Support for euthanasia in the Netherlands is consistently high. It was the first country in the world to legalise the practice with the “Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act” in 2002. Criticism of the law from anti-assisted suicide campaigners are often seen as an attack on Dutch culture itself. But while the UK debates whether to legalise assisted suicide with Kim Leadbeater’s bill, a recent report shows a worrying expansion of the practice in the Netherlands to include psychological suffering and young people.

The report makes for startling reading. First, there are the numbers: almost 10,000 people were euthanised in 2024, a 10% rise from the previous year, and a significant number in a country of some 18 million people. Of more significant moral complexity, though, is the 60% rise in the number of those who were killed because of psychological suffering. In 2024, 219 cases were recorded, compared to just two cases as recently as in 2010. Of the 219, 30 were for patients aged 18-30. An unspecified number of minors were also euthanised.

Some of the cases detailed in the report make for hard reading. For example, an autistic boy between the ages of 16 and 18 asked for euthanasia on grounds of mental suffering, two years after he made an unsuccessful suicide attempt. The psychiatrists decided that his condition was untreatable, despite not having tried all available therapeutic models, and thought he might attempt suicide again if his application for euthanasia was not granted. A doctor also concluded that his wish to be euthanised did not stem from his autism but instead from the suffering caused by the consequences of autism, which some may consider a distinction without a difference. In any event, the request was approved, and the oversight committee praised the doctor for acting with caution and following protocol.

It is true that the boy’s autism would never have gone away, but at that young age one can hardly say with confidence that his ability to deal with it wouldn’t have improved. This is not to downplay his condition, but merely to state that it is impossible to know if someone’s misery is terminal, even if that is the most likely outcome.

In another case, an elderly woman who suffered from severe obsessive-compulsive disorder which manifested itself through a compulsive desire to clean was euthanised after suffering from a spinal fracture. Her injury meant she could no longer satisfy her cleaning urges. Her request was approved by doctors, who did not bother consulting a psychiatrist before making the decision. The case caused concern in the committee, which found that the doctor involved had breached the rules, declaring limply that “it expects a physician to exercise great caution when the euthanasia request arises from a mental disorder.”

Few have attempted to answer how increasing the availability of state-sanctioned euthanasia for psychological suffering can be squared with suicide prevention. Indeed, the former completely undermines the latter. Statistics show that legalisation of euthanasia does not reduce suicide rates. The figures show a modest increase in the suicide rate — excluding euthanasia — since euthanasia was introduced, and a rise in suicides among young people in the past decade.

The euthanasia committee’s chair expressed concerns about his body’s findings and called for debate about euthanasia for mental illness among young people. But it is unlikely that the law will be changed to exclude young people in mental distress. The previous Mark Rutte government also supported proposals to legalise euthanasia for sick children between the ages of one and 12 (it is already de facto legal for disabled newborns and permitted by legislation for children between the ages of 12 and 18).

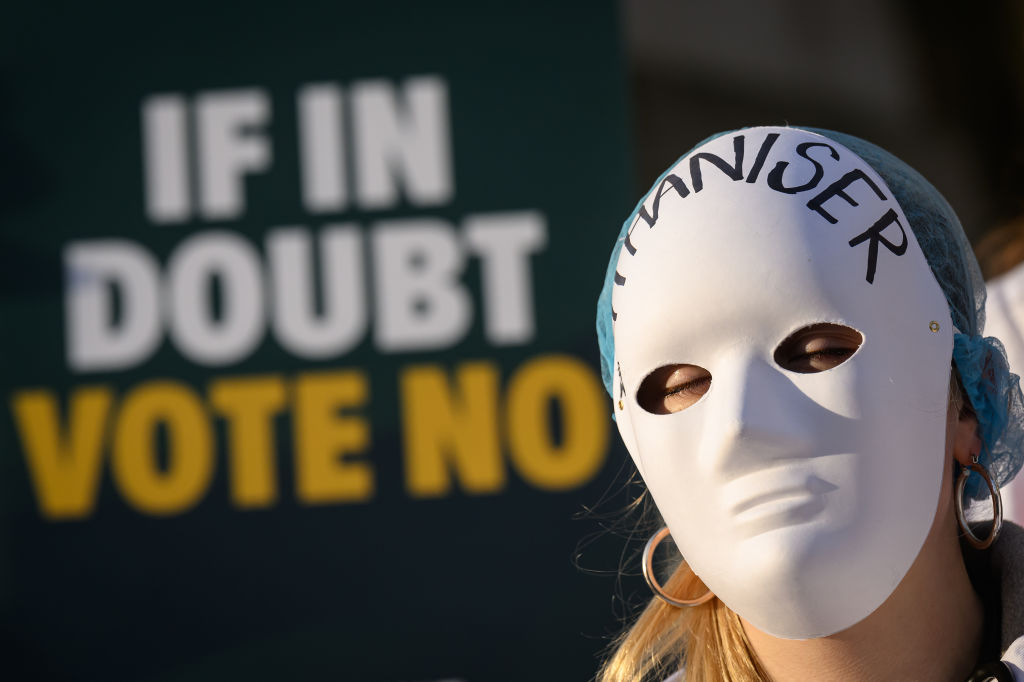

The Netherlands provides a bleak example of the ways in which euthanasia can be expanded. Legislators in other countries, particularly in Britain, should take note.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe