The influence of Left-wing identity politics on the media is beyond doubt. That’s not an opinion, but a quantifiable fact. By counting the number of times that relevant terminology like “whiteness”, “male privilege” and “cultural appropriation” is used in mainstream publications like the New York Times, one can chart an explosion of coverage over the last decade.

However, this isn’t just happening in the media. A new report from the Center for the Study of Partnership and Ideology (CSPI) looks at an area one would hope would be free from ideological influence: scientific research.

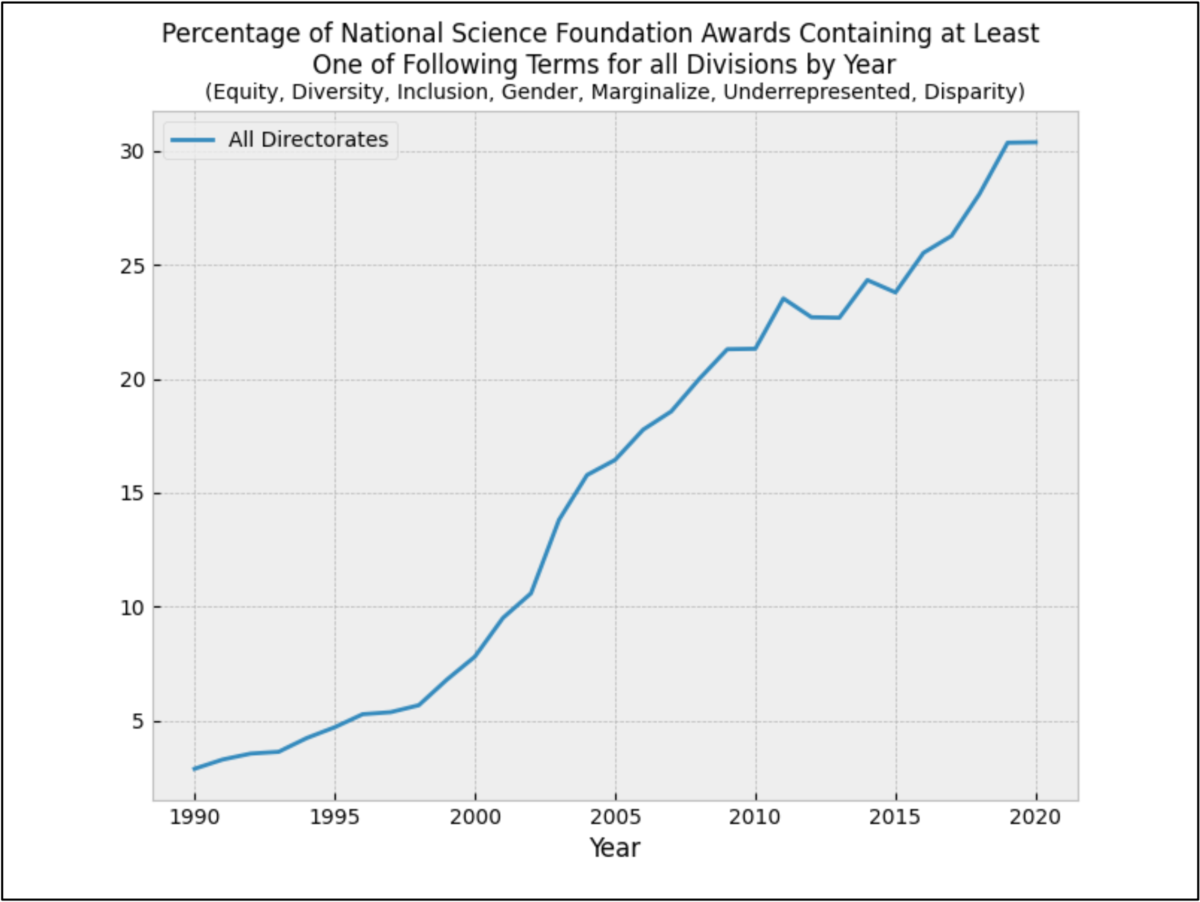

The report’s author, Leif Rasmussen, uses natural language processing to analyse the abstracts of successful grant proposals to the National Science Foundation — the main grant giving body for scientific research in the US.

This is the key finding:

That’s a big change, but is it necessarily a bad thing? Though the CSPI describes the overall trend as “politicisation”, one could argue that science can remain objective while being made more relevant to the lives of previously marginalised communities. Scientists should also address specific issues such as the underrepresentation of certain groups in medical trials, which can lead to an incomplete understanding of the effectiveness and side-effects of treatments.

If researchers are wording their grant proposals to reflect a genuine and useful effort to make science more inclusive, then that could be counted as a positive trend. However, the CSPI research also finds a marked and recent uptick in the use of overtly ideological language like “intersectional” and “Latinx”.

Another potentially worrying trend identified in the report is an “increase in similarity between documents that is particularly pronounced beginning in 2017.” In other words, the language used in grant proposals is becoming less distinctive. Why would that be? Politicisation might be one explanation, but it could just be that scientists are generally getting better at wording proposals to tick the boxes of the grant-giving bureaucracy.

Whatever the reason, we should be wary about any trend towards groupthink. Though we certainly don’t need any old or new form of pseudo-science, the progress of actual science still depends on the ability to push beyond the established consensus.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe trouble is, much of modern science is groupthink.

Taking the groupthink out of climate science would be like taking the pasta out of spaghetti.

They call it consensus, to make it sound like there’s been a discussion, but that’s what it is.

Sorry, but this is ‘Heads-I-win-tails-you-lose’. If there had been lots of disagreement and contrary opinions, that would be taken as proof that climate science is unsettled and any conclusions are unreliable. As there is close to a consensus, that is taken as proof that there has been no proper discussion and any conclusions are unreliable.

This is not the first time that science has moved to consensus on a controversial subject – and it is not the first tiem the losers cry foul either. It may not be straightforward or pretty, but it is the same approach that brought the germ theory, evolution, etc.

You should be careful here because it is not that evident that there is a consensus for those really in the know, as opposed to the many who tow the “party line” without really knowing anything. at the very least, anybody with a minimal amount of common sense should realize that computer modeling of complex processes where there are not only many known unknowns but many unknown unknown is fraught with error. This should have been made abundantly clear during COVID where every model has proven to be widely off the mark but yet has been slavishly used by public health officials claiming they are following “the science” when in fact they are following nothing more than voodoo. Thus, with regard to Climate, anybody who thinks that one can accurately predict what the climate will be in 50, 75 or 100 years is quite simply not scientific and for anybody who believes the results of the modeling I’ve got beach front property to sell them in Nebraska!

To me the climate consensus looks about the same as the scientific consensus on so many other things. The one difference might be that there is a strong lobby group wanting to dismiss the results, much as there was for smoking causing lung cancer, If anything there is much more careful attention to uncertainties and prediction intervals – as there ought to be for something with so big economic consequences. Limiting your evaluation to those ‘really in the know’ can be a bit of a trap as well – at least it can be a handy mechanism for packing your jury.

For the rest, ‘All models are wrong – but some are useful’. You do not need accurate 100-year predictions to draw useful conclusions. CO2 *is* increasing; this *is* caused by human action, this *will* (by well understood basic physics) heat up the planet, and it will cause things like melted glaciers, higher sea levels, changes in rainfall, which crops can grow where etc. Exactly how much heating and how big those changes are (manageable or terrible) and what low-probability-high-damage events might happen is a lot less certain. Still, I refer to Tom Chivers on how you should deal with high-damage, medium-low-probability events. Waiting till you are certain (and it is too late to avoid them) may not be the best plan.

We know that the “consensus” trope is a red herring because there isn’t even a consensus on what the consensus is. Tell us, Rasmus, for what conclusions are there a consensus?

Here is the real problem. The mathematical models used to predict the future are so complex that I doubt anyone on UnHerd can understand them. Also somebody has to choose which data to use and which data not to use so there is also a human input.

This makes the whole thing impossible to argue properly. However, certainly the politicians don’t understand what is going on and they are making bold decisions which will affect many generations to come. Nobody is really qualified to make these decisions. It seems to me that there is nowhere near a consensus on the matter – it is even possible that we will make things worse by our actions.

However, there can be no argument about certain things. Cutting down trees doesn’t sound right and the rich nations could easily bribe countries to police this properly. Plastic packaging has to be stopped. Again, this might require bribes.

It is not quite impossible, just hard, and anyway the decisions have to be made (or ducked). But by and large I agree with you.

I predict that efforts to manage the sky will be hugely costly, wasteful, and ineffective, and will be abandoned after they have destroyed enormous wealth. All these initiatives will very obviously fail and thus the obvious course is to mitigate from deeper pockets in 100 years’ time. If it is even necessary, of course (I suspect not; warm periods in the past have always been prosperous).

I’m quite willing to accept that CO2 is a greenhouse gas i.e. it has insulation properties. That’s not because I’m a scientist, it’s because it must be easily provable or disprovable in controlled laboratory experiments.

I’m equally willing to accept that the human race is pumping much more CO2 into the atmosphere than it ever did before. Again not because I’m a scientist but because I live near a city and drive past coal-fired power stations.

I’m less sure we can accurately measure that in parts per million, but let’s ignore that.

So we have two indisputable facts. We’re emitting more co2 and it’s a greenhouse gas – settled science.

Everything after that is prediction. It would certainly be intuitive to assume increasing greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere will warm the planet, but I think any scientist that claimed, on the basis of two facts, that he could be certain of a causal relationship, impacted by literally millions of other interactive elements, would be accused of ludicrous hubris.

And yet not only do we draw that straightforward causal relationship, we go further to say that we can model these millions of variables to predict not only how much the temperature will rise, but what the global impacts will be on sea levels and a myriad of other weather events.

Modelling isn’t science.As John says, the multiplicity of known and unknown variables means this simply cannot be settled. If we’re not hearing voices disputing it then that must be deliberate.

It’s worth having a look at the IPCC report. It‘s easily found on google and has thousands of pages of high, low and medium probability projections based on varying probabilities of other things happening. The entire thing is an exercise in imprecision. Yet we’re expected to believe relentlessly apocalyptic, and quite precise, projections delivered as fact.

I don’t really go in for “Davos elites manipulating us all” type conspiracy theories, but it does appear to me there’s a relationship with money.

It is now the advanced countries that are picking up on this.That is the countries with the R&D facilities, technological capability and manufacturing infrastructure to be ahead of the curve in a new technology industrial revolution. Even countries that are slightly behind the curve, China and India come to mind, know they are getting there and are only fighting a delaying action. Those that have no chance of benefiting from it, are just demanding compensation.

The real problem isn’t global warming. It’s a huge number of environmental degradation impacts, from plastic pollution through overgrazing, deforestation etc etc. Easier to identify, less money and more political risk in fixing.

That all sounds fairly reasonable. I do think we can go further than you say, though. The CO2 concentration in ppm has actually been measured, since 1958, in Hawaii. And the effect of adding CO2 to the current atmosphere while keeping everything else constant should be calculable – it is straightforward physics applied to a fixed framework. It is when you get into all the knock-on effects that influence each other, feed-back loops etc,. it gets ever more speculative. But the ‘high, low and medium probability projections’ are actually *exactly* how you need to work when you are dealing with uncertainty. You cannot be sure, so you need to allow for lots of different scenarios with appropriate probabilities, and end up with a probability distribution of outcomes. This is not where you want to be, of course, but it is an honest attempt and anyway the best that can be done. The hard thing is to get to a sensible decision when you have nothing better than that – but you could argue that pension funds and central banks are no better off, and they manage to decide somehow.

There is no doubt that companies are going for getting rich off the transformation, but we should remember that there is money on the other side too. Between Saudi Arabia, Australia, the oil companies, the Chinese coal industry – and Pennsylvania – that is a lot of money and power. Certainly enough to finance some big research projects. If nobody has come up with a convincing scientific case why global warming is not going to happen – and you can bet that people have tried – it is probably because such a case cannot be made.

A “consensus” that’s subject to attacks is not one.

You are absolutely correct when you say it is not evident that there is a consensus for those really in the know, as opposed to the many who tow the “party line” without really knowing anything.

When I hear the oft quoted “XXX thousands of scientists agree that anthropogenic global warming is real and an immediate threat to humanity”, I know that I am included twice in those XXX thousands of scientists because both of the institutions of which I am a member have pledged their support to such statements. Neither of these institutions has asked me whether I agree; that support was submitted on my behalf by the administrators that run the institutions. Furthermore, atmospheric chemistry is way outside of my specialist field, and outside of the specialist field of almost all others in those institutes of which I am a member. Our opinion is worth no more than any other member of the public. I suspect that, at most, there are maybe a few hundred scientists globally who understand atmospheric chemistry in sufficient detail to give a robust professional opinion and, even then, there would not be a consensus of opinion.

Why do these institutions pledge their commitment to the environmental cause? It’s because the administrators of those institutions spend their time and effort on public engagement, policy development and briefing Government departments and have long ago drifted away from doing front-line science. To do their job, at the interface between science and Govt policy / public opinion, they have to adapt their views to fit in with the current political zeitgeist. They have to do this because their institution and / or the major employers in their particular field depend on Government funding or Government contracts.

This all happened years ago with respect to the climate change agenda. The same is happening now with all other woke issues. If you want funding for your science, you’ve got to get woke.

Absolutely spot on, and my observation as well.

Eugenics is an earlier example of a scientific consensus. It unsurprisingly fell out of favour after WW2. The politicisation of climate science was as inevitable as that of genetic selection. I would like to see this rolled back but, as you rightly say, there are too many vested interests in academia, big government and commerce for that to happen. I believe that only climate scientists themselves could achieve a retrenchment to a purer science and they’re not about to do it.

The use of the hyperbolic word ‘voodoo’ rather weakens your argument. It is absurd to object to models ‘per se’ – when practically every government department and large business uses them – for example governments depend heavily on economic and population models. Their strength however depends on how robust are the always necessary assumptions that are input.

There is no serious doubt, that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, and that global temperatures are warming. Most climate scientists do consider that man-made emissions are significantly or largely contributing to this, others are not convinced that in this case correlation means causation. I am a genuine sceptic in the genuine sense of the word, not someone who would never be convinced by any amount of evidence, as it seems are too many people on here.

Nope. There’s a consensus that penicillin kills bacteria, but it’s not one arrived at by suppressing dissenting opinions. It’s based on hard observations, repeatable studies and real-world experience. The argument that penicillin kills bacteria is not that there’s a consensus that it does. It’s that there’s evidence that it does.

None of this is true of climate science. In fact, it meets the definition of a pseudoscience:

…characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited.

The goal of climate science is to show that humans are harmful. Anything that challenges this is automatically inadmissible as climate science. As Professor Phil Jones memorably put it, “I will keep them out somehow – even if we have to redefine what the peer-reviewed literature is!”

well said Jon & John

The problem with that view is ‘Who decides what is evidence’, ‘who decides what to believe’? And the discovery of antibiotics is about the only, single, unique case in medicine where the conclusion is obvious straight away.By that standard most modern science would fail.

There are always people who find a reason to dismiss the evidence and come up with an alternative explanation. Eventually the mainstream ignores them and moves on, and they do not appear in the next generation of textbooks. That, too, is science.

the evidence itself decides if its convincing or not, a knife in the back covered in fingerprints, eye witnesses and signed confession are pretty convincing evidence. a computer model of the climate made by people with an agenda that just so happens to “prove” their climate change theory and necessitate more grant money for themselves, not so convincing. These “climate scientists” can’t predict tomorrows weather, why would i place trust in the “evidence” of their predictions 100 years from now?

The ‘tomorrow’s weather’ argument doesn’t really score any points – future climate states are not simply the cumulative expression of a few thousand tomorrows. We all bet that our pension investments will work out in the long term, but accept that we can’t forecast what will happen to any one stock tomorrow.

Andrew, future climate states can only be the cumulative expression of a few thousand tomorrows. what else could they be?

so rather than a slam dunk, your pithy line looks like a dodge. my point is if climate modelling cannot make an accurate 1 day prediction based on all current variables being known to them, then in what world is climate modelling based on unknown variables 100 years from now in the future to be considered reliable?

or as Peterson might put it maybe climate scientists should tidy their room first before trying to change the world.

Ok, not well expressed. What I’m getting at is that trends in large systems can be modelled well enough over reasonable periods, or at least well enough for us to take a view, say, on when to plant the potatoes or whether to dig a well. That’s not contradicted by the inability to hit 100% accuracy on tomorrow’s rainfall in mm.

Future climate states are a function of natural atmospheric trends, affected to an unknowable extent by the future human population, future technologies, and the future cost and source of energy.

All three of the latter are unknowable. Conclusions based on crude models that guess at what they might be are have no value.

The entire field of climate science is fundamentally worthless. It will go the way of alchemy; the question is how much damage it can do before it is rumbled.

You have picked the right word: bet. Otherwise called gambling.

Exactly my point.

This is right. The distinction that should be made – but which is seemingly not – is between modelling which can be tested against physical experiment, and modelling which cannot be so tested. For example, fluid dynamics is an example of the former, and we can now have high confidence in, say, modelling of aerodynamics. Epidemiology and climate are areas where we cannot test, and hence confidence in such models is misplaced.

“Sorry, but this is ‘Heads-I-win-tails-you-lose’.”

No it isn’t. What decides this issue is the evidence, not the size or character of a consensus around uncertainty about that evidence. The fact is that climate science has not delivered any actual proof of the most controversial parts of the political consensus, and this is true whether or not a guesswork-consensus exists in climate science or not.

Your objection here is entirely specious.

You do realise that the only way to generate proof would be to wait 50 or 100 years and see if the catastrophe had occurred? In short you are saying that we should never consider what to do about future climate, because it is too hard and off limits?

100 years ago, apocalyptic nutters held up signs saying the end is nigh on street corners. Today their inheritors glue themselves to motorways. Your welcome to sympathise with them Rasmus, but it doesn’t mean there is any more evidence behind these claims than 100 years ago.

“You do realise that the only way to generate proof would be to wait 50 or 100 years and see if the catastrophe had occurred?”

Once again you are wrong. There are lots of ways the alarmist version of the theory of global warming could be proved, in much the same way that the theory of evolution is proved: a set of theoretical ideas combined with observation and experimentation which builds a coherent explanatory framework that excludes all competing hypotheses. That is why we believe the theory of evolution, not because of empirical observation.

The alarmist theory of global warming however, fails such tests whenever they are attempted, because everything we discover observationally is more consistent with the idea that rising atmospheric CO2 does not and will not cause a dangerous warming effect. If you still want to maintain that even the smallest danger that it might, justifies the colossally expensive and regressive plan to address the problem, you must also explain why we’re squandering a century’s worth of progress on that and not, say, an asteroid defence shield, or a brand new energy network that’s resistant to solar flares.

Sorry, but it fails every rational test, and only passes the political test because there’s something in it for a certain brand of politics. If you want to adhere to that politics that’s your business, but you don’t get to call it science, because it’s not.

That is not the mainstream opinion. I wonder who you chose to rely on for that belief.

Rasmus, pal, your not really making much sense on this topic, is it evidence that determines the truth of climate change or the popularity of the opinion?

If John Riordan has personally read and analysed all the data and happens to be the worlds topmost climate expert, I should like to see his credentials – and his data and reasoning. If he is not, I should like to see what his reference is for making such categorical statements. Personally I do not know all the data and could not analyse them myself anyway, so I have to rely on who to trust, At most I can do some limited checking for what makes sense.

The evidence does not talk, and the fact that people can disagree shows that the conclusion does not follow automatically. Actual people have to weigh the evidence and decide what it means. Next, even top experts need to check their conclusions against what they can convince other experts to believe, to guard against their own mistakes. You cannot get around depending on people (even if they are sometimes wrong), but science works in the end as long as people are honestly trying to find the truth and listen to argument – eventually the right result will come out.

thanks for responding Rasmus, like Galeti said this place is better for having you in it.

I agree with pretty much everything you say in the above post, where we differ I guess is I have no trust in the credentialed climate scientists from the first step so all that follows from them I don’t trust either. I could be instantly convinced with an experiment that showed CO2 is the determining factor, but i can remember a time when all climate scientists funding depended on, and their consensus was that, the hole in the Ozone layer was the cause (of what they then called global warming, i guess now they’ve given up trying to predict if its getting warmer or colder and settled on, its just changing) they don’t mention the ozone layer so much now….

To me this whole climate scientist endeavour looks like medieval priests telling peasants that couldn’t read what the bible says, and conveniently the bible says pay more tithes to your priest or suffer hell on earth.

If you think that it is quite likely that the field of climate science is biased and untrustworthy that is clearly a legitimate point of view, and the rest of your conclusions would follow. I obviously disagree with it, but I cannot claim that it is unreasonable.

I do not remember that ozone was ever touted as the major cause of climate change (except maybe briefly),more that it was a problem of increased UV radiation at ground level. See e.g. here.Anyway, I believe that ozone depletion has pretty much stopped now, with CFCs being banned, which would be why it is not discussed much any more.

An interesting long-term question is what kind of data would be required for you to change your mind. You cannot make controlled experiments, and historical real-life data on a complex system are likely to remain complex.

So for me it would have to be a physical experiment, but I don’t think that’s as impossible as it sounds. It cannot be beyond the wit of engineers when we live in a world where we hollowed out a mountain to build a trillion dollar particle cannon to discover elementary particles. To build an approximation of the earths atmosphere in a sealed environment and do temperature experiments on it, that sounds a lot more achievable than the former to me. I’d accept the results of a best efforts, as flawed as that may be, real world experiment over another glorified game of Tetris being called a climate simulation.

Unfortunately, I doubt you could ever get that. The first-order effect of changing atmospheric CO2 are well understood physics by now. Calculating the effect reliably (all other things remaining equal) for the earth with all its complex geography should be doable, if tough. What brings you down are the various knock-on effects and how they interact: atmospheric water vapour, cloud patterns, vegetation, melting of ice and snow, not to speak of methane outgassing from permafrost or changing ocean currents. A small-scale experiment would be too oversimplified to be realistic, and a realistic experiment would have to be close to planet-sized. And, unlike computer simulations, you could not redo it with lots of different starting conditions.

We could do what the Chinese are doing, which is to grow our economies until we’re so rich we can afford not to care.

Why aren’t we building mile-thick concrete canopies over every city in case an asteroid falls on one? Your logic requires that we should be doing that as well.

Not necessarily. It depends how bad the worst case would be, how likely we estimate the bad outcomes are, and what would be the cost of doing something about them. The estimates are obviously rather uncertain, but it is the same kind of calculation we all do every time we consider whether to buy insurance. I’d say that as a minimum the bad-but-plausible outcomes are bad enough that they are worth a fair bit of effort to avoid – and certainly too bad for even rich societies to just ignore. In short, you cannot dismiss this out of hand. How far we should be willing to go is admittedly less obvious to decide.

No, this is just the “precautionary principle” fallacy invented at exactly the same time as climate science. You would not buy insurance if you did not know whether the risk insured even exists and if the payout was unknown.

Predictions so far have been pretty poor.

Remember this?

Where are they?

If Rasmus believes what is objectively untrue – that there is a consensus in sync with the progressive media narrative on climate change – then there is nothing you can do that will improve his thinking. He’s an academic. His survival depends on accepting the faculty lounge consensus lest he find himself ostracized: a death sentence in academia.

I work in a company.

Rasmus is our Unherd ‘Control Group. Without him our conclusions would be valueless as they would merely be the roar inside the echo chamber.

Rasmus, I sometimes am one of your down voters, But I give you 5 stars, ***** for being a valued contributor.

Thanks,. I appreciate that.

Galeti, is that you? What have you done with Galeti?

In academia, it’s not called groupthink; it’s called ‘peer review’ 😉

Which has been correctly renamed “pal review” in some quarters. The only persons qualified to review your work are members of the same clique who all think the same thing.

It’s important to understand that “science” does not exist outside of people who practice scientific method. “Science” tells us nothing — scientists do, and if they’re crooked, so is the science.

It is important to understand that giving positions of Political authority and research to Minorities as policy, rather than merely expertise, makes for more inclusive science, and then the application of that science. See the Biden Administration for the example of how good this all is. Look at the breakthrough Humanity Sciences like CTR and 1619 as the shining example of inclucivising science for the new age. Remember ‘Intersectionality’ use in scientific grant proposals has gone up exponentially since 2019 for a good reason.

This is both very dangerous and presents a fantastic opportunity (if you are good enough to take it), both for reasons that are not obvious.

The danger is, it risks handing China a big advantage in research into areas the corporate and academic West is vacating, because those seeking money for research are focusing on areas where the language you use to land the grants is in ‘woke fashion’ and those handing out the grants look for those tickboxes. Let’s be clear, the Chinese are going to have no such compunctions, and will do us.

The reasons for the opportunity are more subtle, and are also linked to the fact that the corporate and academic West is vacating an arena. To explain, a bit of background first. In 1905, Einstein published his series of papers that ignited the nuclear age. From that standing start, in under four decades, the US had a working A-bomb. There are a number of implied lines of future developments from that story, too complicated to discuss in detail here, that people are simply ignoring, even if they have an inkling about them. The shocking thing is that Einstein was essentially a lone individual, no stellar academic background, no high tech labs, no huge teams of high quality colleagues, no access to the endless corporate and academic money-well, who produced his masterwork as a pure construction of symbols, working in his spare time.

Now the opportunity. People outside tech don’t fully understand this, but programming creates *precisely* the same opportunity, but open to a far bigger audience. In contrast with nuclear technologies, the programming ecosystem is far less costly, far less lethal, and much much more accessible. When nukes were first created in the 40s, the great fear was proliferation – every tinpot would acquire them. Turned out, it wasn’t that simple – the bar over which most countries couldn’t jump was science and engineering. Nukes require high-end precision mechanics, device physics and electronics. They require teams of physicists and rocket scientists. Very few countries had the necessary scientific heft, so the nuclear divide persisted, right to the early 2000s. That natural check on nuclear tech, and the fact that the US (rather than the nazis or the bolsheviks) got to nukes first, was pure luck, but people don’t see it that way. But these natural checks simply don’t exist with cutting code – anyone can do it, all you need is a laptop, the brains, and the will. Virtually everything you need to kick-start is available for free – training resources, compilers, dev tools, the lot. And the proof is the profile of many many companies of the internet age who started life in precisely this way.

Of course the same opportunity is available to nations and to corporations – in spades. But if the corporate and academic world vacates the space for woke reasons, it becomes far easier for tiny outfits and even individuals to cash in.

And this is the point: the next Einstein (or next small obscure team in Latvia or Luton) who creates the next algorithmic biggie, be it in natural language processing, artificial life, ai, genetic modelling, or simply invents some means to hack large numbers of computers in an automated way, is then going to be directly plugged into the core infrastructure of the entire world by default, and may have the potential to gain control of… *everything*.

I have never been an end of the Earther, but if I do, this is what I worry about, the hacking of the Grids. Bret Weinstein did an apocalypses article here on Unherd on, I think, a massive solar flare (one happened in late 1800s which would destroy the worlds grid).

I bought 6 – 5gallon buckets with air tight lids, + Oxygen remover packets sufficient, from Amazon for $80. I then bought the very cheapest rice at fifty cents a bound, and bought the cheapest beans and lentils at 55 cents a pound, and some bags of sugar for 50 cents a pound, and each bucket held 35 pounds of beans and rice, much more than I thought – and filled 4 of them, put in the Oxygen removers, sealed them (the O2 removers end up sucking the lids down, so you know it works). 140 pounds of dried foods – it cost me about $150. According to the internet, done this way, top quality buckets with sealing lids and O2 removers, this will last 30 years. About $5.5 a year for the insurance. Not that it will matter, but still – it may, but astounding how cheap it was!

All Mormons are required by their religion to keep one year of food in storage – it may be pointless and wasteful, but it sure is cheap.

“…it may be pointless and wasteful, but it sure is cheap…”

Surely the cheapness depends on the number of wives the Mormon has?

Good article, but it leaves out one important consideration, namely Bastiat’s unseen effects insight: the exercise described observes an increasing politicisation in published papers and grant applications, but this of course applies only to those publications that make it into print. No account is taken of the certain effect that many research ideas will not make it even to application stage because of the deterrant effect of these new priorities upon research that may offend the sensibilities in question.

I’d be cautious about this. The biggest jumps are in the words “Underrepresented”, “Diversity” and “Inclusion”. The others have relatively low representation (all under 3% with the exception of ‘women’), and the NSF awards aren’t just sciences, but also Education and HR, and social sciences.

“Inclusion”, in particular, has a specific meaning in clinical trials – ‘inclusion criteria’ being the requirements to take part in a study. Not surprisingly there was a jump last year as tons of papers were published around Covid.

And “underrepresented” has a specific meaning within the context of surveys and polling – the advent of internet surveys creating an explosion of poll-based research among peer groups (eg surveys of engineers) where sample representativeness is a constant element of reporting.

As new ideas flood into academe word counts would jump, then decline as the topic wanes in interest. To me the author feels like he’s trying to make a mountain out of a molehill.

I agree. Perhaps the most ludicrous buzzword of all (“intersectionality”) accounts for 0.3%, which ironically I find somewhat reassuring. If scientists buy in to the idea of intersectionality, we surely are all doomed. We do however have a much larger problem in public administration and workplace “culture” frameworks, where the nonsense of intersectionality is casually thrown around as if it were truth.

Neo-Marxism, that is where all those words come from.

If you are a scientist and you are making an argument to attract money you use as many of the weasel words as possible. You don’t choose these words because of your politics. The main thing is to get hold of the money.

The problem is if the money is awarded by trigger words which are basically anti-science is makes reasonable people suspect the money is going out unwisely.

Its far simpler than that. They hire consultants to help with the writing and ensure the right boxes are ticked. They look similar because the same consultants are involved in writing them.

There is a long and dishonourable tradition of managing to connect the hot topics of the day – rather improbably – to an application for the kind of research you were going to do anyway. As some cynic said in the late eighties: “Just because it is about AIDS does not mean we cannot use the opportunity to do good science”. It may well be that woke ideology is distorting the kind of research being done, but in the hard sciences, at least, it would take more than a word count to prove it.

Unfortunately, there is no question that woke ideology is having an impact, especially at the hiring level for tenure-track PIs, as well as in election to so-called esteemed national academies such as the US National Academy of Sciences.

Basically in the CDC and NIH and FDA, NHS the entire criteria is political correctness, and being a lackey of the Pharma/Health Industrial Complex.

It’s also important to know the contexts in which the terms are used. For example I was just looking at a report I wrote and discovered the term “under-represented” used three times, all of which were in the context of the experimental conditions used; nothing to do with race or gender etc.

But if the incidence of use of that term is rising, along with other crypto-Marxist buzzwords, the reasonable inference is that it’s rising for the same reason that the incidence of terms like equity,” “diversity,” “inclusion,” and “gender” is rising, no?

All those terms can be used without reference to “wokism”. “Gender” might be more of an issue, unless it is in the context of linguistics.

I’m not saying it’s not happening, I’m just being cautious about jumping to conclusions.

To the question in the title, the answer is ‘No’.

However science is carried out by humans living in various societies so their endeavours may be constrained by the views of those societies. But the scientific method deliberately sets out to avoid human bias.

So… can there be a different value for Woke Gravity? No. Can there be scientific support for the Blank Slate? No, although it might take some time to be widely accepted. Are people ‘equal’? Not in science, although perhaps within the law, politics, and philosophy (and not even then because there are exceptions)?

Trust the science not the scientists!

I tried to popularize this on The BBC in repeated questions/comments about Corona, but it didn’t really catch on. Let’s look at the Corona science and the third jab: BBC “medical experts” twist themselves into contortions trying to deny the science (third jab needed for most), as they tout “vaccine equity.” This is a sickening political position and they deliberately try to mislead BBC listeners–with the active assistance of The BBC–into thinking that their medical expertise carries over into politics.

These people are, in general, so dumb, that I seriously question their medical credentials. They are obviously not poker players and have no idea whatsoever how to act in situations where one has imperfect or incomplete information. Zero Covid? Yeah, sure!

Research is funny business. A few years ago somebody obtained a grant of £ 100 000 to research that dogs had emotions….. the conclusion was yes.

Sometimes you wonder whether such research is done to show that the scientific method can prove things we already know. Hence it sort of proves the scientific method works….

I am not familiar with the human sciences but from what I see in the medical sciences, it appears that the method is often more important than what is achieved ( a large majority of medical research papers add very little to the benefit of patients (or are wrong), according to Mr Horton editor of the Lancet in 2015) .

Hence, if research is your job, you propose research that is likely going to be funded over something that may be of high interest. Also, you choose a subject that will have a good chance of resulting in some sort of a positive outcome..

Science has become a business in many ways.