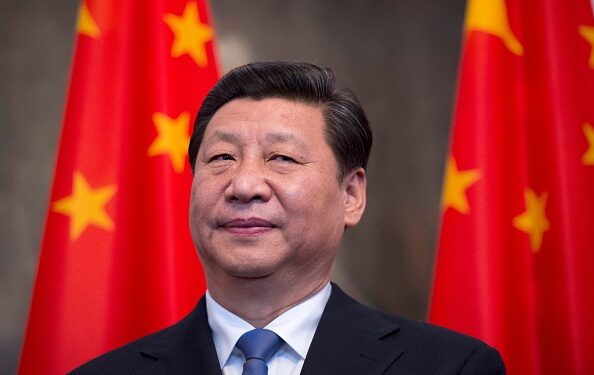

Xi Jinping isn’t worried about Trump 2.0. Photo: Johannes Eisele/Getty.

When Donald Trump increased the tariffs on Chinese goods to 20% last week, China’s Foreign Ministry blasted back that it was ready for a tariff war, a trade war, or “any other kind of war”. “China will fight to the end,” it added. But as startling as this might sound, the riposte was really rather mild by Chinese standards — boilerplate Foreign Ministry outrage. It certainly didn’t come across as realistic as Ontario premier Doug Ford’s threats to cut off the power to Minnesota as payback for tariffs on Canadian lumber.

For in truth, Beijing doesn’t seem all that concerned about Trump 2.0. An experienced China policy analyst told me a few days ago that Beijing’s political thinkers see Trump as “no worse than Joe Biden”. The Chinese public, likewise, seems genuinely relaxed about Trump’s return. According to recent polling from the European Council on Foreign Relations, 34% of the Chinese public welcomed Trump, and 21% didn’t feel strongly about him. (This would suggest that Trump is currently polling better in China than in California.)

Zhou Bo, former Senior Colonel in the People’s Liberation Army, and author of Should the World Fear China?, corroborated this view, telling me that most Chinese are not worried about Trump. “Compared with his attitude towards the rest of the world,” Zhou said, “[Trump] looks confusingly yet almost pleasantly ‘friendly’ towards China.” Zhou believes that Trump has learned from his first term that his signature unpredictability will not work as well on a peer competitor as it does on small or medium powers. Tariffs would be less effective too, as China moves toward a more self-sufficient economy. And compared to Trump’s first term, China’s economy is less dependent on America specifically. “So why should China worry?”

Another reason some Chinese are unfazed by Trump is that they believe his worldview opens up more space for China. The phrase “Trump founder of our nation” is bounding about a lot in China at the moment; the logic is that by distancing itself from its European and perhaps Asian partners, America is creating opportunities for China to exploit. German auto companies, for instance, might choose to partner with Chinese firms as America’s markets grow harder to access. America’s turn away from green tech is also opening up more space for China to sell solar and wind equipment to the Global South.

But that doesn’t mean the Chinese think badly of the US president. On the contrary, Trump is a familiar, and not unwelcome, figure in China’s social media ecology. “Looks like there’s a show to watch for the next four years,” said one Weibo user just after Trump’s election, in a post that was liked some 38,000 times. China’s “netizens” admittedly aren’t fans of his anti-Beijing rhetoric, although Trump’s kept that on a simmer rather than a boil since the inauguration. But nationalistic billionaires with strong opinions are now pretty commonplace in China, and that lot give Trump credit for his unashamed pro-American stance: China is not a place where bashful opinions about your own country gain much respect.

What’s more, many Chinese feel they’ve met Trump’s kind before, or at least, their parents have. One described Trump’s whiplash shifts in domestic policy to me as “the American Cultural Revolution”. The original Chinese version saw the supreme leader dismantle his own party from within, demand that people reject everything from the past as “old culture”, and empower 19-year-olds to lecture their elders about righteous political conduct. So far, no American federal employees have been made to take the “airplane position”, unlike those Chinese bureaucrats who were forced to stretch out their arms for hours on end. But plenty have been told that they’re the equivalent of the “cow demons” and “ghosts” targeted by Mao’s Red Guards. There has been no sign at all of the mass violence that scarred China’s major cities in 1966. Yet in China at least, there’s a sense that history is rhyming, if not repeating itself.

If there’s one element of Trump’s new regime that does worry some in Beijing, it’s the idea of a “reverse Nixon”, which has been floated in certain Washington circles. The theory goes that by getting closer to Russia, the US can force a peace on Ukraine, and then work with its new partners in Moscow to push back on Beijing. Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently gave an account on Breitbart of why it would be wise for the US to avoid confronting a firm Sino-Russian alliance, and argued that America should try to prevent that outcome by becoming closer to Russia. One Beijing thinktanker I spoke to buys into this idea strongly: he was at pains, privately, to say that the idea of “a friendship without limits” declared between Xi and Putin in 2022 is now old news, and that the partnership is pragmatic, not ideological.

Yet 2025 is not 1972. In that year, the USSR and China were in danger of going to war with each other, and had only the most rudimentary diplomatic relations. There wasn’t even a full Soviet ambassador in Beijing between 1964 and 1970. Nowadays, though, Xi and Putin seem to have worked out a genuinely cooperative relationship, and mistrust of Washington runs deep in both capitals. Even if Trump moves significantly closer to Russia in the next few years, analysts in Moscow and Beijing won’t forget that the next president might take exactly the opposite tack. Nor is it clear what material or strategic benefits would come to Russia if it turned its back on China. Falling out with the neighbours didn’t serve either Mao or Brezhnev well in the Sixties; Xi and Putin are unlikely to make the same mistake in the 2020s.

Another area of uncertainty is Taiwan. The pressure currently being placed on Ukraine to cede land to Russia is making some Taiwanese policymakers nervous — though they take heart from the fact that Trump’s national security team is full of China hawks, including Rubio and Waltz. Yet Trump’s Ukraine pivot won’t necessarily make a Chinese invasion of Taiwan more likely. An amphibious attack on the island would be difficult, regardless of policy in Washington. China’s other tactics may have a better chance of success, especially those of economic pressure, given 80% of the island’s firms are linked to the mainland, and social media disinformation, which could spread despondency about whether Taiwan can survive. The 2028 Taiwan presidential election campaign will see these tactics tested extensively.

For now, China’s policymakers have decided it’s better just to observe the Trump administration, rather than seek to influence it. But over time, as the new geopolitical landscape becomes clearer, the chance to shape “events not seen in a hundred years”, as Xi puts it, may become irresistible. Xi is referring here to the century since the Russian Revolution of 1917, which started the long breach between the US and China. As he bides his time, Xi will be calculating whether the new American Revolution provides an opportunity to reshape the global order in China’s interests — or even whether a grand bargain between the US and China might be on the horizon.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe