“Bitches ain’t shit but hoes and tricks.” This Snoop Dogg lyric is perhaps emblematic of why hip hop hasn’t always had the best image when it comes to women. Ever since the inception of the genre and its rise to prominence in pop culture, it has been lambasted by critics for demeaning and sexualising women, alongside glorifying a nihilistic, dog-eat-dog, “gangsta” lifestyle. Feminist writers have long indicted rap music for justifying domestic violence by portraying women as untrustworthy gold diggers, as well as for its female hypersexualisation in order to titillate a male audience.

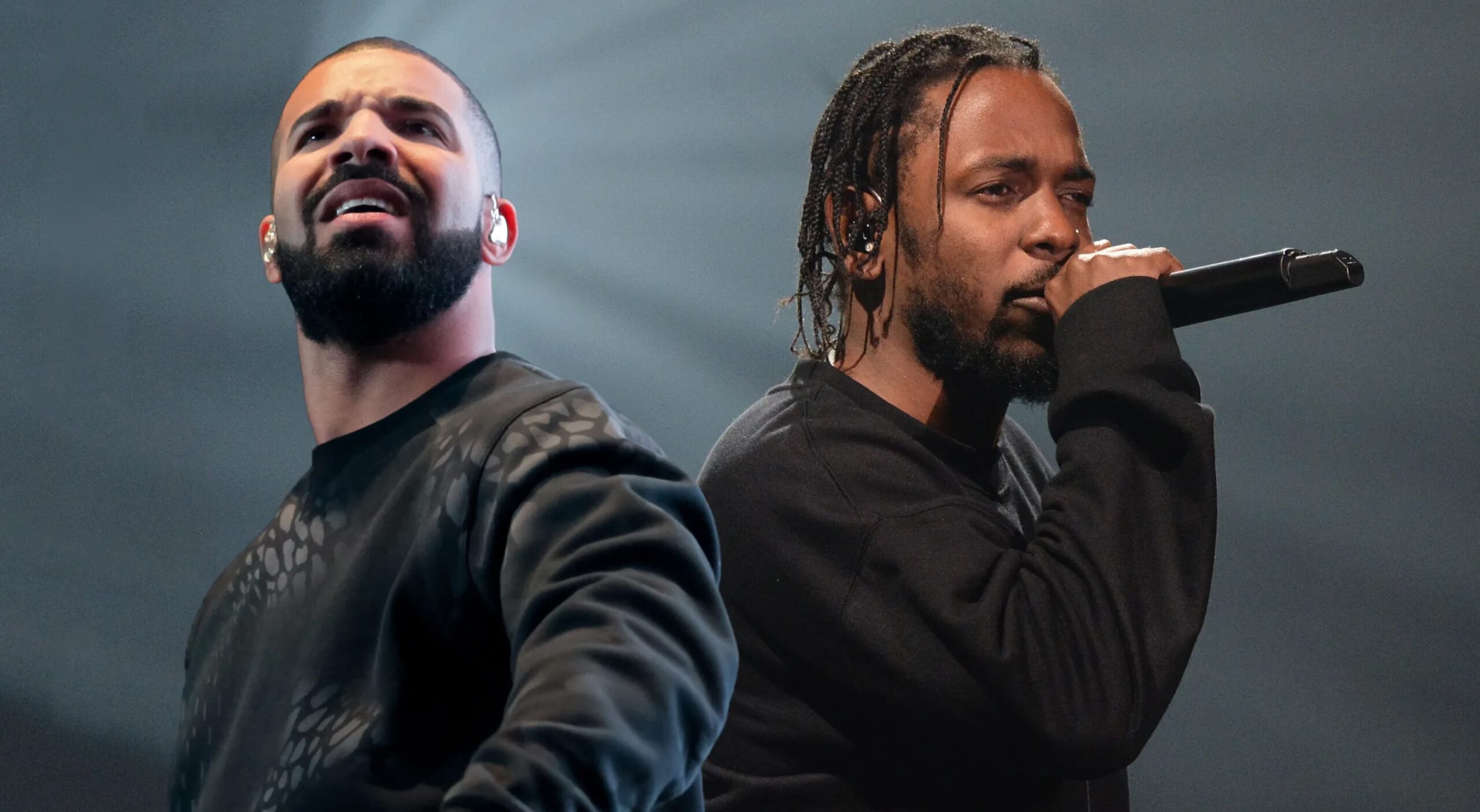

Which is why it’s intriguing that in the current instalment of the decade-long feud between rap artists Drake and Kendrick Lamar, the main point of contention isn’t the usual squabble over how many women they’ve slept with. Instead, the battle concerns who has mistreated and exploited women, leading to some particularly vicious allegations being thrown around.

Drake drew first blood in the latest round of hostilities with a three-part diss track titled “Family Matters”, calling Lamar a domestic abuser who “beat on your queen”. In “Meet the Grahams”, Lamar retaliates by attempting a psychological dissection of his rival composed through a set of letters addressed to members of Drake’s family. In a letter to Drake’s mother, Lamar calls him a “a sick man with sick habits”, comparing him to Harvey Weinstein who should “get fucked up in a cell for the rest of his life”, and says he “hates black women, hypersexualises ’em with kinks of a nympho fetish”. He goes even further in “Not Like Us”, explicitly calling Drake and his inner circle paedophiles who run a child-trafficking ring.

Could this permeation of feminist issues within a rap feud be evidence of a shift beginning within hip hop, moving away from its associations with chauvinism and machismo and towards a more progressive and socially conscious focus? The recent allegations of sexual abuse made against Diddy, one of the most influential figures within the genre today, as well as the broader consequences of #MeToo and the so-called “awokening” of 2020 have unsettled the power dynamics within show business and pop culture, of which hip hop is a crucial part.

Hip hop made its name by rebelling against the sensibilities of the “moral majority” in America. Now, it is reflecting and affirming the values of the new, progressive moral majority. Not being in tune with progressive liberalism, and being seen as a troglodytic misogynist, isn’t going to be good for an artist’s career and image. Lamar exemplifies this new breed of “socially conscious” rapper, evidenced by his statements against the Roe v Wade ruling on abortion rights at Glastonbury two years ago.

At the same time, though, it seems doubtful that one can tackle social ills such as violence against women by making unsubstantiated allegations in a song written to settle a personal feud. A more serious criticism would be that Lamar is demonstrating double standards, and that he is guilty of an instrumentalisation of these issues for a cheap “clapback”. Drake, in the same track in which he admonished Lamar for being a domestic abuser, endorsed fellow artist Chris Brown, who has a long-running and extensive history of violence against women.

Contrary to some popular opinion, hip hop is not inherently misogynistic. Yet rap music will not be a solution while misogyny remains a social ill which extends beyond any particular music genre. Hip hop, like other art forms, can only be a reflection of how society in its contradictory ways understands what was once called “the woman question”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe