreign Minister, that: “Viewed exclusively as a trade deal NAFTA has been an undeniable success story for Mexico, ushering in a dramatic surge in exports.”9

As hoped, Mexico’s economy became increasingly integrated with their two free trade partners to the north – bringing new, higher skilled, jobs with better wages; faster technological adoption; and, according to the World Bank, reduced macroeconomic volatility.10

Mexico, it seems, was reaping the multifold benefits of the free trade dream.

And yet, as Castaneda actually goes on to say:

“But if the purpose of the agreement was to spur economic growth, create jobs, boost productivity, lift wages, and discourage emigration, then the results have been less clear-cut.”

Which essentially translates into: success depends on how you look at it. Wages did go up for those employed in the higher skilled manufacturing jobs – predominantly in the foreign-owned maquiladoras (factories) built along the Mexican-American border – and productivity did increase significantly within big businesses. But as McKinsey reported in 2014:11

“There is a modern Mexico, a high-speed, sophisticated economy with cutting-edge auto and aerospace factories, multinationals that compete in global markets, and universities that graduate more engineers than Germany. And there is traditional Mexico, a land of sub-scale, low-speed, technologically backward, unproductive enterprises, many of which operate outside the formal economy.”

Almost six in ten Mexicans work in the informal economy12 – which is partly cultural, but is also the result of tax incentives that encourage enterprises to stay small and social insurance costs for formally-constituted businesses. And according to McKinsey, traditional, small and unproductive firms account for a rising share of employment.13

At the same time, millions of Mexican farmers were displaced as a result of NAFTA, with the country experiencing a net loss of around two million agricultural jobs by 2007.14 Tariff-free trade is a good thing when there’s a level playing field, but US agricultural subsidies far exceeded those in Mexico (one 2003 article on NAFTA put American subsidies at between 7.5 and 12 times larger than in Mexico)15, making Mexican produce uncompetitive.

Which all helps explain why Mexico’s per capita GDP growth has been so dire at an average annual rate of 0.9% between 1994 and 2013. Mexico’s Latin American neighbours, including Brazil (1.8%), Chile (3.4%) and Argentina (2.5%)16 all performed better – and without NAFTA.

Perhaps most damning, however, is the lack of impact on poverty rates – something free trade is, rightly, heralded for helping alleviate (again, think China, where extreme poverty has plummeted and global trade soared). Using its own national measure, over 50% of Mexicans live in poverty – as was the case in 1994.17 Using the standardised method for tracking relative poverty, more than a quarter of Mexicans have been living below the poverty line between 1984 and 2010.18

Many commentators have questioned whether Mexico would have been any worse off had NAFTA not been enacted. And it is difficult to disagree with the Center for Economic and Policy Research’s conclusion that:19

“The end result has been decades of economic failure by almost any economic or social indicator. This is true whether we compare Mexico to its developmentalist past, or even if the comparison is to the rest of Latin America since NAFTA.”

The results of free trade are only as good as a country’s domestic policy

But perhaps we’re asking the wrong question. As the NAFTA negotiators head to Mexico for the next round of talks, rather than blaming free trade, perhaps America and Mexico should consider the domestic blockers to progress. Free trade is not, after all, a substitute for an effective state. As Victoria Bateman argued earlier in the week for UnHerd: a democratic, capable state – coupled with markets – is fundamental for prosperity.

Much more important in spreading prosperity and fighting poverty are a nation’s domestic policies. To take just a couple of examples.

- Both countries have an education and skills problem: just 21% of 25-34 year olds in Mexico have tertiary education, compared to the OECD average of 42%;20 and America is falling further behind advanced nations in science and maths attainment.21.

- And likewise, in both nations, access to credit is an issue. Low levels of domestic credit to the private sector in Mexico – unsurprising given the woeful protections afforded to creditors – is, according to economics professor Gordon Hanson, a drag on productivity.22 In America, a 2014 Harvard Business Review paper argued credit was vital to small businesses, but the data on access was “troubling”.23 In May this year the US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau launched a request for information on small business lending. Both issues are key building blocks of prosperous economies.

Conclusion

Attacks on globalisation – and therefore, by definition, on free trade – are rooted in real concerns. For too long the political-corporate establishment has brushed under the carpet the very real damage being done to communities and individuals whose way of life is being steadily eroded.

The experience of NAFTA shows that free trade, alone, is not sufficient to raise all boats. But it also shows that free trade can generate wealth. The question for politicians and policymakers is what to do with that wealth. Protectionist policies will invariably lead to less prosperity. An effective state should divert some of the spoils of free trade into providing new skills and other forms of transitional assistance to those on the losing side of globalisation. That’s the real lesson from NAFTA… but it may be too much nuance for President Trump.

OPINION POLLING ON NAFTA…

A Pew Research poll from May of this year found that NAFTA was most popular in Canada with 74% thinking it had been good for the country and only 17% thinking it had been bad. By nearly two-to-one (60% to 33%) the 25 year-old Agreement was also reasonably popular in Mexico. In the US, however, NAFTA enjoyed the much narrower approval margin of 51% to 39%. Full polling here.

…AND FURTHER READING

James McBride and Mohammed Aly Sergie, NAFTA’s Economic Impact, Council on Foreign Relations, updated 24 January 2017

Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Cathleen Cimino and Tyler Moran, NAFTA at 20: Misleading Charges and Positive Achievements, Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 2014

Mark Weisbrot, Stephan Lefebvre and Joseph Sammut, ‘Did NAFTA help Mexico? An Assessment After 20 Years’, Center for Economic and Policy Research, February 2014

Gordon Hanson, ‘Why Isn’t Mexico Rich?’, Journal of Economic Literature, 2010

M. Ayhan Kose, Guy Meredith and Christopher Towe, ’How Has NAFTA Affected the Mexican Economy? Review and Evidence’, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, April 2004

Jorge Castañeda, ‘NAFTA’s mixed record’, The Council on Foreign Affairs, January/February 2014

Listen to Nigel Cameron talking about his new book, ‘Will robots take your job?’.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe