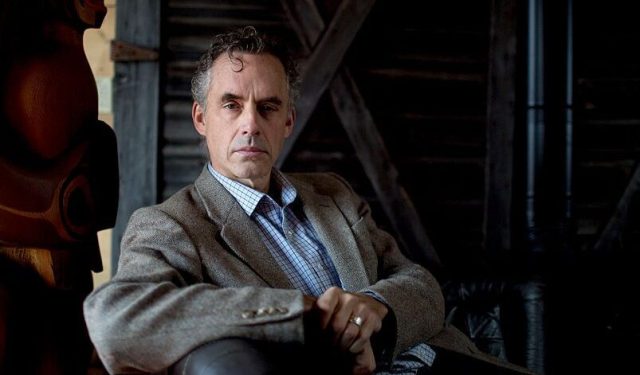

‘A manosphere-vaccine.’ Carlos Osorio/Toronto Star/Getty Images

Like every conservative intellectual, Jordan Peterson once was a man of the Left. Left-wingers were hard to come by in Seventies Alberta; Peterson grew up in what was in effect a one-party state. When he was a teenager, all but five of the representatives in the Canadian province’s Legislative Assembly were members of the Progressive Conservative Party, and of those five, four belonged to the Right-wing, crankish Social Credit Party.

The sole Left-wing voice belonged to Grant Notley, whose wife, Sandra, was the librarian at Peterson’s school, and whose daughter, Rachel, went on to be Alberta’s premier. Peterson worked for Grant and, aged only 14, came within 13 votes of being elected to the executive of his New Democratic Party. But it was Sandra who had the greatest impact on him, by introducing him to the works of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Ayn Rand, and George Orwell.

Conservative intellectuals are expected to have a narrative of their Damascene conversion, and Peterson’s came from Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. That book, he says, convinced him that socialists are, as a rule, petty and resentful people, and that the whole ideology had therefore to be rejected. No matter that Orwell had explicitly cautioned his readers against exactly this fallacy: “To recoil from socialism because so many socialists are inferior people is as absurd as refusing to travel by train because you dislike the ticket-collector’s face.” For Peterson politics is a matter of character; and he conducts his war against petty and resentful socialism by trying to inculcate good character traits in his audience.

Peterson became the world’s most influential public intellectual by supplying anxious audiences with concrete answers. 12 Rules for Life, his 2018 bestseller, addresses all the usual self-help questions: how to succeed at work, how to find love, how to establish order in a chaotic and disconcerting world. The Peterson of 2018 seemed the right kind of person to provide the answers; he looked and sounded like a man who had his affairs in order. He was adept at playing the stern father figure: “Young people are mostly worthless because they don’t know anything.” The answers themselves were straightforward, practical, and have likely helped many thousands of people. Make friends with people who want the best for you. Clean up your room. Stand up straight with your shoulders back, bucko!

Now, however, Peterson prefers to ask questions. The distance of 12 Rules for Life from his latest book, We Who Wrestle with God, reflects a shift in Peterson’s public persona. It is a shift from no-nonsense instruction to high-falutin abstraction. It is a shift typified, even, in his manner of dress: the difference between a sleek, business-like suit and a gauche, flamboyant one.

We Who Wrestle with God is a kind of homiliary, a selection of moral teachings based upon Peterson’s reading of the Bible. Chapters start and end with rhetorical questions. He recounts various Biblical stories before following them up with his favourite rhetorical question of all: “What does it mean?” Abraham apparently employs “the longest-term and most comprehensive [mating] strategies possible” — “What does all this mean?” His wife miraculously conceives when she is 90 years old — “What does this mean?”

When Peterson, on occasion, decides to answer his own questions, the reader tends to be left unsatisfied. At the beginning of Genesis, God is “moving upon the face of the waters”: what does it mean? “It means that God is mobile, obviously”, Peterson tells us, before digging deeper; “less obviously, moving is what we say when we have been struck by something deep”. Clever wordplay in English, but I don’t think it works in the Biblical Hebrew.

Peterson was accused of all manner of things when he first shot to fame: he was a “charlatan”, a “dangerous” one at that, teetering on the edges of “fascist mysticism”. But nobody back then accused him of inarticulacy. In one of his most memorable performances, with 49 million views on YouTube, he ran rings around Cathy Newman, who kept trying to pin him down with feeble gotchas (“so, what you’re saying is…”). His voice was clipped and authoritative, always adhering to one of his own 12 Rules: Be precise in your speech.

Perhaps he has now taken that precept too far. His interlocutors — Richard Dawkins, most recently — appear to find it almost impossible to sustain a conversation with him, because he’s so obsessed with defining and redefining terms, often in idiosyncratic ways (“well, that depends what X means…” has become a meme in its own right). He is, as Dawkins says, “drunk on symbols”. He indulges in those off-putting aspects of academic study that public intellectuals are supposed to eschew.

The hostility towards Peterson at the apex of his fame was always excessive. Was he not exactly what high-status liberals said they longed for? — a male role-model espousing personal responsibility, so comfortable with his emotions that he’s crying all the time. He was cast, unfairly, as a gateway drug to the manosphere. In fact, he was a manosphere-vaccine: the type of angry young man who might otherwise be attracted to the Andrew Tates of the world is precisely the type of person who most needs to be told to clean up his room and stand up straight with his shoulders back.

Yet Peterson increasingly seems to be approaching the old, uncharitable portrayal of his critics. Once he was distinguished by his calm stoicism, but now he is angry: “Up yours, woke moralists; we’ll see who cancels who!” All this naturally calls his self-help credentials into question. Should young men really be taking life advice from someone who eats only meat, salt, and water?

As Peterson the self-help guru recedes from the stage, Peterson the Biblical exegete takes his place. Yet while the self-help guru’s message worked, whatever its faults, most of the arguments of We Who Wrestle with God are dubious at best. Peterson likes to elucidate the Jungian archetypes at play in Biblical narratives by drawing analogies between them and modern pop culture. But that doesn’t work when there is a clear and discernible line of influence, as there so often is. When Superman, like Moses, exhibits the “mythological trope” of the “hero with dual ancestry”, does this really point to something deep-rooted in the human psyche? Perhaps, but it’s a poor example: Superman’s Jewish creators consciously modelled him on the Moses story.

Likewise, are all villains stand-ins for the Cain of Genesis? Sometimes it’s plausible: Scar in the Lion King, who kills his own brother, might be “as close an analogue to Cain as could be conjured in the modern imagination”. But for all Peterson’s insistences, there is nothing particularly Cain-like about Sauron or Voldemort. Nor, for that matter, are real-life supervillains: Karl Marx, says Peterson, is “Cain to the core”, because he regarded the bourgeoisie “in consequence of their success as only parasites, predators, and thieves”. We are left again with Peterson’s reading of The Road to Wigan Pier, his conception of socialism as nothing but resentment. Yet Marx, as all novices know, wrote with admiration for the bourgeoisie, which “during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together”.

Marxism — the sin of Cain — culminates, in Peterson’s telling, in the greatest evil of all: “postmodernism”. But in his distrust of “ideology”, his deconstruction of every word, his slipperiness on the question of whether Biblical stories are true (“well, that depends what you mean by ‘truth’”), there is something unmistakably postmodern about Peterson. The problem with postmodernism is that it asks questions but offers no answers. Well, I like my books to offer answers; and there might be more intellectual value in one “clean up your room, bucko” than in a thousand echoes of “what does it mean?”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe