Earlier this month, world leaders gathered in Egypt for the COP27 summit to discuss issues surrounding climate change. At the conference there was much talk of so-called Net Zero: the idea that we should reach a point where the amount of greenhouse gases being pumped into the atmosphere is cancelled out by the amount of greenhouse gases the atmosphere can absorb.

Numerous world leaders are targeting Net Zero by 2050, which would require enormous changes in the way we live and consume. For example, as part of these plans, leaders want to phase out vehicles that use fossil fuels, meaning none can be sold after 2038. Given how reliant we are on these vehicles for both personal transport and supply chains, this would mean huge disruptions to the way we live — and, potentially, to our standard of living.

Net Zero policies are enormously popular with the media and political elites, but this enthusiasm seems to have, thus far, shielded the idea from scrutiny. That looks set to change. A poll run by YouGov shows that 44% of the British public support “holding a national referendum to decide whether or not the UK pursues a net zero carbon policy”. Only 27% opposed. Excluding the “don’t knows”, 62% of voters support such a referendum.

Discussions of such a referendum are taking place against an unprecedented energy crisis. And while the immediate cause for the crisis is the war in Ukraine and the associated sanctions we have imposed on Russia, the reason that we are so reliant on foreign gas imports is because we have ceased using domestically sourced coal. Some of this coal has been replaced with renewables, but renewables tend to be unreliable and contingent on the weather. As a result, energy grids like Britain’s that rely heavily on them always require large amounts of natural gas as a supplement.

As the problem worsens, expect this to be more widely discussed. Already we see #netexit trending on Twitter, referring to the need for a referendum on the policy. Such a vote would be a godsend for populist politicians and commentators, who would have ample opportunity to skewer previously unchallenged experts.

Scratch the surface and it is easy to see the problems with the Net Zero narrative. Take the example of a ban on fossil fuel vehicles. Net Zero’s proponents assure us that these will be replaced with electric vehicles. Since many of us have been exposed to Teslas and their various clones, this seems intuitively plausible. But a dig into the data suggests otherwise.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeWhatever makes you think they will allow us another referendum?

Agree, the blob won’t make that mistake again

When do we want it….

Agree, the blob won’t make that mistake again

When do we want it….

Whatever makes you think they will allow us another referendum?

Mike Tyson said everyone has a plan until they are punched in the face. The cut in Russian gas is a punch in the face – the reaction is to burn coal and import LNG.

Net zero will not survive contact with reality. How much pain it will cause before it dies remains to be determined.

Kinda depends how you wanna die though doesn’t it?

I don’t think it politically feasible to switch off power. A technical solution might be politically acceptable and if the price were low enough it would be adopted by choice across the world. Some improved form of nuclear fission seems to me a plausible real world replacement, at least in part, to ‘variable wind’ plus ‘variable gas’.

I’m sorry if I misrepresent your comment, Liam, but ‘we’re going to die’ is not helpful. Problems are solved with science, engineering, planning and logic. There’s a lot of fascinating science if we dig into this topic. In addition there are economic frames: a cost-benefit analysis; a tragedy of the commons.

In any case the future costs of warming, as assessed by the IPCC, are a small fraction of the expected vastly increased global output (i.e. we will be much richer anyway) so cheer up and Merry Christmas!

You can’t die from something that’s not real.

I don’t think it politically feasible to switch off power. A technical solution might be politically acceptable and if the price were low enough it would be adopted by choice across the world. Some improved form of nuclear fission seems to me a plausible real world replacement, at least in part, to ‘variable wind’ plus ‘variable gas’.

I’m sorry if I misrepresent your comment, Liam, but ‘we’re going to die’ is not helpful. Problems are solved with science, engineering, planning and logic. There’s a lot of fascinating science if we dig into this topic. In addition there are economic frames: a cost-benefit analysis; a tragedy of the commons.

In any case the future costs of warming, as assessed by the IPCC, are a small fraction of the expected vastly increased global output (i.e. we will be much richer anyway) so cheer up and Merry Christmas!

You can’t die from something that’s not real.

Kinda depends how you wanna die though doesn’t it?

Mike Tyson said everyone has a plan until they are punched in the face. The cut in Russian gas is a punch in the face – the reaction is to burn coal and import LNG.

Net zero will not survive contact with reality. How much pain it will cause before it dies remains to be determined.

The notion that we’ll reach a point where the atmosphere cannot absorb any more CO2 is a little far-fetched given that levels have been an order of magnitude higher in the past.

Sorry – but the idea that politicians and bureaucrats can control the climate is so far beyond fatuous that a new word is required to describe just how fatuous it is. It’s equally absurd to propose that we should abandon all the means we need to adapt to the changes that are coming. We need more and cheaper energy, not less.

Like King Canute expecting the tide to go out on his command 🙂

Cnut actually made a demonstration of NOT being able to control the tides, so that his subjects would understand the limitations of kingship. Over time, that became twisted (as much else does) to suit a particular narrative.

We need a new Cnut, rather than the variations on the spelling we have controlling the agenda at the moment.

Cnut actually made a demonstration of NOT being able to control the tides, so that his subjects would understand the limitations of kingship. Over time, that became twisted (as much else does) to suit a particular narrative.

We need a new Cnut, rather than the variations on the spelling we have controlling the agenda at the moment.

You’re correct! The planet will be perfectly happy as a frozen snowball or sunken sea world or scorching desert.. it is WE who will suffer. We living creatures. If you check out all the other planets you’ll see they’re perfectly happy devoid of all life! Ours will be too. Rest assured the planet is safe.

There is no danger of the earth becoming devoid of life like the other planets. Certainly an increase in carbon dioxide is not going to bring that about. Life has flourished on the earth when there was much more carbon dioxide in the air. Plants love it.

There is no danger of the earth becoming devoid of life like the other planets. Certainly an increase in carbon dioxide is not going to bring that about. Life has flourished on the earth when there was much more carbon dioxide in the air. Plants love it.

Like King Canute expecting the tide to go out on his command 🙂

You’re correct! The planet will be perfectly happy as a frozen snowball or sunken sea world or scorching desert.. it is WE who will suffer. We living creatures. If you check out all the other planets you’ll see they’re perfectly happy devoid of all life! Ours will be too. Rest assured the planet is safe.

The notion that we’ll reach a point where the atmosphere cannot absorb any more CO2 is a little far-fetched given that levels have been an order of magnitude higher in the past.

Sorry – but the idea that politicians and bureaucrats can control the climate is so far beyond fatuous that a new word is required to describe just how fatuous it is. It’s equally absurd to propose that we should abandon all the means we need to adapt to the changes that are coming. We need more and cheaper energy, not less.

A referendum will be pointless if people still believe that wind farms are going to power the nation. For long periods this week it’s been supplying less than half a GW.

Not to mention that the concept of Net Zero is nebulous, calculated (so easily captured by activists) rather than measured, and climate zealots will never accept that we’ve reached it or that hydrocarbons must necessarily be part of the energy mix for at least the next hundred years.

If you fallow Neuralink by Musk’s terrifying mad scientists the human/brain interface is here, and soon will be working – see thee big presentation yesterday…Gates of Hell and all that…

But it will mean all that going outside cr*p will be obsolete, and so Net Zero easy – you will be linked to the entire internet in all your senses; the universe will be in your head, in your bedroom – no need to go out into it..

Yuval Noah Harar, WEF’s evil, Mad Scientist, says the world is on a cusp where the vast majority of humans will be useless for anything, and he sees drugs and computer gaming being deployed to occupy them till they do the world a favor and pass from it.

This will make Net Zero very easy.

The way to save energy is not to make it carbon free by tech – it is to make the people want to sit at home lost in a world of games, drugs, and pleasure instead of going out and doing stuff.

This is the actual plan.

If you fallow Neuralink by Musk’s terrifying mad scientists the human/brain interface is here, and soon will be working – see thee big presentation yesterday…Gates of Hell and all that…

But it will mean all that going outside cr*p will be obsolete, and so Net Zero easy – you will be linked to the entire internet in all your senses; the universe will be in your head, in your bedroom – no need to go out into it..

Yuval Noah Harar, WEF’s evil, Mad Scientist, says the world is on a cusp where the vast majority of humans will be useless for anything, and he sees drugs and computer gaming being deployed to occupy them till they do the world a favor and pass from it.

This will make Net Zero very easy.

The way to save energy is not to make it carbon free by tech – it is to make the people want to sit at home lost in a world of games, drugs, and pleasure instead of going out and doing stuff.

This is the actual plan.

A referendum will be pointless if people still believe that wind farms are going to power the nation. For long periods this week it’s been supplying less than half a GW.

Not to mention that the concept of Net Zero is nebulous, calculated (so easily captured by activists) rather than measured, and climate zealots will never accept that we’ve reached it or that hydrocarbons must necessarily be part of the energy mix for at least the next hundred years.

This is very exciting!

If Rishi Sunak was brave and clever, he would call an election on the following manifesto and win by a country mile:

1.Cap immigration to 100k net per year

2.Leave any international agreements that prevent us deporting 100% of illegal immigrants

3.Start fracking

4.Ditch the legally-binding NetZero targets

5.Make “positive discrimination” illegal (to get rid of the irritating focus on “diversity and inclusion”)

6.Make sex-changes for under 18s illegal and prohibit genetic males from going to women’s prisons, shelters and changing rooms.

Labour cannot but oppose every single one of these policies. Sunak’s Indian heritage will give him some protection from the worst of the media slandering. Biden will object and say that he is going to delay the US/UK trade deal – but he will do that anyway. And besides, these moves will play well with Republicans who could well win the presidency.

He can be a pariah in polite society or he can be an ex-PM.

Either/or!

Not exactly Liz Truss’ policy – but some echoes of it & look where that got her

Rishi is the exact opposite – stop fracking, sign up to reparations, double down on punishing people just trying to get to work by car

There’s evidence Conservative voters (at least party members) value the ideas you propose (i.e. they backed Liz) but the blob, including Conservative politicians don’t like them.

I’m suspect you are correct Andrew.

I think Truss’s mistake was to focus on economics when the problems are cultural: immigration, eco-lunatics and woke fanatics. There are economic ramifications to all of them but I would advise that politicians focus on the cultural aspects to win votes.

Liz Truss’s problem was that her proposals were not Davos Approved© so she had to go before she had chance to take her coat off.

Like Boris before her, she never sealed the deal with the Tory electorate. For instance she floated the idea of liberalising immigration (some papers suggested a free-movement deal with India!) This is obviously heretical in Tory-voting circles where a significant drop in immigration is demanded. If she had had the full-throated support of the 2019 voting cohort, she could have withstood the pressure from the Davos crowd. She didn’t and so she folded.

Boris too with his net zero claptrap. Completely at odds with his own voters. Had he gone strong on illegal and legal immigration controls, anti-woke appointments and signed off fracking and dropped the green rubbish, he would still be PM.

Sunak could – but probably won’t – learn from this.

I’d no idea so many former NF voters moved over to the Tory Party.. interesting! Or maybe they just moved to Unherd??

Good evening Liam. Hope you are well.

Good evening Liam. Hope you are well.

I’d no idea so many former NF voters moved over to the Tory Party.. interesting! Or maybe they just moved to Unherd??

Like Boris before her, she never sealed the deal with the Tory electorate. For instance she floated the idea of liberalising immigration (some papers suggested a free-movement deal with India!) This is obviously heretical in Tory-voting circles where a significant drop in immigration is demanded. If she had had the full-throated support of the 2019 voting cohort, she could have withstood the pressure from the Davos crowd. She didn’t and so she folded.

Boris too with his net zero claptrap. Completely at odds with his own voters. Had he gone strong on illegal and legal immigration controls, anti-woke appointments and signed off fracking and dropped the green rubbish, he would still be PM.

Sunak could – but probably won’t – learn from this.

To coin a phrase from BJ:

“F¤ck economics”

Good luck with that one!

I think voter Blogs is a tad smarter and a lot more concerned about his money!

Liz Truss’s problem was that her proposals were not Davos Approved© so she had to go before she had chance to take her coat off.

To coin a phrase from BJ:

“F¤ck economics”

Good luck with that one!

I think voter Blogs is a tad smarter and a lot more concerned about his money!

I’m suspect you are correct Andrew.

I think Truss’s mistake was to focus on economics when the problems are cultural: immigration, eco-lunatics and woke fanatics. There are economic ramifications to all of them but I would advise that politicians focus on the cultural aspects to win votes.

What makes you think Labour would oppose all (or any?) of them?

All Starmer would have to do is promise a referendum on ALL of them.. a far more ‘responsible’ idea ie exactly aligned with Labour’s new strategy: the “responsible’ party! Nice try though.

He would NOT win because the electorate all now know that the next tory manifesto wouldn’t be worth the paper it’s written on, just like the present one. Promise after promise broken since time immemorial (remember Cameron’s promise of net migration reduced to the tens of thousands?). Mendacity, hypocrisy and incompetence: the modus operandi of the political class.

No one’s listening or believes them any more.

Yes that would be the problem if he decided to go for it. He would need to do something first to convince the voters.

I have always thought Sunak would try to pass something through parliament- say leaving ECHR or watering down net zero – which his Wets and the opposition block and this would lead to an election. Withdraw the whip from a dozen backbenchers and go to the polls just like 2019.

Yes that would be the problem if he decided to go for it. He would need to do something first to convince the voters.

I have always thought Sunak would try to pass something through parliament- say leaving ECHR or watering down net zero – which his Wets and the opposition block and this would lead to an election. Withdraw the whip from a dozen backbenchers and go to the polls just like 2019.

But who would actually believe him?

Not exactly Liz Truss’ policy – but some echoes of it & look where that got her

Rishi is the exact opposite – stop fracking, sign up to reparations, double down on punishing people just trying to get to work by car

There’s evidence Conservative voters (at least party members) value the ideas you propose (i.e. they backed Liz) but the blob, including Conservative politicians don’t like them.

What makes you think Labour would oppose all (or any?) of them?

All Starmer would have to do is promise a referendum on ALL of them.. a far more ‘responsible’ idea ie exactly aligned with Labour’s new strategy: the “responsible’ party! Nice try though.

He would NOT win because the electorate all now know that the next tory manifesto wouldn’t be worth the paper it’s written on, just like the present one. Promise after promise broken since time immemorial (remember Cameron’s promise of net migration reduced to the tens of thousands?). Mendacity, hypocrisy and incompetence: the modus operandi of the political class.

No one’s listening or believes them any more.

But who would actually believe him?

This is very exciting!

If Rishi Sunak was brave and clever, he would call an election on the following manifesto and win by a country mile:

1.Cap immigration to 100k net per year

2.Leave any international agreements that prevent us deporting 100% of illegal immigrants

3.Start fracking

4.Ditch the legally-binding NetZero targets

5.Make “positive discrimination” illegal (to get rid of the irritating focus on “diversity and inclusion”)

6.Make sex-changes for under 18s illegal and prohibit genetic males from going to women’s prisons, shelters and changing rooms.

Labour cannot but oppose every single one of these policies. Sunak’s Indian heritage will give him some protection from the worst of the media slandering. Biden will object and say that he is going to delay the US/UK trade deal – but he will do that anyway. And besides, these moves will play well with Republicans who could well win the presidency.

He can be a pariah in polite society or he can be an ex-PM.

Either/or!

The media are (mostly) the propaganda arm of the Elite. That’s where their money is.

I expect that the Elite will consider a NetExit referendum a case of too much democracy unless they are certain to to win Net Zero Remain. So watch which media outlets are against a NetExit referendum – they are the minions.

The media are (mostly) the propaganda arm of the Elite. That’s where their money is.

I expect that the Elite will consider a NetExit referendum a case of too much democracy unless they are certain to to win Net Zero Remain. So watch which media outlets are against a NetExit referendum – they are the minions.

A referendum on the green policies was considered by Macron, in France, in order to make those policy irrevocable by future governments.

Then Macron did secret polls and renounced to run the referendum.

A referendum on the green policies was considered by Macron, in France, in order to make those policy irrevocable by future governments.

Then Macron did secret polls and renounced to run the referendum.

Glad the planet’s inability to furnish the necessary lithium, not to mention tantalum, molybdenum and other minerals, is finally getting some coverage. An excellent presentation by a senior member of the Finnish Geological Survey spells it out.

https://youtu.be/MBVmnKuBocc

There just isn’t enough unobtainium in the world.

…sure: but you assume the same requirement for cars as at present or projected at present trends. You omit to factor in such possibilities as:

1. Private cars (idle 90% of the time) being replaced with easily accessed (driverless?) rentals

2. Home working: much reduced commuting.

3. Major increase in public transport.

4. Localisation: much reduced need for long-range HGVs.

Sure, we could assume that miraculous changes will take place in our society, a la Greta Thunberg’s thundering urgings. But what if they don’t? And our leaders force us to give up our freedoms?

In other words, a colossal reduction in personal freedom and utility.

Any moron can reduce resource use by simply becoming as poor as a third world subsistence farmer. That is not what sane people consider to be an actual solution.

Plus recycling of already existing batteries, which is barely done at moment and much of the materials can be reprocessed. If we are to reach a sustainable green society, it has to actually be sustainable and green (IE. recycling and upcycling as much as possible), rather than just shifting current trends of consumerism into a more green-looking package. Consumption/energy use rates can come down, without perceived quality of life having to take a dip – we just need to re-evaluate some of the criteria by which we measure quality of life and make a lot more intelligent choices in all we do (or don’t do), purchase and use.

Plus development in already relatively developed states like the UK should be slowed down, and what we do have, consolidated and improved. There is definitely room for some new transport links, which will make use of public transport more available and attractive, but most of emphasis should be on upgraded and discrete, targeted innovations and new builds, rather swathes of new towns and so on. UK is very much near the beginning of understanding what it means to be green, and that perception is warped by those trying to drive ahead a business as normal agenda whilst controlling the narrative about how we transition to the necessity of a more sustainable society – the differences being bargained with are large tracts of land in line to be lost to sea-level rises and other natural disasters and species/biodiversity loss exacerbated by human-created climate change, plus key survival quotients like viable farming in regions that depend on subsistence agriculture, and of course affordable and green energy to live. At the moment, potentially very large numbers of people are either being condemned to starve or be displaced, which both present either moral issues for rest of us, or in case of latter, threaten to destabilise our own societies as people seek to migrate as a matter of necessity.

Plus development in already relatively developed states like the UK should be slowed down, and what we do have, consolidated and improved. There is definitely room for some new transport links, which will make use of public transport more available and attractive, but most of emphasis should be on upgraded and discrete, targeted innovations and new builds, rather swathes of new towns and so on. UK is very much near the beginning of understanding what it means to be green, and that perception is warped by those trying to drive ahead a business as normal agenda whilst controlling the narrative about how we transition to the necessity of a more sustainable society – the differences being bargained with are large tracts of land in line to be lost to sea-level rises and other natural disasters and species/biodiversity loss exacerbated by human-created climate change, plus key survival quotients like viable farming in regions that depend on subsistence agriculture, and of course affordable and green energy to live. At the moment, potentially very large numbers of people are either being condemned to starve or be displaced, which both present either moral issues for rest of us, or in case of latter, threaten to destabilise our own societies as people seek to migrate as a matter of necessity.

Sure, we could assume that miraculous changes will take place in our society, a la Greta Thunberg’s thundering urgings. But what if they don’t? And our leaders force us to give up our freedoms?

In other words, a colossal reduction in personal freedom and utility.

Any moron can reduce resource use by simply becoming as poor as a third world subsistence farmer. That is not what sane people consider to be an actual solution.

Plus recycling of already existing batteries, which is barely done at moment and much of the materials can be reprocessed. If we are to reach a sustainable green society, it has to actually be sustainable and green (IE. recycling and upcycling as much as possible), rather than just shifting current trends of consumerism into a more green-looking package. Consumption/energy use rates can come down, without perceived quality of life having to take a dip – we just need to re-evaluate some of the criteria by which we measure quality of life and make a lot more intelligent choices in all we do (or don’t do), purchase and use.

…sure: but you assume the same requirement for cars as at present or projected at present trends. You omit to factor in such possibilities as:

1. Private cars (idle 90% of the time) being replaced with easily accessed (driverless?) rentals

2. Home working: much reduced commuting.

3. Major increase in public transport.

4. Localisation: much reduced need for long-range HGVs.

Glad the planet’s inability to furnish the necessary lithium, not to mention tantalum, molybdenum and other minerals, is finally getting some coverage. An excellent presentation by a senior member of the Finnish Geological Survey spells it out.

https://youtu.be/MBVmnKuBocc

There just isn’t enough unobtainium in the world.

The problem with the Brexit referendum was that Parliament was not in favour of Brexit. I am not arguing that MPs deliberately sabotaged Brexit, but that they could not see a way of making it work and didn’t feel that they owned it. Direct democracy does not really work in our parliamentary system. Brexit needed to be a manifesto commitment by a major party to have any chance of being successfully followed through. A NetZero referendum will have the same problem

you may not be ” arguing that MPs deliberately sabotaged Brexit” but that the effective outcome.

They had a pretty good shot at it until Boris (for all his other faults) forced the act through – now they just maintain the same EU regulations and call it brexit.

Yep: all the disadvantages and none of the advantages! Great decision..

Perhaps, Andrew.(I am sure that some deliberately tried to block Brexit, despite having voted for a referendum) but that is not central to my argument. My point is that unless a governing party is committed to Brexit, it won’t happen – You will end up with Brino. Look around you. I rest my case!

Yep: all the disadvantages and none of the advantages! Great decision..

Perhaps, Andrew.(I am sure that some deliberately tried to block Brexit, despite having voted for a referendum) but that is not central to my argument. My point is that unless a governing party is committed to Brexit, it won’t happen – You will end up with Brino. Look around you. I rest my case!

It was a Conservative manifesto commitment to have a referendum on the issue in order to cancel the increasing popularity of UKIP, as instanced in their EU electoral success the previous year. It was never thought that it would succeed!.

And it never would have if:

A. The lies / distortions were contradicted.

B. The real outcomes and huge cost of Brexit were spelled out.

C. The huge advantages of remaining in the EU were listed and quantified.

Because if 1-3 above were set out accurately and truthfully only a complete fool (or filthy rich oligarch avoiding EU taxation) would have voted for Brexit.

Boy, have you got that back to front!

The wealthy supported Remain, not Brexit, because the EU was a near limitless source of cheap labour. Tony Benn saw the truth ot that back in the 70s. But not to worry Liam, you are importing your serfs from the third world now, so all is not lost!

One of the great pleasures of voting Brexit was that it offended all the right people – The money-grubbers who would sell their own grannies for a mess of potage.

Boy, have you got that back to front!

The wealthy supported Remain, not Brexit, because the EU was a near limitless source of cheap labour. Tony Benn saw the truth ot that back in the 70s. But not to worry Liam, you are importing your serfs from the third world now, so all is not lost!

One of the great pleasures of voting Brexit was that it offended all the right people – The money-grubbers who would sell their own grannies for a mess of potage.

I agree, but a commitment to a referendum is not the same as a commitment to honour the result.

And it never would have if:

A. The lies / distortions were contradicted.

B. The real outcomes and huge cost of Brexit were spelled out.

C. The huge advantages of remaining in the EU were listed and quantified.

Because if 1-3 above were set out accurately and truthfully only a complete fool (or filthy rich oligarch avoiding EU taxation) would have voted for Brexit.

I agree, but a commitment to a referendum is not the same as a commitment to honour the result.

If the flagrant lies and blatant distortions were eliminated for the proposed referendum that would also help. And if a few hard facts on likely outcomes ¹were included that might help as well!

Irrelevant to the argument.

Irrelevant to the argument.

you may not be ” arguing that MPs deliberately sabotaged Brexit” but that the effective outcome.

They had a pretty good shot at it until Boris (for all his other faults) forced the act through – now they just maintain the same EU regulations and call it brexit.

It was a Conservative manifesto commitment to have a referendum on the issue in order to cancel the increasing popularity of UKIP, as instanced in their EU electoral success the previous year. It was never thought that it would succeed!.

If the flagrant lies and blatant distortions were eliminated for the proposed referendum that would also help. And if a few hard facts on likely outcomes ¹were included that might help as well!

The problem with the Brexit referendum was that Parliament was not in favour of Brexit. I am not arguing that MPs deliberately sabotaged Brexit, but that they could not see a way of making it work and didn’t feel that they owned it. Direct democracy does not really work in our parliamentary system. Brexit needed to be a manifesto commitment by a major party to have any chance of being successfully followed through. A NetZero referendum will have the same problem

Net zero and climate catastrophism have become a religion for the ruling elite and the administrative, managerial class. They would never allow a referendum.

Traditional political parties on both the left and right are completely wed to this death cult nonsense. The bureaucracy worships at the feet of Greta Thunberg and Just Stop Oil.

You would think after 35 years of this garbage, and trillions upon trillions in investment, there would be one electric grid anywhere in the world run by wind and solar.

Net zero will be the catalyst that destroys the European economy. It will lead to the complete deindustrialization and collapse of the western block of Europe.

Portugal’s energy is already 80% from renewables.. sure we have some advantages but the main obstacles in other countries are not the absence of advantages but the absense of will, inability to change, vested interests and poor leadership etc.

Liam, check your facts before you repeat such nonsense. Perhaps you were misled by one of these “gonna do” type statements (from Wikipedia): “Portugal aims to be climate neutral by 2050 and to cover 80% of its electricity consumption with renewables by 2030″

Sure, and China and India and Indonesia aim to stop burning coal, Africa’s not even gonna try to develop their oil & gas (as the EU is commanding them to) , and we’re all gonna live on fairy dust.

This is not true of course. No one is 80% renewable – anywhere. More to the point, I said electric grid, not country. The only way a country like Denmark can even pretend to be 50% renewable is by importing power from other countries and areas when wind and solar fail.

“Portugal’s energy is already 80% from renewables…”

Claptrap. Get your facts right.

Liam, check your facts before you repeat such nonsense. Perhaps you were misled by one of these “gonna do” type statements (from Wikipedia): “Portugal aims to be climate neutral by 2050 and to cover 80% of its electricity consumption with renewables by 2030″

Sure, and China and India and Indonesia aim to stop burning coal, Africa’s not even gonna try to develop their oil & gas (as the EU is commanding them to) , and we’re all gonna live on fairy dust.

This is not true of course. No one is 80% renewable – anywhere. More to the point, I said electric grid, not country. The only way a country like Denmark can even pretend to be 50% renewable is by importing power from other countries and areas when wind and solar fail.

“Portugal’s energy is already 80% from renewables…”

Claptrap. Get your facts right.

The ironic thing is that they and their supporters do not even recognise their own religious behaviour, despite the dogmatic certainty of their outlook and near fanaticism on the issue. I was having a conversation on this subject with someone when stating people have had to choose these new religions in lieu of the traditional ones. Would have been better off talking to a brick wall.

Portugal’s energy is already 80% from renewables.. sure we have some advantages but the main obstacles in other countries are not the absence of advantages but the absense of will, inability to change, vested interests and poor leadership etc.

The ironic thing is that they and their supporters do not even recognise their own religious behaviour, despite the dogmatic certainty of their outlook and near fanaticism on the issue. I was having a conversation on this subject with someone when stating people have had to choose these new religions in lieu of the traditional ones. Would have been better off talking to a brick wall.

Net zero and climate catastrophism have become a religion for the ruling elite and the administrative, managerial class. They would never allow a referendum.

Traditional political parties on both the left and right are completely wed to this death cult nonsense. The bureaucracy worships at the feet of Greta Thunberg and Just Stop Oil.

You would think after 35 years of this garbage, and trillions upon trillions in investment, there would be one electric grid anywhere in the world run by wind and solar.

Net zero will be the catalyst that destroys the European economy. It will lead to the complete deindustrialization and collapse of the western block of Europe.

Yet another article that points out where pie in the sky environmentalist fantasy meets the hard cold road of reality. The numbers are the numbers. Net Zero is not realistically achievable without either a massive totalitarian global state (good luck with that) or a technological breakthrough on the scale of the atomic bomb or the steam engine. Most people still haven’t realized that yet, and when they do, they probably will be a lot less supportive of Net Zero. The author is doing a great service by writing about the real requirements of Net Zero. They need to be openly stated, debated, and scrutinized in the same way as any other political policy should be. As long as the politicians can convince people that implementing Net Zero is just a matter of planting trees, tax breaks for electric vehicles, subsidies for green technologies, and sticking it to those horrible oil companies, the ideology can survive. When people are asked to choose between NetZero vs. heating/cooling/reliable transportation, we all well know which one they’re going to pick. The leaders pushing Net Zero are probably well aware of it, or at least some of them are, but they’re riding the wave until it crashes for reasons of politics or profit or both, and whenever it becomes clear that Net Zero is a political liability, they’ll drop it like a hot potato. Politicians are, in the end, a predictable lot. At some point, everyone will basically realize what the smarter folks already know. Nobody is going to be stopping or limiting climate change. All we can realistically do is guess what changes are going to occur and prepare accordingly.

Yet another article that points out where pie in the sky environmentalist fantasy meets the hard cold road of reality. The numbers are the numbers. Net Zero is not realistically achievable without either a massive totalitarian global state (good luck with that) or a technological breakthrough on the scale of the atomic bomb or the steam engine. Most people still haven’t realized that yet, and when they do, they probably will be a lot less supportive of Net Zero. The author is doing a great service by writing about the real requirements of Net Zero. They need to be openly stated, debated, and scrutinized in the same way as any other political policy should be. As long as the politicians can convince people that implementing Net Zero is just a matter of planting trees, tax breaks for electric vehicles, subsidies for green technologies, and sticking it to those horrible oil companies, the ideology can survive. When people are asked to choose between NetZero vs. heating/cooling/reliable transportation, we all well know which one they’re going to pick. The leaders pushing Net Zero are probably well aware of it, or at least some of them are, but they’re riding the wave until it crashes for reasons of politics or profit or both, and whenever it becomes clear that Net Zero is a political liability, they’ll drop it like a hot potato. Politicians are, in the end, a predictable lot. At some point, everyone will basically realize what the smarter folks already know. Nobody is going to be stopping or limiting climate change. All we can realistically do is guess what changes are going to occur and prepare accordingly.

Does anyone know if any country has held a referendum in this area (Switzerland ?) ? Interested to know how much public consultation and consent there is here.

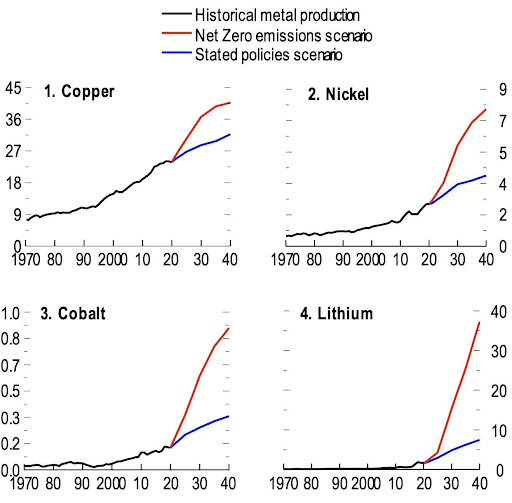

The graphs here are very pertinent. Are these generally accepted ? Is there any effort to check that climate goals are realistic when thye are defined – or is it simply assumed that a way through this will somehow be found ?

What is rarely discussed here is actually reducing energy and resource consumption – the policies are mainly about replacing existing forms of energy with ones which produce less CO2.

Agreed we should examine:

Localisation / self sufficiency in resources and energy generation.

Working from home far more. In the course of my working life I probably drove ½m miles to client firms etc. I could have done it all from home!

Replacing private cars with easily accessible rental (communal) cars. Currently private cars are idle 90% of the time! If driverless they can come to your door from their nearest location.

Someone predicted Dublin would be 8′ deep in horse shit if the growth in transportation continued.. then cars arrived! What’s needed is a lot more lateral thinking.

Yes, lateral thinking is needed. But lateral thinking is exactly what goals like net zero discourage. We need to let people find their way to a better future, not force them to use existing technology to meet an impossible goal.

You need to deal with the very large group of people who will burn maximum fossil fuels to give them a better present, and who could not care less about the future, better or otherwise. Why do you think anybody would spend their energy on a better future for everybdy, if they are not prodded?

And how will we ‘deal with’ these people, exactly? Are we talking about sending people to the gulag or a re-education camp? Are we going to start wars with nations that burn too many fossil fuels? Who do you imagine is going to be prodding people to ‘build a better future’, using what methods? Wouldn’t it be better to have a referendum, make your case, and win by democratic means so that you might justifiably implement the policies you feel are necessary? If not, what else can I conclude but that environmentalists don’t really care about the popular will and are willing to use undemocratic means to implement their preferred policies. I’m sorry, but I’m not convinced that climate change is such an existential threat that we should accept whatever deprivations to prevent it without considering the cost. If that’s what you’re selling, good luck. If the only way to stop climate change is living in a Soviet style command economy, sign me up for extinction.

And how will we ‘deal with’ these people, exactly? Are we talking about sending people to the gulag or a re-education camp? Are we going to start wars with nations that burn too many fossil fuels? Who do you imagine is going to be prodding people to ‘build a better future’, using what methods? Wouldn’t it be better to have a referendum, make your case, and win by democratic means so that you might justifiably implement the policies you feel are necessary? If not, what else can I conclude but that environmentalists don’t really care about the popular will and are willing to use undemocratic means to implement their preferred policies. I’m sorry, but I’m not convinced that climate change is such an existential threat that we should accept whatever deprivations to prevent it without considering the cost. If that’s what you’re selling, good luck. If the only way to stop climate change is living in a Soviet style command economy, sign me up for extinction.

You need to deal with the very large group of people who will burn maximum fossil fuels to give them a better present, and who could not care less about the future, better or otherwise. Why do you think anybody would spend their energy on a better future for everybdy, if they are not prodded?

Yes, lateral thinking is needed. But lateral thinking is exactly what goals like net zero discourage. We need to let people find their way to a better future, not force them to use existing technology to meet an impossible goal.

Agreed we should examine:

Localisation / self sufficiency in resources and energy generation.

Working from home far more. In the course of my working life I probably drove ½m miles to client firms etc. I could have done it all from home!

Replacing private cars with easily accessible rental (communal) cars. Currently private cars are idle 90% of the time! If driverless they can come to your door from their nearest location.

Someone predicted Dublin would be 8′ deep in horse shit if the growth in transportation continued.. then cars arrived! What’s needed is a lot more lateral thinking.

Does anyone know if any country has held a referendum in this area (Switzerland ?) ? Interested to know how much public consultation and consent there is here.

The graphs here are very pertinent. Are these generally accepted ? Is there any effort to check that climate goals are realistic when thye are defined – or is it simply assumed that a way through this will somehow be found ?

What is rarely discussed here is actually reducing energy and resource consumption – the policies are mainly about replacing existing forms of energy with ones which produce less CO2.

Enough of this tedious eco sandaloid rubbish please!!!!

Enough of this tedious eco sandaloid rubbish please!!!!

Because Brexit has been such a huge success?!?!

Because the remaining 27 EU members are facing no issues at all with their climate policies and are going to be just fine?

Grow up.

Because the remaining 27 EU members are facing no issues at all with their climate policies and are going to be just fine?

Grow up.

Because Brexit has been such a huge success?!?!

So my post got removed again, presumably because it suggested I believe climate change is real.

If you relly want to have a discussion between different viewpoints, Unherd, you really have to find a way to stop polite posts getting repeatedly bumped.

Anyone who doesn’t think climate change is real is a complete dodo! What is at issue is whether it is man made (and therefore stoppable) or unavoidable in which case the effort would be better spent on survival strategies and the likely immigration of billions of people out of drowned, scorched, otherwise uninhabitable lands into survivable countries.

It’s very difficult for me to fully buy into the human induced factor whenever I see data for longer geological periods. Take the state of CA for instance. Every time a new drought period (4-6 years) occurs, climate change is cited as the cause. This is no doubt true, just as it was true during the medieval warming period when CA experienced 2 megadroughts…one lasting about 220 years and another about 140 years. Wet periods like the 20th century have been the exception in CA for at least the last 3500 years. Natural variation seems the more likely culprit. As such, I can’t imagine the transition to renewables and electric vehicles will make any diffference at all.

So you are saying that because the climate changed before there were any humans, it is impossible that the humans can have an effect on the climate? That does not sound logical to me. To be sure people are attributing a lot of short term variation to climate change – incorrectly – just like there are people who look at a cold winter and say ‘this proves global warming is not real’. But it remains a fact that 1) humanity have pumped a lot of CO2 into the athmosphere over the last century or two. 2) The CO2 content of the athmosphere have increased significantly (that is a measurement), 3) Current scientific understanding predicts that this would result in global warming, 4) the planet is warming up, glaciers are melting etc. I’d say that is pretty decent evidence for a ‘human induced factor’.

No it’s not impossible and I also don’t think it’s illogical to claim it’s possible that natural climate cycles could mostly overwhelm anything we do in our efforts to reduce greenhouse gases. The climate extremes of the past is what lends support to this view. Those who believe humans are 100% responsible for climate change will certainly argue otherwise.

I think it’s a darn good idea to reduce anything we put into our atmosphere, soil or water that could negatively effect the environment. I’ve read all 6 of the UN IPCC main reports and the most likely temperature changes being forecasted and the CO2 reductions being called for, do not seem unmanageable to me. If the U.S. simply stuck to its natural gas path and stopped shutting down nuclear facilities, we would be well on our way to reducing emissions at a rate the IPCC insists needs to occur without installing a single additional solar panel or wind turbine or buying an additional electric vehicle. All of which will require massive amounts of energy for minerals mining and ultimately produce enormous heaps of hazardous waste. I don’t think that’s good climate policy or environmental policy regardless of a natural versus human contribution debate.

This is pretty simplistic thinking. I agree with all four of your points. It still doesn’t mean some catastrophe is awaiting us.

We know net zero will cause a humanitarian catastrophe, unless we build A LOT of nuclear power plants very quickly. We can adapt to any issues caused by climate change. Hell, the Netherlands is six feet below sea level.

No it’s not impossible and I also don’t think it’s illogical to claim it’s possible that natural climate cycles could mostly overwhelm anything we do in our efforts to reduce greenhouse gases. The climate extremes of the past is what lends support to this view. Those who believe humans are 100% responsible for climate change will certainly argue otherwise.

I think it’s a darn good idea to reduce anything we put into our atmosphere, soil or water that could negatively effect the environment. I’ve read all 6 of the UN IPCC main reports and the most likely temperature changes being forecasted and the CO2 reductions being called for, do not seem unmanageable to me. If the U.S. simply stuck to its natural gas path and stopped shutting down nuclear facilities, we would be well on our way to reducing emissions at a rate the IPCC insists needs to occur without installing a single additional solar panel or wind turbine or buying an additional electric vehicle. All of which will require massive amounts of energy for minerals mining and ultimately produce enormous heaps of hazardous waste. I don’t think that’s good climate policy or environmental policy regardless of a natural versus human contribution debate.

This is pretty simplistic thinking. I agree with all four of your points. It still doesn’t mean some catastrophe is awaiting us.

We know net zero will cause a humanitarian catastrophe, unless we build A LOT of nuclear power plants very quickly. We can adapt to any issues caused by climate change. Hell, the Netherlands is six feet below sea level.

So you are saying that because the climate changed before there were any humans, it is impossible that the humans can have an effect on the climate? That does not sound logical to me. To be sure people are attributing a lot of short term variation to climate change – incorrectly – just like there are people who look at a cold winter and say ‘this proves global warming is not real’. But it remains a fact that 1) humanity have pumped a lot of CO2 into the athmosphere over the last century or two. 2) The CO2 content of the athmosphere have increased significantly (that is a measurement), 3) Current scientific understanding predicts that this would result in global warming, 4) the planet is warming up, glaciers are melting etc. I’d say that is pretty decent evidence for a ‘human induced factor’.

“…. the likely immigration of billions of people out of drowned, scorched, otherwise uninhabitable lands into survivable countries.”

All of this was supposed to happen already. The Maldives and Pacific Islands were supposed to be under water already. Instead, 80% of them have grown in land mass. We were told there would be hundreds of millions of climate refugees by now. This was predicted 20 years ago.

After 35 years of failed predictions, you think we would be a little more skeptical than this.

It’s very difficult for me to fully buy into the human induced factor whenever I see data for longer geological periods. Take the state of CA for instance. Every time a new drought period (4-6 years) occurs, climate change is cited as the cause. This is no doubt true, just as it was true during the medieval warming period when CA experienced 2 megadroughts…one lasting about 220 years and another about 140 years. Wet periods like the 20th century have been the exception in CA for at least the last 3500 years. Natural variation seems the more likely culprit. As such, I can’t imagine the transition to renewables and electric vehicles will make any diffference at all.

“…. the likely immigration of billions of people out of drowned, scorched, otherwise uninhabitable lands into survivable countries.”

All of this was supposed to happen already. The Maldives and Pacific Islands were supposed to be under water already. Instead, 80% of them have grown in land mass. We were told there would be hundreds of millions of climate refugees by now. This was predicted 20 years ago.

After 35 years of failed predictions, you think we would be a little more skeptical than this.

Anyone who doesn’t think climate change is real is a complete dodo! What is at issue is whether it is man made (and therefore stoppable) or unavoidable in which case the effort would be better spent on survival strategies and the likely immigration of billions of people out of drowned, scorched, otherwise uninhabitable lands into survivable countries.

So my post got removed again, presumably because it suggested I believe climate change is real.

If you relly want to have a discussion between different viewpoints, Unherd, you really have to find a way to stop polite posts getting repeatedly bumped.

One hopes that in the case of this new referendum a realistic outcomes will be compared truthfully unlike the blatent lying in the Brexit Referendum (now borne out in blindingly clear real outcome). Will the possibilities of ending human civilization and species extinction be accurately set out? Or will it be another lying exercise to make fools of the voters?

Focussing on electric cars it seems clear that the day of private cars lying idle for 90% of the time will have to go and easy-access rentals and vastly improved public transport will be required. Add in the dire need for localisation resulting in the elimination of 50% of goods transportation and working from home on services and the gap might be bridged.

Will the unreliability of wind power (“political electricity” as the Danes of my acquaintance call it) be honestly spelled out ?

I doubt it, the media and political classes are technically illiterate and regurgitate Greenpeace press releases as if they were facts.

Do you support nuclear power and building more hydro dams?

90% of the blatant lies in the 2016 referendum were on the Remain side, yet sense prevailed and the right outcome happened nonetheless.

There is therefore every reason to suppose that even with the combined might of the global climate establishment pouring endless tons of bullshit into the debate, the same thing would happen if a Net Zero referendum is actually held.

However, there is almost no chance that it would ever be allowed to happen, so you can rest easy that this viciously stupid, ruthless and dishonest bandwagon will keep rollling.

Will the unreliability of wind power (“political electricity” as the Danes of my acquaintance call it) be honestly spelled out ?

I doubt it, the media and political classes are technically illiterate and regurgitate Greenpeace press releases as if they were facts.

Do you support nuclear power and building more hydro dams?

90% of the blatant lies in the 2016 referendum were on the Remain side, yet sense prevailed and the right outcome happened nonetheless.

There is therefore every reason to suppose that even with the combined might of the global climate establishment pouring endless tons of bullshit into the debate, the same thing would happen if a Net Zero referendum is actually held.

However, there is almost no chance that it would ever be allowed to happen, so you can rest easy that this viciously stupid, ruthless and dishonest bandwagon will keep rollling.

One hopes that in the case of this new referendum a realistic outcomes will be compared truthfully unlike the blatent lying in the Brexit Referendum (now borne out in blindingly clear real outcome). Will the possibilities of ending human civilization and species extinction be accurately set out? Or will it be another lying exercise to make fools of the voters?

Focussing on electric cars it seems clear that the day of private cars lying idle for 90% of the time will have to go and easy-access rentals and vastly improved public transport will be required. Add in the dire need for localisation resulting in the elimination of 50% of goods transportation and working from home on services and the gap might be bridged.

How many would say they would like a referendum on any other major issue, if asked?

Anyway, it’s a terrible idea.

Not if the accurate options were put before people.. as it’s a global issue it might be best to have a global referendum! Good luck with that!

Not if the accurate options were put before people.. as it’s a global issue it might be best to have a global referendum! Good luck with that!

How many would say they would like a referendum on any other major issue, if asked?

Anyway, it’s a terrible idea.

Don’t you think that major climate change would “require enormous changes in the way we live and consume.”? That is not something you can stop with a referendum. Changes are coming, one way or the other.

The question is: will the measures proposed by western politicians make any difference? Obviously they won’t – so we’ll just have to adapt.

There is no climate crisis. There is a campaign to destroy your standard of living and ultimately, you.

Whether you believe in the climate crisis stuff or not (and many of us are a little sceptical about some of it), there’s certainly a practical case for energy conservation and efficiency and better use and recycling of scarce resources. It does bother me that this – practical stuff we can and should do and in which we’ve already made huge progress – gets lost in the quasi-religious zeal of stuff like net zero. None of this need destroy our standard of living.

So Rasmus is correct that changes are coming, whether we like it or not. The question is whether these are practical changes or idealogical ones.

What’s weird is the fatalistic view that the coming changes will be dire. We used to think change would bring progress and greater flourishing. Things have certainly changed.

Quite. Most change creates some winners and some losers (and some unaffected). That’s just how it is. But the modern attitude seems to be that there must never be any losers and that we must protect them from any losses. Quite how this is to be paid for is never explained.

There is clearly also zero sum game thinking here – a rejection of the possibility of humans responding to the challenge of change and the assumption that they will passively suffer it and never change their behaviour. Inherent in this seems to be a belief that people’s behaviour is already perfect and beyond challenge.

Another aspect to this is the creation of “protected groups” of people who are deemed to be worthy of protection from change. You see this attitude in things like the analysis of budget measures for their impact on women – any change at all which is “negative” is protested. While no such critique is made for men (or even considered).

Quite. Most change creates some winners and some losers (and some unaffected). That’s just how it is. But the modern attitude seems to be that there must never be any losers and that we must protect them from any losses. Quite how this is to be paid for is never explained.

There is clearly also zero sum game thinking here – a rejection of the possibility of humans responding to the challenge of change and the assumption that they will passively suffer it and never change their behaviour. Inherent in this seems to be a belief that people’s behaviour is already perfect and beyond challenge.

Another aspect to this is the creation of “protected groups” of people who are deemed to be worthy of protection from change. You see this attitude in things like the analysis of budget measures for their impact on women – any change at all which is “negative” is protested. While no such critique is made for men (or even considered).

What’s weird is the fatalistic view that the coming changes will be dire. We used to think change would bring progress and greater flourishing. Things have certainly changed.

Consider the possibility borh scenarios are correct..

Whether you believe in the climate crisis stuff or not (and many of us are a little sceptical about some of it), there’s certainly a practical case for energy conservation and efficiency and better use and recycling of scarce resources. It does bother me that this – practical stuff we can and should do and in which we’ve already made huge progress – gets lost in the quasi-religious zeal of stuff like net zero. None of this need destroy our standard of living.

So Rasmus is correct that changes are coming, whether we like it or not. The question is whether these are practical changes or idealogical ones.

Consider the possibility borh scenarios are correct..

My take on this is that if climate change is inevitable, there’s very little I can do about anyway so why bother worrying. Saying that, I would rather have my house flooded by rising sea level or flattened by a tornado before implementing the kind of strict controls that climate evangelists envision for us.

As would I. There are now, as there ever were, many who would sacrifice much for freedom (see Ukraine). Whether there are enough people willing to sacrifice ‘for the planet’ or not is an open question. Knowing the history of human attempts at collectivism such as Communism in its various forms, I’m putting my money on ‘not’.

The point of current science is that is it *not* inevitable. We can make a difference to the result – if we can be bothered to try.

As would I. There are now, as there ever were, many who would sacrifice much for freedom (see Ukraine). Whether there are enough people willing to sacrifice ‘for the planet’ or not is an open question. Knowing the history of human attempts at collectivism such as Communism in its various forms, I’m putting my money on ‘not’.

The point of current science is that is it *not* inevitable. We can make a difference to the result – if we can be bothered to try.

Of course you’re absolutely correct. Hence all the down ticks. Correct re the Emperor’s clothes but not popular!!

That would depend, as ever, on how well we adapt to said changes. I humbly submit that the current climate change narrative is focusing all our technological prowess into the one area where we have very few options and a very limited ability to adapt. There simply are no good alternatives for fossil fuels right now. There probably will be one day and logically, there must be if human civilization is to survive. However, the short term prospects of replacing all this energy at reasonable cost are poor, as any objective analysis of the facts would show. I submit that we might have better results if we focus on adaptation to a changed climate through the use of the energy resources we have rather than trying to pound the sand of fossil fuel alternatives that don’t actually exist yet. If you are indeed correct and changes are coming one way or the other, the question is how to minimize the impact of climate change on human welfare rather than how to minimize climate change itself, assuming such a thing is even possible. Only environmentalist dogma and quasi-religious nature worship places any intrinsic value on ‘the planet’ as it currently exists. Science would tell you, if you cared to look past the propaganda on the surface, that the planet’s climate has changed many times, the concentration of CO2 has been much higher, and so has the average temperature, and that on none of these occasions did all life suddenly come to an end. There were changes, to be sure. Some species survived and others did not. That is the way of nature. Nature does not care whether any animal, or even humans, should go extinct. To elevate the current configuration, current temperature, current CO2 levels to the status of something sacred that must be preserved is an entirely unscientific view. It takes as an assumption that humanity is or should be regarded as a separate actor from ‘natural processes’, when there is no purely empirical rationale for such distinction. Empirically speaking, the actions of humans are as much a force of nature as a volcano or an earthquake. That the humans themselves have some conscious control over those actions is irrelevant. The only view that is purely scientific is that all species must adapt to whatever climate exists, or go extinct, and humans are no exception. Humans may use any means at their disposal to adapt, and the most efficient way of doing so may in fact be by burning more fossil fuels to create more energy to use more technology to adapt to changes rather than trying to limit the changes themselves. That is where the environmentalist logic invariably fails them. Their quasi-religion requires them to equate all species loss as a tragedy rather than a morally neutral change to the system, a system whose current configuration is just as arbitrary as any other, with the notable difference that people exist to care about it and lament its loss. Nobody mourns for the dinosaurs or the millions of other extinct species, nor should they. Environmentalist moralizing has us debating the wrong issues. Of course climate change is real. That doesn’t mean we should accept the pronouncements of climate change activists as unimpeachable truth or that we should not closely examine the basic costs and feasibility of various possible responses to climate change. It is incumbent upon us as reasoning creatures to consider the facts as objectively as possible and first discern the human costs of any action or inaction in order to preserve ourselves, our food sources, our governments, our cultures, our civil order, and yes, our standard of living. Everything beyond that is moralizing, and good luck getting all of humanity to agree on a moral code.

Excellent, excellent comment. Not sure I’ve come across this argument so forcefully articulated before.

Excellent, excellent comment. Not sure I’ve come across this argument so forcefully articulated before.

How do you know that enormous changes in the way we live and consume are coming, one way or the other? Whatever lessons we have learned in the past, all pale beside this one lesson: no one can predict the future.

Maybe not, but that is not a reason for giving up. If I am 60 with no pension or savings, I wouyld predict that I will become very poor in old age, unless I start saving ASAP. Would you just say ‘never mind, maybe I die soon or win the lottery. no one can predict the future’?

Maybe not, but that is not a reason for giving up. If I am 60 with no pension or savings, I wouyld predict that I will become very poor in old age, unless I start saving ASAP. Would you just say ‘never mind, maybe I die soon or win the lottery. no one can predict the future’?

The question is: will the measures proposed by western politicians make any difference? Obviously they won’t – so we’ll just have to adapt.

There is no climate crisis. There is a campaign to destroy your standard of living and ultimately, you.

My take on this is that if climate change is inevitable, there’s very little I can do about anyway so why bother worrying. Saying that, I would rather have my house flooded by rising sea level or flattened by a tornado before implementing the kind of strict controls that climate evangelists envision for us.

Of course you’re absolutely correct. Hence all the down ticks. Correct re the Emperor’s clothes but not popular!!

That would depend, as ever, on how well we adapt to said changes. I humbly submit that the current climate change narrative is focusing all our technological prowess into the one area where we have very few options and a very limited ability to adapt. There simply are no good alternatives for fossil fuels right now. There probably will be one day and logically, there must be if human civilization is to survive. However, the short term prospects of replacing all this energy at reasonable cost are poor, as any objective analysis of the facts would show. I submit that we might have better results if we focus on adaptation to a changed climate through the use of the energy resources we have rather than trying to pound the sand of fossil fuel alternatives that don’t actually exist yet. If you are indeed correct and changes are coming one way or the other, the question is how to minimize the impact of climate change on human welfare rather than how to minimize climate change itself, assuming such a thing is even possible. Only environmentalist dogma and quasi-religious nature worship places any intrinsic value on ‘the planet’ as it currently exists. Science would tell you, if you cared to look past the propaganda on the surface, that the planet’s climate has changed many times, the concentration of CO2 has been much higher, and so has the average temperature, and that on none of these occasions did all life suddenly come to an end. There were changes, to be sure. Some species survived and others did not. That is the way of nature. Nature does not care whether any animal, or even humans, should go extinct. To elevate the current configuration, current temperature, current CO2 levels to the status of something sacred that must be preserved is an entirely unscientific view. It takes as an assumption that humanity is or should be regarded as a separate actor from ‘natural processes’, when there is no purely empirical rationale for such distinction. Empirically speaking, the actions of humans are as much a force of nature as a volcano or an earthquake. That the humans themselves have some conscious control over those actions is irrelevant. The only view that is purely scientific is that all species must adapt to whatever climate exists, or go extinct, and humans are no exception. Humans may use any means at their disposal to adapt, and the most efficient way of doing so may in fact be by burning more fossil fuels to create more energy to use more technology to adapt to changes rather than trying to limit the changes themselves. That is where the environmentalist logic invariably fails them. Their quasi-religion requires them to equate all species loss as a tragedy rather than a morally neutral change to the system, a system whose current configuration is just as arbitrary as any other, with the notable difference that people exist to care about it and lament its loss. Nobody mourns for the dinosaurs or the millions of other extinct species, nor should they. Environmentalist moralizing has us debating the wrong issues. Of course climate change is real. That doesn’t mean we should accept the pronouncements of climate change activists as unimpeachable truth or that we should not closely examine the basic costs and feasibility of various possible responses to climate change. It is incumbent upon us as reasoning creatures to consider the facts as objectively as possible and first discern the human costs of any action or inaction in order to preserve ourselves, our food sources, our governments, our cultures, our civil order, and yes, our standard of living. Everything beyond that is moralizing, and good luck getting all of humanity to agree on a moral code.

How do you know that enormous changes in the way we live and consume are coming, one way or the other? Whatever lessons we have learned in the past, all pale beside this one lesson: no one can predict the future.

Don’t you think that major climate change would “require enormous changes in the way we live and consume.”? That is not something you can stop with a referendum. Changes are coming, one way or the other.