Dublin City centre NurPhoto/SIPA/USA/PA Images

In 2015, Ireland’s GDP grew by a whopping 26%. Pretty impressive for a country that experienced one of the sharpest contractions of the financial crash. Except, of course, as everyone knows, it’s the economic equivalent of fake news. Economist and New York Times journalist Paul Krugman called it “Leprechaun economics”, which is flippant, but apt. The Irish economic model is, at least in part, predicated on a pot of gold.

Austerity helped, but it wasn’t the engine of post-recession growth

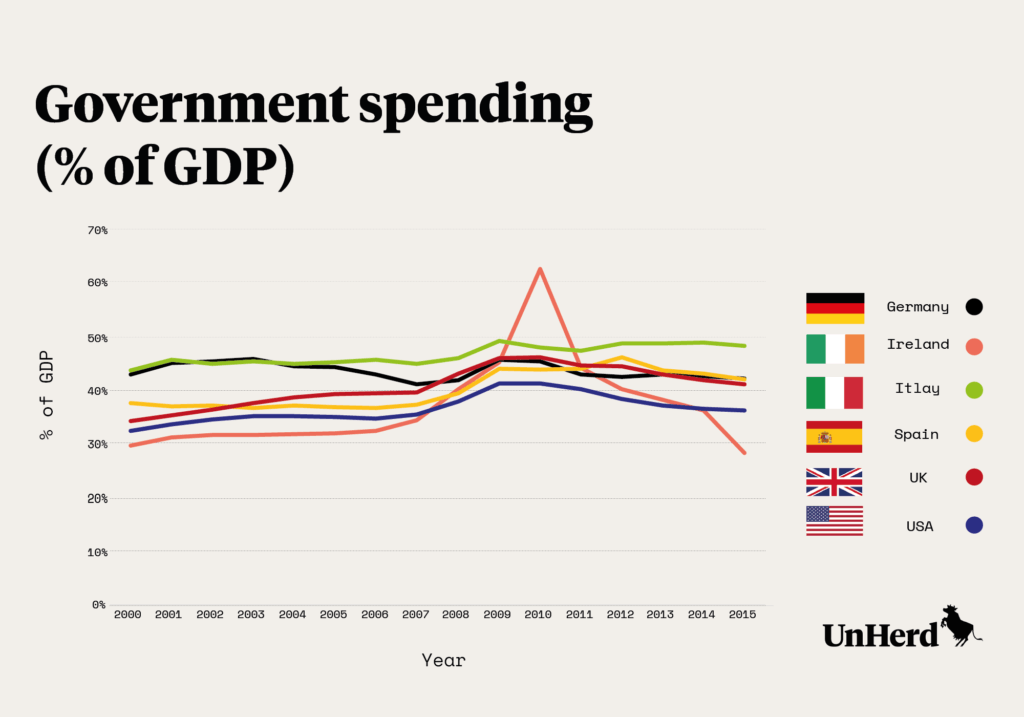

Ireland has been seen as the shining example of successful austerity. The rapid and deep fiscal consolidation implemented by the Irish government, the argument goes, led to a speedy return to health. Spending cuts (which accounted for roughly two thirds of the consolidation, revenue raising the other third) and regulatory reform allowed the economy to stabilise, and then quickly start growing. In 2016, Ireland retained its crown as the fastest growing European economy. Fiscal discipline, it seemed, equalled economic prosperity.

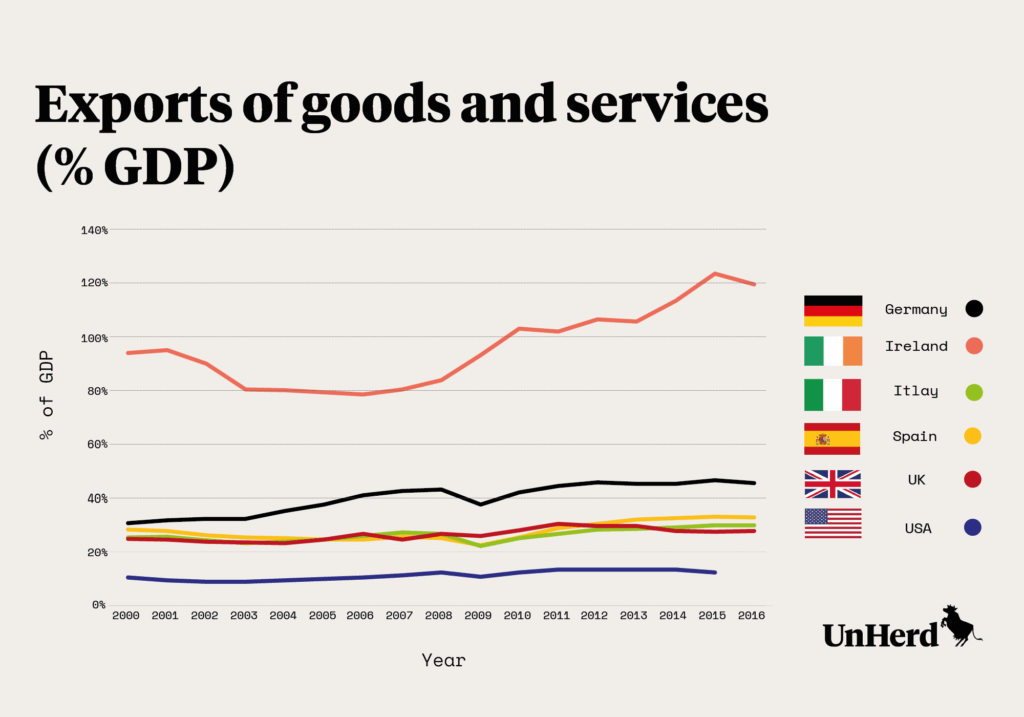

Yet, while there are good reasons for reining in spending – not least that today’s overindulgence is future generations’ debt – this interpretation of Ireland’s recovery is not quite right. Economist Stephen Kinsella argues that Ireland should be seen more as a “beautiful freak” than a “poster child” for austerity. The country’s unique conditions make universal lessons difficult, and recovery was less about cuts than exports. While domestic demand fell in the years of austerity, from 2008 exports rapidly returned to their pre-crisis levels. This Kinsella argues, was due to:

“the extremely open nature of the Irish economy, and the dominance of the export sector by multinationals…because of its extremely large ‘tradable’ sectoral composition, Ireland was able to absorb the impacts of austerity in ways that Greece, Portugal, and Spain could not”.[1. Stephen Kinsella, Not a Poster Child, but a Beautiful Freak: Economic and Fiscal Policy in Ireland, 1996-2016, 10 May 2016]

In addition, Ireland’s labour supply, which historically has demonstrated impressive elasticity, shrunk during the recession and is expanding in line with the return to growth – the year to April 2016 saw the first positive net migration figures since 2009. This is in part why unemployment has been falling consistently since 2012.

Of course, none of this means austerity didn’t matter – there is no counterfactual, you can’t create a control group and apply austerity to half the economy. Fiscal consolidation did play an important role in aligning government spending with the revenue it raises from taxes. Put another way, austerity was necessary, just not sufficient.

The same factors that saved Ireland’s economy make it fragile

Ireland may not be the poster child for austerity, but might it yet be the poster child for growth? That 26% jump in GDP was clearly smoke and mirrors. As The Irish Times reported, various “artificial” accounting practices led to a distortion in the growth figure.[2. Cliff Taylor, ‘Ireland’s GDP figures: Why 26% economic growth is a problem’, The Irish Times, 15 July 2016] Contract manufacturing,[3. Contract manufacturing is where, in this case an Irish, company outsources the manufacture of products to a foreign company, but economic ownership remains with the Irish company (even though its production may never have entered Ireland). The product is then sold abroad, at which point economic ownership changes hands and this sale is recorded as an export for the Irish company] tax inversions,[4. This is where a multinational takes over a smaller foreign entity based in a lower tax jurisdiction, thereby shifting their headquarters. The new company’s global profits are then booked to their new home] aircraft leasing and relocation of intellectual property have all contributed to grossly inflated numbers.

Yet GDP growth in 2016 was still over 5%, compared to the UK’s 1.8%, America’s 1.6% and Germany’s almost 1.9%.[5. GDP growth (annual %), The World Bank Data, accessed 8 August 2017] Setting aside 2015’s anomalies, this seems to show an economy in rude health. Except, even this far more realistic figure is misleading. Migrating corporate balance sheets is not real growth (which is why Ireland’s statistics office is looking to develop more domestically-focused measures).

It is a combination of factors that have led high-value multinationals to make Ireland their home, including a young, well-educated workforce, easy access to the EU market and the fact it is an English-speaking nation. But the very low corporate tax rate – 12.5% – is a key driver.

Research by University College Dublin’s Aidan Regan found that over 100 US tech firms have located in Ireland since 2004. “Total service exports”, he says, “now account for approximately 90 billion, and a handful of global tech-Internet firms, born out of Silicon Valley, now account for around 40 billion of this.” But while he notes that the likes of Google and Apple booking their revenues in Ireland exaggerates the country’s recovery, he also points out that high-tech expansion has delivered high-skill jobs. ICT services jobs grew from 2,900 in 2008 to almost 12,000 in 2013. It is, Regan argues, the direct result of a “state-led developmental strategy to attract inward FDI from large global firms in high-wage, high-tech service sectors”.[6. Aidan Regan, ‘Debunking myths: Why austerity and structural reforms have had little to do with Ireland’s economic recovery’, The London School of Economics and Political Science, 2 February 2016]

Ireland’s economic strategy is narrow, and that’s a high-stakes gamble

A proactive strategy to attract companies and investment is surely a good thing, something other countries might look to emulate. So far so good. But Ireland’s model is not sufficiently balanced, meaning the risks are high.

- In 2016, net inflows of foreign direct investment were 27% of Ireland’s GDP – in the UK the equivalent figure was 11.5%, in the United States 2.3% and in Germany 1.5%.[7. Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP), The World Bank data, accessed 8 August 2017]

- Although there has been a rebalancing towards income tax since the crash,[8. Stephen Kinsella, Not a Poster Child, but a Beautiful Freak: Economic and Fiscal Policy in Ireland, 1996-2016, 10 May 2016] Ireland’s corporation tax still accounted for just over 11.5% of total tax in 2015, compared to around 7% in the UK and 5% in Germany.[9. An Analysis of 2015 Corporation Tax Returns and 2016 Payments, Irish Tax and Customs, April 2017]

What happens, then, if Donald Trump delivers on his pledge to drop the corporate tax rate to 15%? Or the UK goes further than the promised cut to 17% in 2020? Although the UK Chancellor Philip Hammond has since back-tracked, he previously indicated that if economic competitiveness after Brexit required it, he would slash taxes. Last year it was reported that the UK Government had a ‘secret plan’ to halve corporation tax to 10% if post-Brexit Britain needed a boost.[10. Tim Shipman, Bojan Pancevski and Jason Allardyce, ‘Threat of UK tax cut staves off hostile EU’, The Times, 23 October 2016] Action on this in either country could see the highly mobile multinationals like the tech giants relocate, with potentially devastating consequences for Ireland.

And it’s not just the threat of a rival tax haven emerging. Ireland’s export-led recovery required buyers, and recovery in America and Britain, two of Ireland’s biggest markets, facilitated that. Economic decline in either country – or Europe more broadly – would have a significant impact on Ireland. Like the Irish banking sector before the crash, Ireland’s economy is too dependent on foreign cash. Already the uncertainty of Brexit (not to mention its implications for Ireland’s border) is a very real threat to Irish economic stability.

Future-proofing the economy would, therefore, seem sensible – even urgent. Yet, if research and development spend is a proxy for that, Ireland’s approach is dangerously cavalier. Just 1.5% of GDP in 2014 was spent on R&D, compared to 1.7% for the UK, nearly 2.9% for Germany and just over 2.7% for the US (the latter is for 2013).[11. Research and development expenditure (% of GDP), The World Bank Data, accessed 8 August 2017] There’s no sign of repairing the roof while the sun is shining.

Which brings us back to the Emerald Isle’s “Leprechaun economics”. It should enjoy its pot of foreign gold while it lasts, because its built on precarious ground. Far from being a poster child for economic recovery it risks being a further warning against excessive, narrow global dependency. If fact, other nations seeking to emulate it may be the very thing that brings Ireland’s prosperity crashing down.

*****

FURTHER READING AND LISTENING

Ireland: austerity poster child or “beautiful freak”?, Alphachat podcast, Financial Times, 16 June 2017

Cliff Taylor, ‘Ireland’s GDP figures: Why 26% economic growth is a problem’, The Irish Times, 15 July 2016

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe