A long list of reasons why the South African experience of Omicron would not necessarily be replicated in the UK was offered by high-status science commentators throughout December. The British population is older, less immune, the South African data is unreliable, etcetera. The claim was that, even though the wave had been much milder than Delta in a South African context, it could still be much worse in Europe and still overwhelm British hospitals.

Professor Neil Ferguson’s Imperial College team even produced a study, late in December, that managed to conclude there was ‘no evidence’ that Omicron was milder than Delta — based on the same theory that the differences in outcome could be entirely down to immunity rather than intrinsic to the virus. Patrick Vallance and Chris Whitty, the UK’s medical and scientific leaders, were persuaded and lobbied the Government for additional restrictions before Christmas based on the same apparent uncertainty.

And yet, once again, it turns out that the obvious was true after all.

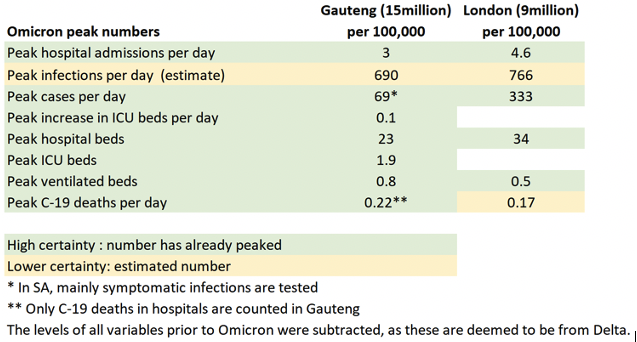

Now that the cases have peaked in London (since 23rd December in fact) and the hospital variables are in decline, it is possible to compare peak levels between London and Gauteng province in South Africa, where the Omicron wave began. There are very real differences between the two cities: Gauteng has relatively high prior infection levels and low vaccination rates, while London has lower prior infection rates and high vaccination rates. Gauteng has a younger population compared to London. Despite all this, the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) dropped 5-7-fold in both areas between Delta and Omicron.

Peak hospital admissions per day were slightly higher in London at 4.6/100k compared to 3/100k in Gauteng. Peak hospital beds were slightly higher in London at 34 beds/100k compared to 23 beds/100k in Gauteng. Due to poor quality public hospitals in Gauteng, many people in disadvantaged communities only go to hospital as a last resort, which partly explains the lower hospital numbers in Gauteng.

Infection levels were estimated to be similar in both metro areas. London does dramatically more testing than Gauteng, which explains the significantly higher case levels.

![]()

The peak in ventilated beds was lower in London at 0.5 beds/100k compared to 0.8 beds/100k in Gauteng. Peak Omicron deaths were also lower in London at 0.17/100k per day compared to 0.22/100k per day in Gauteng.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeShockingly SAGE were wrong again. When have they been right? These fraudsters have a stranglehold on Johnson and the government and it has for two years destroyed our country, it’s high time they go

Have you actually ever bothered to read the SAGE minutes or the data they use to inform their discussions ? From SAGE 99 Minutes 18 December

6. ” ….There are likely to be between 1,000 and 2,000 hospital admissions per day in England by the end of the year.”

Well not bad – running between 1,700 and 2,000 / day since December 30

I would recommend this also :

https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/reports/omicron_england/report_23_dec_2021.pdf (amended after Imperial Report #50) – produced by LSHTM and Stellenbosch Uni. and the basis for Omicron discussions in December. If you look at figure 2 column d at “Admissions” ( High immune escape, High booster effciency) you will see that the we are right now in the middle of the 50% quantile calculated by this particular set of assumptions.

If you look at the SAGE minutes for December 23 there are a long list of uncertainties :

and the final comment on these minutes ? :

“19. Booster vaccine rollout remains very important. Antiviral drugs will be particularly useful for vulnerable individuals.”

Deaths are now and have always been largely irrelevant. The really bad optics are those associated with not enough adequately staffed beds in hospitals both for Covid and non Covid patients because these directly affect the living and younger portion of the population – the result of a lean and mean NHS which has been like that for 10 years +

Considering we were at around 800 admissions a day when the meeting took place, quoting 1,000 to 2,000 figures for an event 2 weeks away is hardly scientific.

You are something else and really need your ethical compass adjusting: “deaths are now and have always been unimportant”. Are you kidding me. That’s the only thing that’s important. If there were no deaths and just increased hospitalizations nobody would have shut anything down, no citizen of any country would have stood for that, and even the UK and US governments wouldn’t have done a thing. the ONLY thing that counts is deaths.

All I can say is that this just confirms that everything you’ve ever said is way out of wack with reality. You are living in an alternative universe of the uninformed who claim to be knowledgeable but actually have minimal knowledge or training in matters scientific – and I’m afraid dentistry just doesn’t cut it.

Well said, and mentioning the list of uncertainties is a faux pas. With that list, no meaningful estimates could have been produced but they just went ahead nevertheless. Pathetic!

Not at all. You judge the plausible outcomes, and the related uncertainties, and then act on that basis. You do not just assume that you can wait till you have perfect information before you act. If I honestly have no idea whether there is a hungry tiger in the forest, the appropriate action is not to go for my regular evening walk every day until I am sure.

Again thanks, for knowing and providing the data. Unlike Johan Strauss, I really think we live on the same planet.

Yep, the mere mention of ferguson & his random number generator tells you all you meed to know.

What is equally bad is the promotion of questionable statistics by the media.

Yesterday it was stated on BBC that 150,000 people had died from Covid. That figure needs to be analysed because Covid was only “mentioned” on some of the death certificates and the fatalities occurred within 28 days of being diagnosed.

The only way to get the true figure is to compare the number of people who died of terminal illnesses from March 2019-2020 (cancer, heart attacks, strokes, diabetes, kidney or liver failure, Alzheimer’s (stop eating) and any other terminal illness that the Office of National Statistics might suggest.

Would they be allowed to give that information or is “the fear factor” still being promoted?

.

How is it possible that Sage continues it’s proclamations?

I just dont understand why the government is still tolerating this very-obviously-incompetent set of so-called experts. Doubtless they will defend their position on the basis of the precautionary principle, but their view amounts to destroying society just in case a few extra people might die of a disease that is more or less the same as flu.

It’s classic cut-off-your-head-to-cure-a-headache nonsense, and it is not acceptable for experts in any discipline to be making this mistake.

Check out the vanguard investment group: they are majority investors in many of the drug companies, and nearly all the Gafa’s, philip morris , etc etc

Quite right. It is man walking in front of car with a flag just in case thinking.

Yes the precautionary principle. These experts really need to get it together. The purpose of experts is to give wise advice, not to just predict the worst possible outcomes which are way overestimated. The analogy would be a woman going to a surgeon with a highly mobile breast lump and the surgeon proposing to do a radical mastectomy on the basis that the lump might be cancer, although any highly mobile breast lump is likely to be a fibroadenoma. Of course it should be excised, but a simple lumpectomy is more than sufficient. At every step of the game, right from the very beginning, the “Experts” have proposed measures equivalent to a completely unnecessary radical mastectomy. These “Experts” are not experts at all, but complete idiots with lots of credentials but not an ounce of common sense. And the same goes for the so-called US experts who are equally incompetent.

Similar people, operating in a similar way, are responsible for most climate bedwetting.

Model-based forecasts, group think, precautionary-principles and lefty virtue signalling. Recipe for disaster!

Labour wanted a lockdown (as I’m sure Boris will remind everyone today).

As did Sturgeon and Drakeford.

I don’t believe that’s right. Can you provide a link to backup your statement?

The reason they got it wrong is simple: they are not predicting anything, they are just selling us fear. They are a propaganda machine.

There’s also something desperately, desperately important here:

“Professor Neil Ferguson’s Imperial College team even produced a study, late in December, that managed to conclude there was ‘no evidence’ that Omicron was milder than Delta — based on the same theory that the differences in outcome could be entirely down to immunity rather than intrinsic to the virus.”

It was widely reported that the vaccination rates in SA were much lower than the UK BUT natural infection was much higher. .AKA They were happy to accept and report that natural infection produces long lasting, effective immunity from severe Covid19 disease in the Sars Cov2 virus. Let’s just accept this now and move on from 100% vaccination is the only answer to the end of the EMERGENCY.

This bristles with told you so hindsight.

I suggest it was more foresight than hindsight

What we are experiencing in Canada with Omicron suggests that the less severe waves in SA and UK may actually have more to do with natural immnity than anything else. We have the same or higher vaccination rates that the UK but our previous waves have been much less severe. I can’t help but wonder therefore whether our increasing hospitalizations (including amongst the vaccinated) are the result of less natural immunity? I have always wondered whether the prevlance of the spread in Europe was much higher than known/believed.

“Peak hospital admissions per day were slightly higher in London at 4.6/100k compared to 3/100k in Gauteng.”

Isn’t 4.6 50% higher than 3?

Shortly after COVID stared, Gupta published a number of model calculations, including one that proposed that COVID had already run through the population and the pandemic was effectively over. You will agree that was a complete mistake. Still, it does not disqualify her. On information available then, this was one possible senario (if maybe not the most likely one), and needed to be considered along with the rest.

SAGE made its predictions because they considered there was a significant risk that omicron would be more dangerous than hoped, and chose to plan for that eventuality instead of immediately jumping to the most optimistic conclusion possible. Only people convinced that they already know everything would do differently.

As a reasonable person if you repeatedly overestimate the impact of something then you realise your biases and adjust your settings so that your estimates are more realistic.

When a government institution does the same and the impacts of its mistakes are to crash the economy, ruin educations and cause a large number of excess deaths, what should that institution do?

Tom Chivers has covered his one. If a (let us say correct) calculation tells you there is a 10% chance of a very bad outcome, the sensible approach is to take measures to mitigate that outcome, in case. If it turns out it all goes well eight times in a row – as well it might – your approach would suggest to stop taking precautions. Then when the tenth time comes around, and you do get the very bad outcome – Ka-BOOM!

Your maths is pretty defective. A 1 in 10 has little chance of ever happening, not that it will occur every 10 occasion.

A 1 in 10 chance will happen on the average, 10% of the time. 10 cases in 100, 100 in 1000 is quite a big chance of ‘ever happening’. Sure, it will not happen ‘every tenth time’, that was a little sloppy. I just put it like that to make it clear that it will happen, and at about that frequency.

It all depends on the cost of the measures you take. If you take measures that are bound to increase deaths from postponed operations, increased poverty and depression your prudent measures may in fact not be so prudent. It is no good just considering what measures will mitigate worst case death projections that probably will not happen, the overall cost of the measures it is proposed to take need to be factored in.

But there was no evidence to support this belief, and lots of evidence to reject it.

We know why they did it, there’s no need to speculate. In the words of the head of SAGE modelling, models in which “decision makers” don’t have to “decide” things aren’t “interesting” i.e. the models are scientism used to justify and enforce the desired political outcome of big state interventionism. That’s it, that’s the end of it.

“But there was no evidence to support this belief, and lots of evidence to reject it.” There was overwhelming evidence to support this : Average age in SA 27.6 years (according to Worldometer). Average age in UK 40.4 years with an elderly bulge in the population (20% over the age of 65 compared with about 6% in this age group in SA)

Your risk of catching, becoming seriously ill and dying from covid increases 10,000 fold from 1 – 90 years of age with a big jump in risk of serious illness (requiring hospitalisation) and death around 65 – 70 years of age.

All irrelevant of course if the aim of the exercise (mismanaging the pandemic) is to cull the elderly population in high and middle income countries.

I suppose you could argue that such a policy (forbid access to hospital care and let them die outside) would be an efficient way of reducing the pension liabilities and strain on healthcare systems in these countries for a little while at least.

Of course lockdowns and the closing of economies, schools and companies has no effect on the population at all and we can just merrily print money to carry on with a UI supplement until the sun expands and swallows us all together, in a most equitable fashion.

So your solution to this conundrum would be what exactly ?

There is always a trade off.

Personally, with no restrictions, if the current numbers –

were the usual occurrence each winter for say the next 3 years for future Covid variants I would reckon that this would be just about manageable as far as the NHS / general optics were concerned.

Just for comparison purposes, in the really bad flu year (2017/18) admissions for confirmed flu peaked at 1000 / week (for just one week early in January) and total excess winter deaths (flu and everything else) was 50,000 covering the months December to March inclusive.

What would your cut offs be for a winter wave of Covid (discounting any extra burden through flu) ?

As usual you are talking out the back of your head, and the reality is that the facts on the ground have proved you wrong regarding Omicron. It was absolutely evident to anybody with half brain, some common sense, and perhaps some real medical, immunological and virological knowledge that Omicron was going to behave the same in the UK as in South Africa and that Omicron was basically nothing more than a bad common cold.

Get a grip Elaine, and perhaps retake a virology and immunology course 101.

What you have failed to understand right from the get go, judging from your comments, is that all the mitigation measures can do is broaden the peaks while leaving the area unaltered. i.e. they have minimal effect and the only thing they succeed in doing is prolonging the agony. The only proper public health policy to pursue is that advocated in the Great Barrington Declaration: .e. focussed protection of those most at risk while leaving everybody else to get on with their lives. And quite clearly, the one European country that did this, Sweden, faired very well, as did the various states in the US that did not impose restrictions, lockdowns or mask mandates. Moreover, had Johnson not got COVID, that is likely the policy that would have been pursued in the UK given that that was part of the pandemic preparedness plan.

You would do well to read the letter by Prof. Ehud Qimron, one of Israel’s top immunologists, to the Israeli Ministry of Health: https://swprs.org/professor-ehud-qimron-ministry-of-health-its-time-to-admit-failure/

Quite enlightening I think, and perhaps you will then understand exactly what is going on and the massive mistakes that have been made worldwide driven by unnecessary panic and hysteria.

Even just skimming the letter, it is easy to classify: evidence-free, paranoid rantings. Qimron may be one of Israels top immunologists. He might even be right in some of what he says, but the only thing you can get from his letter is that a certain Qimron feels very strongly about something. Nothing enlightening in that.

You are totally off here in your analysis because you fail to understand the art of medicine. As I pointed out above, you don’t go straight to a radical mastectomy for a woman presenting with a mobile breast lump on the basis of the precautionary principle. You do an excision biopsy and if the margins are clear or if the lump is not malignant (most likely if it’s mobile) that’s the end of the episode. Exactly the same applies to OVID and public health. The fact of the matter is that every single mitigation measure has had absolutely zero beneficial effect – all they have done is prolong the agony: the area under the curve has remained unaltered, just the width of the peaks has been broadened out a little. To what end. All it has done is wreck the lives of the least fortunate, led to innumerable deaths from other causes (cancer, heart disease, Cerebrovascular disease, etc…) which haven’t been treated, ruined the educational opportunities of our young, and turned us into a nation of complete wimps who are afraid of their own shadow. Truly pathetic, and as Robert Mallone pointed out, a very large fraction of the population is suffering from mass formation psychosis, including you Rasmus, judging from your comments past and present.

Yes!! You forgot to mention that the policies have led to an unprecedented reduction in the life quality for anyone living in a care home, the reduction of staff in the whole health & social care system and the transfer of land & wealth to the already wealthy.

It must be nice to live on your planet. Every single measure you disapprove of has had exactly zero beneficial effect and done enormous, obvious damage, and all the people who disagree with you suffer from mass psychosis and terminal stupidity. Good for your self-esteem, I am sure. But since I live on a different planet, we do not really have anything to discuss.

Perhaps we’d have something to discuss if you actually opened your eyes. Did the mitigation waves and their introduction prevent repeated waves – No; did the vaccines prevent repeated waves – No; Was tremendous damage done to the economy, the poor, children, the elderly living in care homes – Yes; has there been wide spread panic and hysteria – Yes.

Here’s the thing. At the beginning very little was known and it was quite reasonable to put strong measures in place until such time as more knowledge was gained and the true severity of SARS-CoV2 was really known. Once that was known and it clearly wasn’t anywhere near as severe as first anticipated, and the risk stratification varied dramatically with age, it was time to change course and adopt measures that might have been useful, including, as pointed out by Battacharya, Gupta and Kuhldorf, focussed protection of those most at risk. But was this done – No. What was done was theater rather than actually doing something useful. Those useful things would have included ensuring proper ventilation and air filtering in indoor spaces (easily achieved by some relatively high powered Hepa air purifiers at a cost of around $1000 a piece, and allowing early treatments. Now some of those early treatments may not have been very effective but their safety profile in terms of adverse reactions was very very high. But did our governments do that. No they made it next to impossible for doctors to prescribe early treatments at the onset of symptoms in the home. Yet in India where this was done, they had great success.

So open your eyes, read widely, inform yourself, and don’t be a sheep or poodle.

On my planet those early treatments (Ivermectin, presumably), were no better than placebo, as far as any available evidence is concerned. And people who put their trust in placebos without reliable evidence to back them up are very low on my reading list.

On your planet, the trials that were done were set up to fail. Just as Tamiflu (for the early treatment of influenza at the very onset of symptoms only) would have failed if tested under the same conditions. You have to administer those treatments very early before the virus gets down to your lower respiratory tract. Once the cytoine storm hits, there’s not much one can do as then you basically have a s**t storm.

Further, you also haven’t read widely. The meta-analyses on ivermectin are very good and show that it’s helpful. The recent trial of fluvoxamine in Brazil showed 90% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization. The administration of dexamethasone early on in the UK (in an Oxford trial) showed it to be highly effective in tampering the cytokine storm, and it doesn’t take much imagination or smarts to realize that one can extend that to early treatment by using either a butenoside inhaler or a course of prednisone way before ever needing to go to hospital. The clear cut correlation between COVID disease severity and vit D levels would have been easy to correct for in the general population – you would be amazed and just how many in the UK and US are vit D deficient with levels at or below 20 ng/ml, when you really need levels of between 50-75 for good innate immunity (as well as good bone health, especially in women).

So I may be low on your reading list, but as I have pointed out to you previously, I’m likely a good deal more knowledgeable about the subject than you are. And despite your knowledge of various mathematical techniques such as simulated annealing, you fail to understand that medicine is as much an art as a science. If one could just practice medicine by going through standard check lists, there would be no difference between good and bad doctors.

Incidentally, you would probably do well to look at your own medical behavior and that of others around you that you know, including your GP: I would bet that many of the treatments have not been subject to full blown randomized double blind controlled trials. Fortunate for the allies in WWII that there weren’t nay-sayers like yourself who would have insisted on not deploying penicillin to the troops because an RCT had not been done.

It is precisely because of people like you and their rigid, blinkered thinking, that much of the West has dung themselves into a massive hole that they are likely to clamber out of for years.

And lastly, you would be well advised to read the article by Dr. Alan Mordue, an actual Public Health Specialist (i.e. NHS consultant in this field for many many years) on how things have gone, and just how badly they have been messed up: https://dailysceptic.org/the-betrayal-of-public-health-during-the-covid-pandemic/

You two have been banging heads for some time now. You must by now realise Johan that no matter how much you write and explain it will be impossible to put a dent in Rasmus’s self confidence and beliefs written in stone. His devil’s advocate attitude seems to have run its course. I used to work with a guy with a similar approach and I decided it was better not to engage. It was just a waste of time.

Indeed, I am beginning to think something similar. People cannot agree on reality if they live on different planets.

Two problems, as I see it. First Strauss. He says, for instance, that it is proven that triple vaccinated people are more likely to get omicron than unvaccinated. Which would be a medical sensation. When EG-L sends a solid reference showing why this is not true, his reaction is to say that of course it is true and EG-L is, in summary, a retarded idiot. He does not even trouble to tell us what specifically is wrong with that article or its authors. If that is how he routinely deals with scientific evidence, nothing he says is likely to have any foundation.

Second, I guess, me. However many links I get from Strauss, I find they all have some things in common. They are from people who are extremely combative, who take it as a given fact that they are right and all official handling of the COVID pandemic has been obviously worthless, and who either do not provide links to reliable evidence or who refuse to engage with the arguments of their critics. No doubt, if I read widely and believed a lot of people like that I would gradually start to agree with Strauss. But I find such people totally unreliable and would not dream of taking on board what they say. And life is too short to seek out rubbish just to prove why it is wrong. To Strauss it seems to be important that you can find a lot of anti-lockdown fanatics with good scientific credentials. Personally I could not care less. Scientific evidence, and scientific debate for me, thank you very much. If what you say sounds wrong and has no proof behind it, it makes no difference that it is being said by a self-declared MD/PHD.

Well, you’re both combative and you’re still at it!

I’ve been trying to find articles which give more details on Covid and the vaccine than most people would bother looking for. Last night I found articles from a scientist who has submitted proposals to WHO. He seems very knowledgeable but for all I know he may be one of those who are instantly miscredited, Geert Vanden Bossche.

https://www.voiceforscienceandsolidarity.org/

To judge between Johan and yourself, Johan tends to give a lot more specific information in line with other sources I’ve checked out.

It’s got to the stage that when I listen to Swedish experts on vaccine and virology, I no longer believe what they’re saying in their simplistic and mainstream mesage. Nearly all of these figures being constantly brought into TV studios are financed indirectly by Big Pharma. I did find one on a rogue channel on Internet who broke the mould with detailed info on the vaccine, Ann-Cathrin Engwall, an apparent specialist in virology and immunology. The link is an interview in swedish.

https://www.vaken.se/hur-mrna-vaccin-dodar-celler-i-hjarta-och-hjarna/

Well, just a quick look. Geert Vanden Bossche has this at the top of his page: “Decision makers, in WHO, will be held responsible, accountable and liable for the dramatic consequence that this biological experiments on human beings could possibly entail.” Without being rude, this shows that he is a committed anti-vaccination activist. This does not prove that he is wrong, but it does mean that his opinion has no value as evidence – he would say that, as Mandy Rice-Davies said.

Ann-Cathrin Engwall is another story. She has documented experience of dealing with vaccine issues, and she writes like a scientist rather than an activist. And one important point she makes – sloppy research practices at one of the contract research companies responsible for testing the Pfizer vaccine – is supported by a solid reference.There are a couple of open question for me: How do the vaccine complications she quotes compare with complications from getting COVID, given that most of us are likely to get either one or the other, if not both? How much evidence is there that those vitamin/zinc cocktails actually help beyond placebo? What are the data for whole-virus vaccine or previous disease being better than spike-only or mRNA vaccines? In itself this only moves my opinion a little – there is only one of her and many on the other side – but it sounds like her arguments would at least be worth reading, and if I was pregnant it might inspire me to check available data more widely.

Elaine Giedrys-Leeper – sorry for freeloading on you – do you have anything that would add to this?

I did not get the impression that Geert Vanden Bossche is anti vax. He has had responsibility for Bill Gates’ vaccine promotion program. If anything, his vested interest is in future vaccines promoting NK cells, which to me as a layman sounded scary. I found his explanation of the workings and effect of mRNA vaccines to be plausible and a lot more detailed that what mainstream vaccine specialists are prepared to open their mouths on, eg. “the vaccine is safe”, “the vaccines give good protection”, etc. They’re still pumping out this diffuse narrative despite the evidence available, and I don’t mean the evidence which E G-L often refers to.

I did a bit of Googling and came up with some links here, here, and here. I would not claim that they are neutral either, but they show that there are some clear arguments against vanden Bossche. They also show that he has few and old publications, and that he has a brilliant and totally untested idea of his own for a completely new type of vaccine that he wants to promote. And, honestly, the idea that vaccines are going to drive the creation of new hyper-virulent strains that will kill all of us is completely speculative and rather weird. After all, it has not happened to the flu yet, has it?

Anyway, in combination with the apocalyptic tone of his posts – which is pretty much enough to disqualify him in itself – I think these links are enough for me to dismiss him. Of course the proper way would be to make a thorough scientific analysis of both den Bossche’s arguments and the counterarguments, but that requires more time and specialist knowledge than I can muster. Anyway, I leave it to you to decide what you want to make of him.

OK, I read it. Summary: an opinion piece.

I have no disagreement that the COVID pandemic was not treated in the way we normally treat epidemics – which would have amounted to patching the worst effects but generally letting it run. But on the main controversial points the article simply assumes that his version is right. No arguments, no information, no enlightenment. How likely are those prophylactic or early-treatment measures to actually be effective, and how do we know? Does it make scientific sense to insist that ‘there is no such thing as a asymptomatic case’, and what difference does it make anyway? Are false positives actually a problem – except for people who have a political interest in reducing the headline figures of case numbers? Do we have any actual numbers for the (undoubtedly real) ill effects of crowding out other types of patient, damages for lockdown, etc.? Can you trust his opinion on vitamin D, when the headline in his main reference effectively claims that vitamin D is the cure for COVID (“a Mortality Rate Close to Zero Could Theoretically Be Achieved”)? Et cetera …

Yet again, there is a person with good credentials who strongly agrees with you. Beyond that there are no arguments to convince anybody who does not already agree.

So are you denying the clear cut finding that there is a very high correlation that levels of vitamin D are correlated with bad outcomes? Clearly you are which is somewhat pig headed because one has absolutely nothing to lose by supplementing with vit D but everything to gain. Further, it is absolutely not a medical sensation that the triply vaccinated are 4.7x more likely to be infected by Omicron than the unvaccinated, and the doubly vaccinated are twice as likely to be infected. That data is right there in the UKHSA reports – yes reports from the UK government. It is also not very surprising if one knows anything about immunology and especially the well known and well-established concept of “Original Antigenic Sin”. i.e. the body first makes antibodies against the closest related antigen – but in this instance that antigen, the original spike, is no longer relevant, and those original antibodies bind poorly to the Omicron Spike protein. Further, it is also well known that poor antibodies can actually enhance susceptibility to infection. Indeed previous attempts at developing SARS-CoV1 vaccines found that all the ferrets died when challenged with the virus due to ADE. That possibility is a very real possibility and has been acknowledged as such by people like Fauci, even though it is now being put on the back burner so to speak.

Your problem is that you don’t want to actually use a scintilla of your god given intelligence to actually investigate the situation for yourself. Rather you are prepared to place full weight on the “Experts TM” who have proven wrong at every step of the current pandemic.

Your source does not give any reference to the correlation with VItamin D, so I cannot evaluate it, but there may quite likely be a correlation. Whether it means anything or is just a side effect of something else is another question – I’d look at a research paper making the claim, and compare it with the papers of those who do not believe it. But anyone who even suggests that high doses of a vitamin would actually cure COVID is making an amazing claim that needs extraordinary evidence or it should be rejected out of hand. And frankly – how many people have said that high doses of vitamins cure all kinds of ills? And when have they ever been proved right?

As for vaccination actually making the risk worse – you have thousands of professionals in different organisations the world over analysing available data to estimate vaccine effectiveness. The idea that every single of them is stupid or bought, and nobody is seeing a result that is obvious to anybody with an MD and internet access is really rather outlandish. If you had given me a link to the page and table you rely on (why leave me to flounder – surely you know it yourself) I could check your argument for sources of error. EG-L gave you a very convincing link why these data did not mean what you thought they mean, and you have still to comment on that – apart from insulting her.

Independently investigating the entire field from standing start would require a couple of years before I could conclude anything reliable – it is the equivalent of doing a new PhD. A quick Google search to look for something that seems to confirm your prior conclusions absolutely does not cut it. So I look at people making arguments, and check if they are making sense, if they are .linking to reliable data, and how they deal with counterarguments. And on all three counts you fall down miserably.