Matt Crossick/Matt Crossick/Empics Entertainment

If you haven’t already listened to the full UnHerd interview with economic historian Niall Ferguson, you should. Interviewed for the audio-documentary ‘Capitalism on a knife-edge’, he makes the counter argument that capitalism is not, in truth, in crisis. What really caught my attention, however, was his attack on education policy. Forasmuch as greedy bankers and big bucks lobbying make for shocking headlines, it is “the failures of public policy” that are in fact the greatest threat to capitalism.

Ferguson’s argument is simple: as the demand for low skilled labour declines, education provision is not keeping up (which means workers are struggling in insecure jobs with stagnating wages).

“Educational systems in the developed world are really doing quite badly, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom, and I think it’s important to recognise that failures to equip the population, and particularly young people, for the 21st century should not be blamed on capitalism or globalisation.”

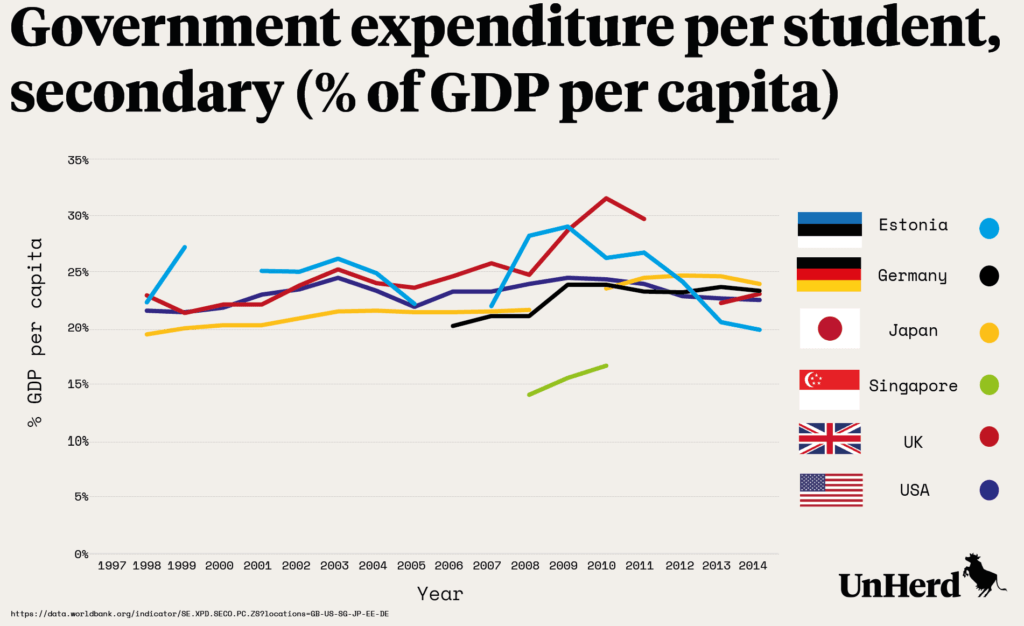

He’s right; although schooling is just one of the building blocks of a 21st century workforce – on the job training and adult skills provision are also important. As Ferguson highlights, despite relatively high expenditure (see the graph below), neither the US or UK perform particularly well in international education league tables. Using the international PISA assessment, the two nations are middling, with Singapore, Japan and Estonia at the top.[1. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a worldwide analysis of pupil performance aged 15 in science, maths and reading. The latest PISA results from 2015 show the US hovering around average for science and reading, and just below for maths. The UK performs better, but only just. TIMSS is another measure, also focused on maths and science. Against this measure the US and UK do better, but are still some way off the highest achievers like Singapore.] In a globally competitive world – and one in which demand for high skills and higher education is increasing[2. Harry Holzer, Job Market Polarization and U.S. Worker Skills: A Tale of Two Middles, Brookngs, April 2015] – the US and the UK are falling behind.

In reality, of course, there are many factors outside of school quality that determine a child’s life chances (and earning potential) – from local labour markets to family structures – but you only have to look at the wage premium for workers with college degrees to see education matters. So, what can we learn from top performing Singapore? Quite a bit. They have, for example, a much greater focus on the depth, rather than breadth, of a student’s learning; on creative thinking and developing life-long learning skills. They also look ahead to ensure the education and skills being provided will match the future economic needs of the country.[3. ‘Singapore: rapid improvement followed by strong’, OECD, 2010] Both the UK and US, while developing aspects of this in recent years, have some way to go to emulate this model.

But if failing to equip young people to participate fully in the labour market is a big public policy failure, so too is allowing so many workers to drop out of it.

Labour market participation matters for economic growth

In America, between 1960 and 2016, growth in the labour force contributed an average 1.4% to annual economic growth, which averaged 3.2% overall during the period (largely down to the huge increase in women entering the workforce). In contrast, over the coming decade, the US Congressional Budget Office predicts that growth will be “constrained” by a much slower expansion in the workforce – contributing just 0.5% annually.[4. Alan Krueger, Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate, BPEA conference draft, Brookings, 26 August 2017] It’s largely due to America’s ageing population, but it also reflects the declining participation of males, predominantly those with low qualifications.

In the past 60 years, the proportion of men in the workforce has declined by 8 percentage points, and America now has one of the lowest male participation rates in the OECD. The UK has similarly been experiencing a decline in male participation, though the trend is less marked and the rate still high. Nonetheless, with a reducing ratio of workers to retirees, reversing that trend should still be, as economist and Princeton professor Alan Krueger argues in relation to America, a “national priority”.[5. Ibid]

Where are all the workers?

To many readers, this will feel counter-intuitive – we’ve all seen the headlines on both sides of the Atlantic celebrating high employment and low unemployment. Indeed, both nations have achieved, in the economic jargon, ‘full employment’. But to get technical for a moment, what these measures don’t capture are the workers who have disappeared from the labour force entirely – remember, to be unemployed you have to be looking for work.

That brings us to another key public policy failure: across advanced economies, millions of workers are dropping out and never returning to work, and mental ill health is an increasing driver.

One, imperfect, way of quantifying this is looking at incapacity benefits .

- In the UK, there are almost 2.4 million people of working age claiming benefits for people out of work due to ill health or disability. To put that in perspective, just over 800,000 claim unemployment benefit (Jobseekers’ Allowance).

- In America, the welfare system is generally less comprehensive than in the UK, with more restrictive eligibility rules, but there are still almost nine million workers claiming social security disability benefits.

Of these claimants, in the UK half have a ‘mental or behavioural disorder’ and in the US its almost 27%. Those figures are rising and are likely to continue to do so – the proportion claiming due to mental ill health is already much higher for younger recipients.[6. In the UK, around 60% of under 35s have a mental or behavioural disorder and in the US, for under-50s, it is close to half.] Poor mental health is increasingly keeping people out of work.

In America, the most common type of mental illness is a ‘mood disorder’, for UK claimants it is depression or anxiety. With the right help, many of these people could probably work – many people with these conditions do work – but that’s the problem, the help isn’t there, or at least not on any meaningful scale. Instead of investing in mental health provision, especially at the less severe end, billions are being spent to park people on benefits. In the process, a wealth of human capital is being lost, and at the very time we can least afford it (modelling by the OECD suggests closing the disability employment gap could largely offset the negative impact of ageing).

Addressing mental ill health is a win-win

That’s a very big prize. And one government on both sides of the Atlantic should be working towards. Unlike in education, mental health services do need greater investment – parity with physical healthcare is long overdue. Timely access to support is essential, yet non-profit Mental Health America reports that 56% of Americans suffering from mental illness do not have access to treatment (although it is improving slowly) and among young people with severe depression, 80% receive no, or insufficient, support.[7. .The state of mental health in America, Mental Health America, accessed 28 September 2017] In the UK, research by the charity Mind found over half of people with a mental health problem had to wait more than three months to receive treatment, some wait more than a year, and of those who had received psychological therapy, half felt it was insufficient.[8. .We still need to talk, Mind, November 2013] More mental health specialists are needed, but so is greater awareness among general practitioners, who are likely to be the first port of call for sufferers – in Norway, for example, GPs can be trained, and funded, to deliver cognitive behavioural therapy.

Rehabilitative services should also be core to employment support – a significant portion of incapacity claimants start as unemployment benefit recipients.[9. .Employment and Support Allowance: the case for change, Reform, December 2015] For those with severe mental health problems, ‘Individual Placement and Support’ programmes, which integrate mental health treatment and employment support, have proven to be highly effective at getting people into work.[10. .‘IPS supported employment’, Wikipedia, accessed 28 September 2017] And work, as a wealth of evidence has shown, is generally good for mental health.

More controversially, while for some of those dependent on incapacity benefits work is quite clearly not possible, for many it is. As the OECD has argued, alongside much greater support, it is reasonable to expect claimants do more to get back to work.[11. .Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers, OECD, 2010] Both Switzerland and Luxembourg oblige claimants to engage in rehabilitative activities as a condition of their benefits. The UK and US have tried to encourage greater participation, but the neither have gone far enough, which helps explain why so few people ever return to work. Part of the answer is getting tougher.

Economic growth is driven by free markets and free trade, by innovation and disruption. Yet, as Niall Ferguson reminds us, it’s also driven by effective public policy. Wealth-creating businesses need workers with the right skills. And a growing economy is underpinned by a growing labour force. Failing to get to grips with the mental health crisis facing advanced Western nations, instead parking millions of people on passive benefits, is an outrageous failure of public policy. One that threatens future prosperity.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe