Since Canada’s euthanasia regime broke into the global public consciousness earlier this year, people across the world have been horrified by stories of ordinary Canadians choosing to die at the hands of a doctor instead of carrying on living in poverty, of disabled Canadians told to kill themselves by bureaucrats, and of plans to extend euthanasia access to the mentally ill and to “mature minors”.

But until now, defenders of Canada’s MAiD (medical assistance in dying) regime have pushed back aggressively, accusing their critics of spreading disinformation, or worse. They hide behind the fact that poverty is not in and of itself a legal ground for accessing euthanasia, or else claim that the cases of abuse reported in the media are outliers. And because of the opacity that naturally comes with the medicalised rituals of death, it has been difficult for outsiders to know exactly what goes on between the doctor’s office and the funeral home.

Now we know more. Alexander Raikin, a writer based in Washington D.C., has unearthed a cache of publicly accessible but hitherto unreported training material created by the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP), an umbrella group for the medical professionals involved in the peculiar process of providing death. This material, a small portion of which was recently published in an American magazine, The New Atlantis, reveals that those self-appointed guardians of life and death knew all along that many of the public defences for the practice were untrue.

CAMAP, a charity, has no official regulatory role under Canadian law for the provision of assisted suicide. Nevertheless, it has established itself as the de facto standard-setter for euthanasia providers in the country. In July this year, Canada’s federal health ministry announced that it would outsource assisted suicide training to CAMAP, along with a $3.3 million grant.

In public, its leaders deny that there is anything wrong with Canada’s euthanasia regime. Its head, Dr Stefanie Green, has performed more than 300 euthanasia procedures and says “the act of offering the option of an assisted death is one of the most therapeutic things we do”. She is a vocal defender of the practice: in an interview, she said that “you cannot access MAiD in this country because you can’t get housing. That is clickbait. These stories have not been reported fully”.

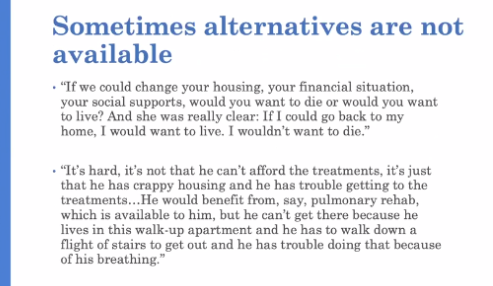

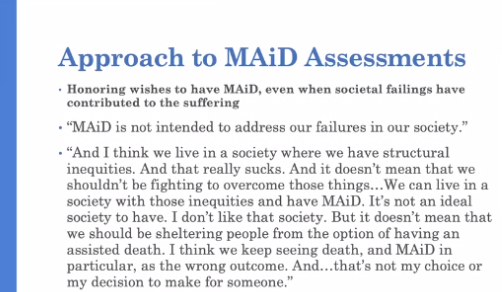

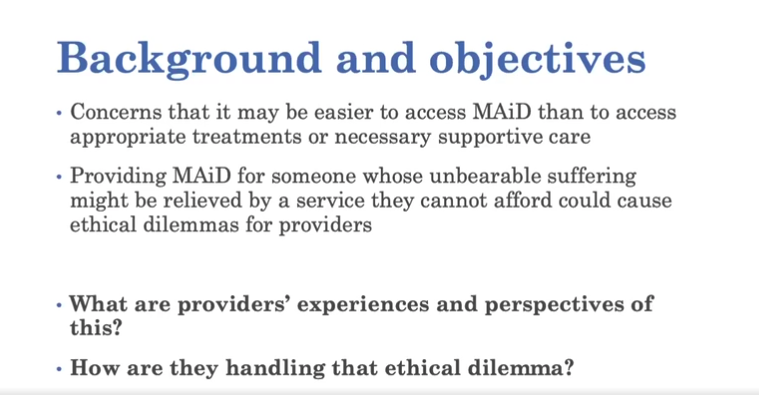

But her organisation’s internal training seminars tell an entirely different story. In a seminar tellingly titled “Accessing Alternatives to MAiD: What is the role of the MAiD Assessor when resources are inadequate?”, Althea Gibb-Carsley, a recently retired MAiD professional in Vancouver, documents several real-life cases of patients who have sought to die because of a lack of housing or of other resources.

One 55-year-old woman who sought to die “identifies poverty as the driver of her MAiD request – food insufficiency and inability to access appropriate treatments”. The slide (above) points out that “what she really needs” is “an extra $600 or so /month”. Another patient, a 57-year-old man and published author, identified lack of housing and lack of access to medical care among the reasons for his request to die. He had been told that obtaining social housing would take between three and six years; he planned to “stretch credit to the edges then […] set final date” for his death.

Although similar to stories already reported in the Canadian press, these cases are noteworthy because they have been documented by Canadian euthanasia providers themselves, despite their well-trodden public line that such things did not happen in real life.

Nor is this the only area in which euthanasia providers’ public position differs from their private one. For instance, MAiD providers have been at pains to emphasise the rigorous nature of Canada’s procedural safeguards for euthanasia. On paper, they seem adequate: each demand has to be assessed and approved by two medical doctors or nurse practitioners.

What euthanasia providers don’t say out loud is that a patient who is turned down by one assessor can simply “doctor shop” for another one until a willing assessor is found. In another CAMAP seminar, Dr Ellen Wiebe describes a case of a man who was rejected by a MAiD assessor for the procedure because, as Raikin writes, “he did not have a serious illness or the ‘capacity to make informed decisions about his own personal health.'”

But a pro-euthanasia group connected him with Dr Wiebe, a prominent MAiD supporter who was previously accused by a Vancouver Jewish nursing home of sneaking in to euthanise one of its patients (to which she admitted; the provincial medical regulator cleared her of wrongdoing). As she recounts, she performed an assessment online, found him eligible, found another assessor who agreed with her, and drove him from the airport to her clinic, where she “provided for him” or, in other words, ended his life.

All this was legal since, according to yet another speaker, law professor Jocelyn Downie, doctors “can ask as many clinicians as you want or need”. “There is no certainty or unanimity required. There is no perfection required”. As Raikin puts it, “There are many paths available to reach the end, and you only need to find one. The system makes it easy to die.”

This is only the tip of the iceberg. Raikin, who has collected two years’ worth of such training sessions and personally interviewed many of the protagonists, has shared with me details of many other shocking instances where MAiD providers admit in private what they strenuously deny in public.

Meanwhile, participants of these seminars continue to shape the public debate over euthanasia, using their status as ostensible experts to do so. Professor Downie, who told euthanasia providers that they can “ask as many clinicians as you want or need”, has just criticised the Canadian government for seeking to delay the introduction of MAiD for mental disorders because “she does not think a delay is the right decision from a legal and clinical perspective”. How easy should it be for someone to die? Downie does not say.

We implicitly trust our doctors with our lives; but what happens to their profession’s moral guardrails when they are entrusted with the task of killing instead of curing? We are beginning to find out.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe