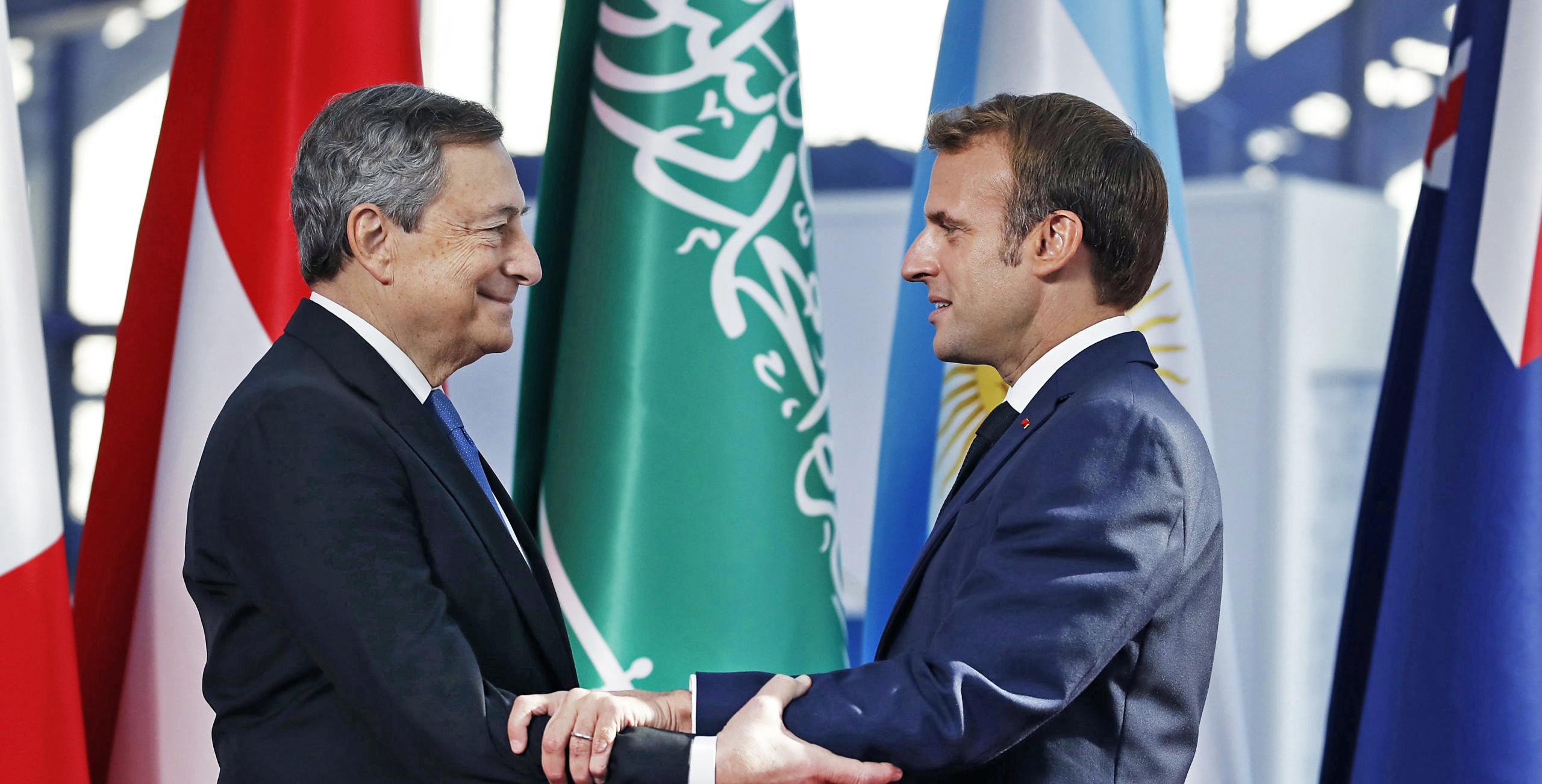

French president Emmanuel Macron will be in Rome today to sign an “enhanced cooperation treaty” — known as the Quirinale Treaty — between France and Italy. The problem is that, here in Italy, outside of Mario Draghi’s inner circle, no one knows the content of the treaty. That includes the Italian parliament, which will be called to rubber stamp the deal only after it’s been signed by the two leaders.

The whole thing is shrouded in the utmost secrecy. Indeed, most people weren’t even aware of the existence of such a deal until a few days ago. The little that we do know about the treaty is that Macron first suggested it in 2017, with talks starting in early 2018 with then-Italian prime minister Paolo Gentiloni, the current EU economy commissioner. The deal was then put on stand-by following the creation, later that year, of Italy’s “populist” coalition government between the Five Star Movement and the League, which clashed with France over several issues, from immigration to Libya to the Five Star Movement’s expression of support for the French yellow vest movement, Macron’s arch-enemy.

It was then revived under the second Conte government before it was fast-tracked under former ECB president Mario Draghi at the helm of government, earlier this year.

Given the recent history of French-Italian relations, which haven’t exactly been on an equal footing, the clandestine nature of this deal is not surprising. It’s an open secret that France has historically exhibited a rather predatory attitude, in economic terms, towards its southern neighbour. In the past 15 years alone, French corporations have bought out around 350 Italian companies for a total value of almost 50 billion euros. These include household names in fashion, food and financial sectors such as Bulgari, Fendi, Gucci, BNL, Galbani, Invernizzi, Locatelli and many others.

France’s latest masterstroke has been the creation of Stellantis, born from the fusion of France’s Groupe PSA with Fiat Chrysler, which has effectively put the Italian carmaker under French management. More recently, tensions have emerged surrounding a possible sale of a part of Italy’s defence giant Leonardo to Franco-German consortium KNDS.

No wonder, then, that last year an Italian parliamentary committee for national security even warned against “a growing and planned presence of economic and financial operators of French origin in our economy”, which could result in industrial decisions against national interests.

Meanwhile, France’s establishment hasn’t been especially forthcoming when its own national heavyweights have been at stake: in 2017, when the Italian Fincantieri won the tenders for the majority of the French shipyard STX, Macron ripped up the tenders and temporarily nationalised the company to stop it from falling into Italian hands. This episode is revealing of the French establishment’s zeal in defending its national interest — a zeal that is all but absent in its Italian counterpart.

Italian politicians are not new to this kind of servile attitude towards France. That several of the most prominent members of the Democratic Party (PD) — including its current secretary, Enrico Letta — have been awarded the Legion of Honour, the highest French order of merit, is telling. Indeed, Letta — dubbed “the Frenchman” by his critics — also has (had) stakes in several French companies.

In light of the above, many people question what the consequences of the treaty for Italian industry will be. But even on other issues, such as foreign policy (take Libya) and immigration, the two countries’ interests have often been divergent, if not outright conflicting. It thus seems highly unlikely that the treaty will give rise to a new French-Italian axis capable of acting “in the common interest” of the two countries and maybe even rebalancing German hegemony in Europe, as some commentators have argued.

It appears much more likely, given the power relations between the two countries, that the treaty will simply serve to entrench Italy’s subsumption into France’s sphere of influence, and further erode what little sovereignty Italy has left. As Roberto Napoletano, former editor of the Italian business newspaper Sole 24 Ore, wrote in 2017: “In international circles, the prevailing political reasoning takes for granted that the French want to conquer the north of Italy and perhaps let the south become a large tent city for immigrants from all over the world”. There’s no reason to believe that has changed.

Update: the draft of the deal has now been published.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe