Dublin City centre NurPhoto/SIPA/USA/PA Images

In 2015, Ireland’s GDP grew by a whopping 26%. Pretty impressive for a country that experienced one of the sharpest contractions of the financial crash. Except, of course, as everyone knows, it’s the economic equivalent of fake news. Economist and New York Times journalist Paul Krugman called it “Leprechaun economics”, which is flippant, but apt. The Irish economic model is, at least in part, predicated on a pot of gold.

Austerity helped, but it wasn’t the engine of post-recession growth

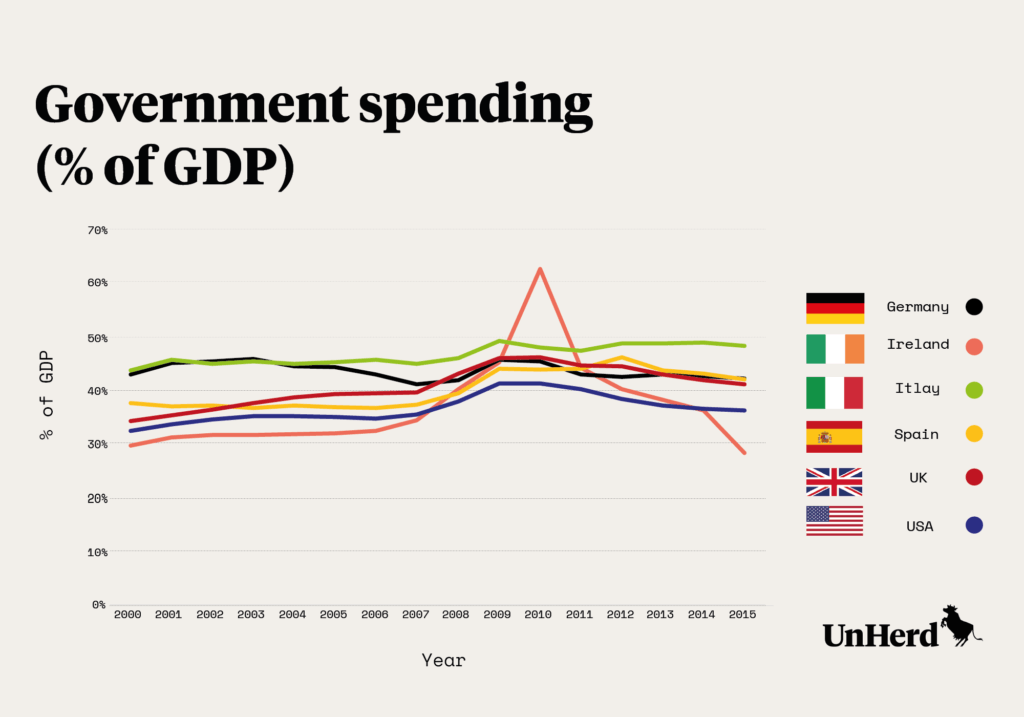

Ireland has been seen as the shining example of successful austerity. The rapid and deep fiscal consolidation implemented by the Irish government, the argument goes, led to a speedy return to health. Spending cuts (which accounted for roughly two thirds of the consolidation, revenue raising the other third) and regulatory reform allowed the economy to stabilise, and then quickly start growing. In 2016, Ireland retained its crown as the fastest growing European economy. Fiscal discipline, it seemed, equalled economic prosperity.

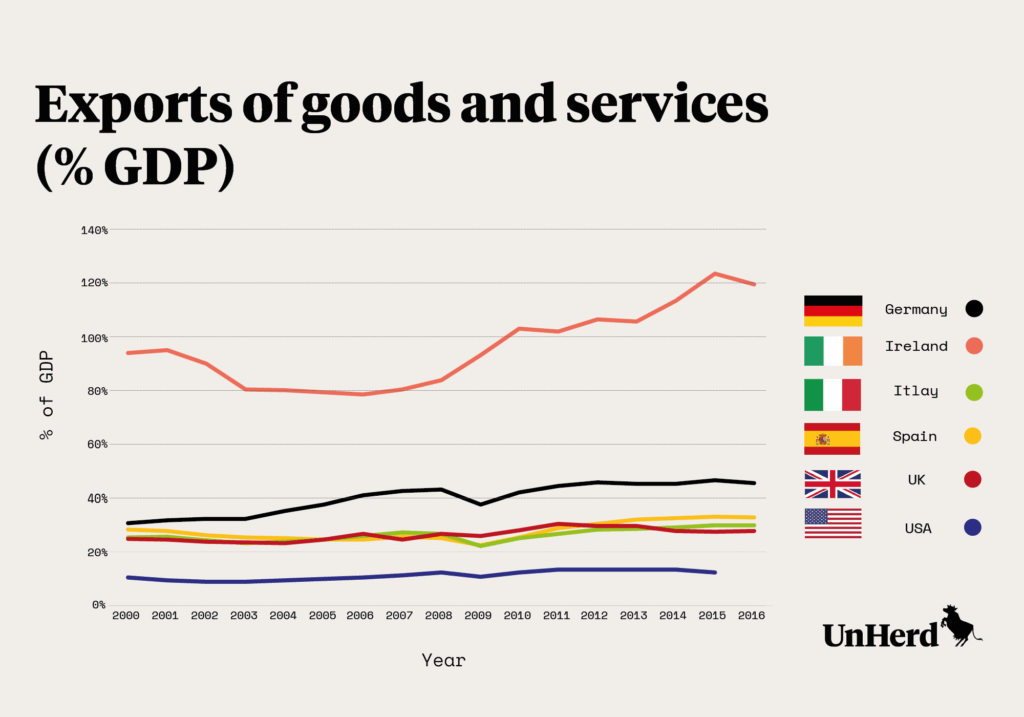

Yet, while there are good reasons for reining in spending – not least that today’s overindulgence is future generations’ debt – this interpretation of Ireland’s recovery is not quite right. Economist Stephen Kinsella argues that Ireland should be seen more as a “beautiful freak” than a “poster child” for austerity. The country’s unique conditions make universal lessons difficult, and recovery was less about cuts than exports. While domestic demand fell in the years of austerity, from 2008 exports rapidly returned to their pre-crisis levels. This Kinsella argues, was due to:

“the extremely open nature of the Irish economy, and the dominance of the export sector by multinationals…because of its extremely large ‘tradable’ sectoral composition, Ireland was able to absorb the impacts of austerity in ways that Greece, Portugal, and Spain could not”.1

In addition, Ireland’s labour supply, which historically has demonstrated impressive elasticity, shrunk during the recession and is expanding in line with the return to growth – the year to April 2016 saw the first positive net migration figures since 2009. This is in part why unemployment has been falling consistently since 2012.

Of course, none of this means austerity didn’t matter – there is no counterfactual, you can’t create a control group and apply austerity to half the economy. Fiscal consolidation did play an important role in aligning government spending with the revenue it raises from taxes. Put another way, austerity was necessary, just not sufficient.

The same factors that saved Ireland’s economy make it fragile

Ireland may not be the poster child for austerity, but might it yet be the poster child for growth? That 26% jump in GDP was clearly smoke and mirrors. As The Irish Times reported, various “artificial” accounting practices led to a distortion in the growth figure.2 Contract manufacturing,3 tax inversions,4 aircraft leasing and relocation of intellectual property have all contributed to grossly inflated numbers.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe[…] While some commentators have mistakenly argued that austerity worked in Ireland – in 2015 its GDP grew by a whopping 26 per cent – economists have corrected that Ireland should be seen more as a “beautiful freak” than a “poster child” for austerity”. […]