The news this week that Chinese Minister of National Defense Dong Jun is under investigation for corruption served as a clear indication that Xi Jinping is restructuring his military high command. Then, just a day later, came an announcement that Admiral Miao Hua, a fellow member of the Chinese Central Military Commission and head of the political work department in the People’s Liberation Army, had also been accused of “serious violations of discipline”. When one adds these cases to the purge which took place last year of key parts of the country’s army, culminating in Dong’s predecessor Li Shangfu being ousted last October, the process appears ever more cyclical.

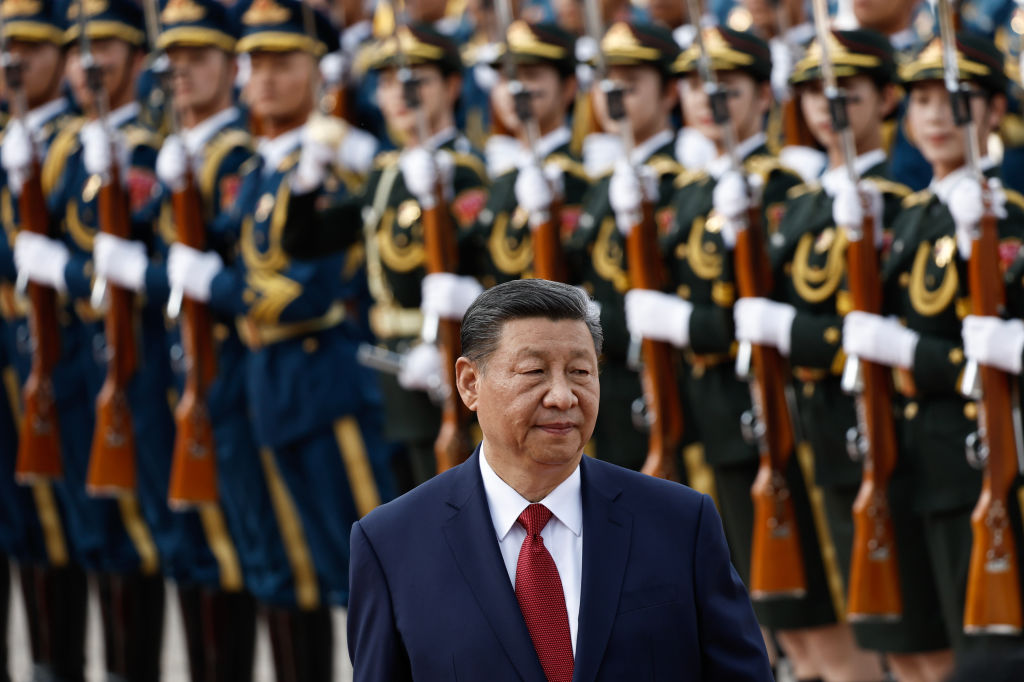

Why the need for this constant reshuffling of the upper ranks? The Red Army, since its foundation in 1927, has always been the military wing of the Chinese Communist Party: its loyalty lies there, rather than with the state. Historically, it provided the key power base for both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, a trump card to be produced whenever their power was challenged.

Xi worked in the military at the beginning of his career, before moving on to the civilian arm of government, and so carries direct knowledge of how China’s army works. But a new factor is the significant increase in the country’s military expenditure. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, in 2024 China’s overall budget for defence will reach a record $233 billion. While still some way behind the US, in real terms the resources available to Beijing’s soldiers and generals are massive.

The purges in recent years have usually centred on the parts of the military to which much of these resources have been devoted — in particular, a unit called the PLA Rocket Force. This has a broad remit to purchase and maintain both nuclear and conventional weapons, from Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles to standard bombing and launch equipment. This crucial arm has received the bulk of the state’s defence largesse, as well as being tasked with ensuring that China is ready to engage in regional wars to protect its interests in the coming decades.

Under Xi, the country is undergoing a more nationalistic and populist turn. But it is also highly aware of the volatile international situation. While often neglected by commentators, China’s domestic politics are profoundly influenced by external events, particularly in the US. Rising volatility in the Sino-American relationship since the first Donald Trump administration has made Xi’s leadership recognise the need to be prepared for any eventuality. The very actions the outside world considers signs of the country’s assertiveness are often a direct result of how China sees the pressures and threats arising from the international environment. It’s a vicious circle, and one with steadily rising risks.

The impact of this is both to upgrade China’s offensive capacity and to guarantee absolute loyalty among key military and administrative personnel. The problem in the army remains the same, however, as that which has historically plagued the Beijing government generally: personnel on relatively modest wages who are driven to temptation by the sizeable funds swishing around them.

Another purpose of these purges is to keep officials constantly on their toes, discouraging complacency and laziness. The continuous picking-off of those who, in the party’s eyes, have lacked either morality or political focus has been a key tool for ensuring discipline.

One side effect of all of this, as in the Mao period, is a general atmosphere of fear and trepidation within China’s air force, navy and army. The military has never been better funded, or had better equipment and capacity. But it has also never been exposed to such scrutiny and political attention. The question remains as to just how long these purges can continue before real opposition rears its head in the military.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe