On and on it goes. For 30 years now, Christian churches — like many institutions across the Western world — have been dealing with the consequences of their serial failures regarding abuse of children and young people: the failure to prevent or detect abuse when it was going on, the failure to deal properly with perpetrators or to report criminal acts to the authorities, and the failure to treat victims with appropriate respect and dignity. It can often feel as if there is no end in sight, even with the much-improved safeguarding procedures that are now in place.

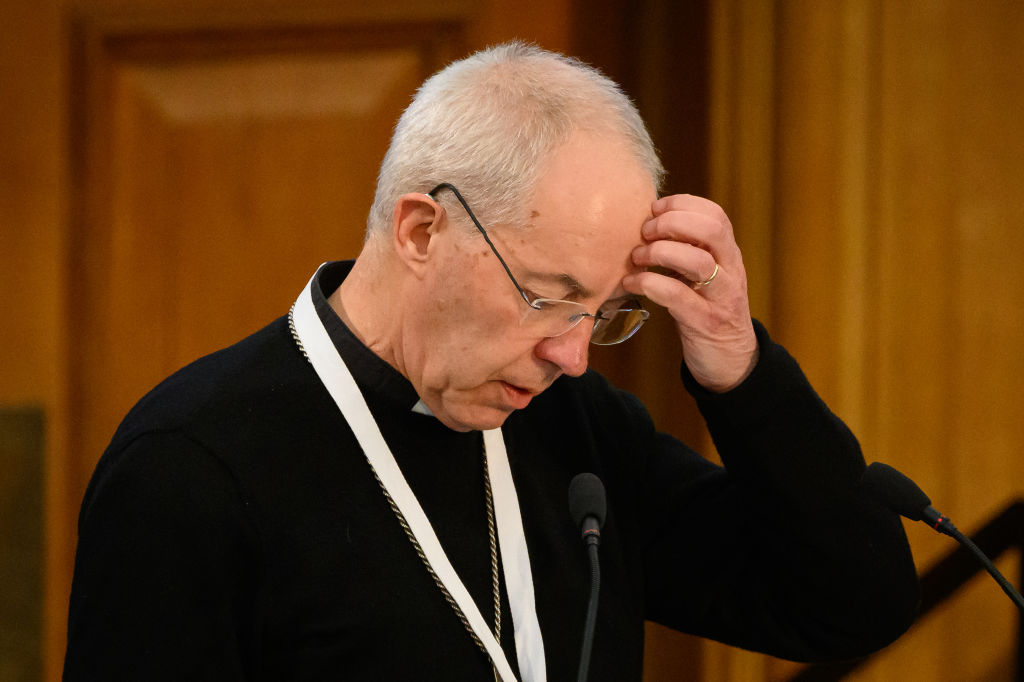

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby is one of the most senior Christian leaders to resign as a result of his role in these failures. The Makin Report into the case of the prolific abuser John Smyth was published last week, and found that Welby, who became aware of Smyth’s abuse in 2013, did not do enough to ensure that he was appropriately investigated before his death in 2018. What’s more, the Archbishop did not follow through with a commitment to meet and work with Smyth’s victims.

Welby is by many accounts a well-meaning and thoughtful man. However, in the current climate, he had little choice but to go. Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion. All Christian churches, not just the Church of England, are struggling to re-establish their credibility on the abuse issue after decades of crisis. It is simply not tenable to have as Archbishop of Canterbury a man who has not lived up to the Church’s own expectations for how leaders should respond to abuse.

Cleaning house is far from straightforward, in all fairness. When it comes to dealing with abuse allegations, Christians must balance different imperatives. The understandable desire for a zero-tolerance approach has to be balanced by a commitment to due process — false or mistaken accusations, as in the cases of the Anglican George Bell and the Catholic George Pell, are unusual but far from unknown. More challengingly, the possibility of repentance and forgiveness for offenders cannot be entirely forgotten, even if it is rightly not emphasised over care for victims and the workings of justice. Nevertheless, the clean-up needs to continue. On my own side of the Tiber, Pope Francis has shown some very dubious judgment and poor leadership in dealing with credibly accused or convicted clerical abusers, such as Marko Rupnik, and it is unacceptable.

Many will wonder where the Church of England goes from here. It may be that Welby, by stepping down, has set a precedent for radical accountability and transparency that will, in the long run, work in the Church’s favour. The expectation of clear and decisive action, and attention to important cases, has been laid down for his successors. It may also transpire that some of the anger and dismay created by the Smyth case, and Welby’s role in it, will focus on him as an individual rather than the office, allowing the next archbishop to start with a cleaner slate.

But even if this does happen, the pressing need for consistently effective and compassionate institutional action on abuse will remain — for all Christian churches.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe