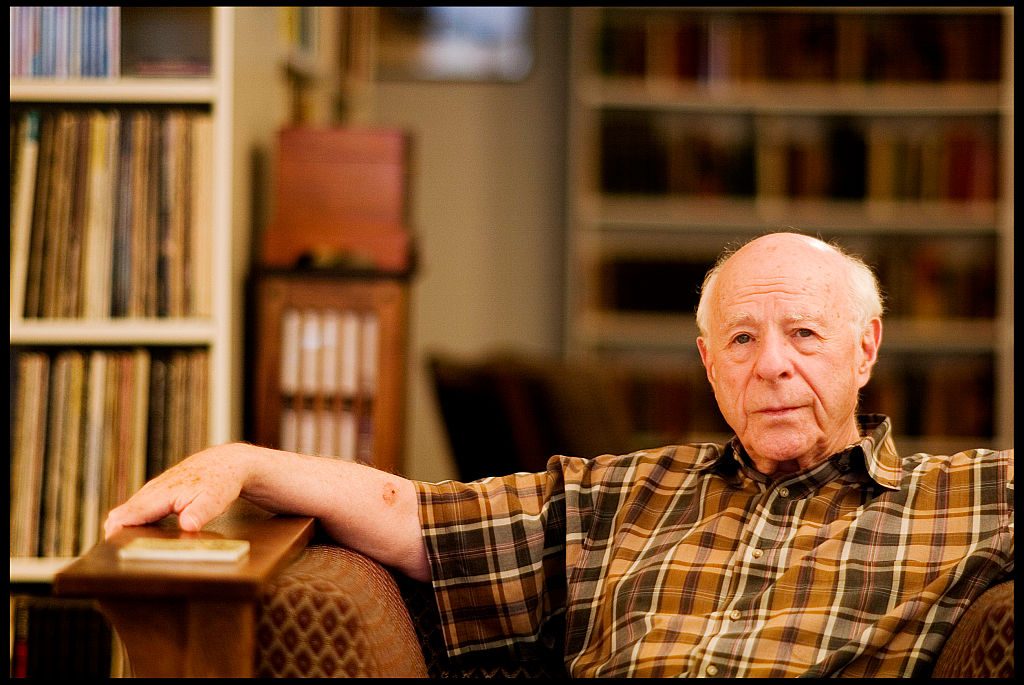

The American writer and editor Norman Podhoretz died yesterday, aged 95. He will be remembered as a towering figure in 20th-century intellectual life, as the master of a distinctly manly and forceful prose style, and as a model of fearlessness in defence of the things that matter most.

Podhoretz is best known as a founding father of neoconservatism, nowadays associated with the ill-fated Iraq War. But it is his astute treatment of America’s internal crises that will continue to offer important lessons in our time. Two closely related themes in particular stand out: his emphasis on a universalist American civic creed as the best means for bridging our differences, and his realism about what healing our racial fractures requires.

That first lesson — about the promise and necessity of a capacious American universalism — was hard-earned. He was born in 1930, in the Brownsville neighbourhood of Brooklyn, to working-class Jewish immigrant parents. It was a tough “ethnic” milieu, the kind many newcomers and even their children never rise above. But something in the young Podhoretz called him to something higher: to the life of the mind and the republic of letters.

Fortunately, he had the benefit of a Jewish tradition that cherished learning — and, crucially, public schools determined to draw boys (and increasingly girls) like Podhoretz into an American meritocratic mainstream. As the historian Christopher Lasch noted in his book The Culture of Narcissism, Podhoretz’s breakthrough 1967 memoir Making It is a testament to an education system that imparted a shared culture. In doing so, it then pulled immigrant children out of their respective parochialisms — into a higher sphere of cultivated judgement and engaged citizenship.

By the time Lasch was writing in the Seventies, that sort of education had become unfashionable and “multiculturalism” had begun to take hold. Yet, contrary to the multicultural dogma that schools should meet students “where they are” lest education erase difference, Podhoretz was in a sense liberated by a universalist education, without ever losing his grounding in Judaism.

From there, he was able to make “the longest journey in the world”, as he put it in the famous opening line of Making It: the one that had taken him from parochial Brooklyn to Columbia University and, soon, the commanding heights of Manhattan intellectual life as a longtime editor of Commentary magazine. Along the way, he changed his mind — most notably in shifting from the Left to the Right, hence the “neo” in neoconservatism — and converted many of his friends into ex-friends.

One particularly controversial moment came in 1963 with the publication of his Commentary essay “My Negro Problem — and Ours”, in which he recalled his tense relations, and occasionally violent run-ins, with black boys in his Brooklyn neighbourhood. It’s one of the all-time great American essays.

The headline and some of the language make for uncomfortable reading, even in our post-woke age. Yet Podhoretz’s ultimate insight was that racial harmony will come not with “tolerance” pablum, but instead with a sustained willingness to live side by side, remaining clear-eyed about tensions while looking to negotiate them politically and even domestically. He concluded the essay by speculating about a future age in which racial intermarriage will ease polarisation, a process which is unfolding today despite the protestations of more race-obsessed corners of the internet.

His later ultra-hawkishness — his post-9/11 book was World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism — clashes with the growing appetite for foreign-policy restraint on the American Right. Yet as the French saying goes, to understand everything is to forgive everything.

Podhoretz’s formative experiences — the curdling of socialism into Stalinism, the Holocaust and World War II, and then the twilight struggle against a soul-killing Soviet communism — urged him to a ferocious defence of the American democracy in which he’d found refuge and freedom, and which had allowed a boy from Brownsville to shape national debates.

As a former writer for Commentary, I’ve come to conclude that today’s greatest threats to the same cherished democracy are internal: America’s faltering cohesion and eye-watering material inequality. Yet in assessing Podhoretz’s legacy, that’s neither here nor there. His ferocity was finally a measure of his patriotism. May he rest in peace, and may his memory be for a blessing.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe