With the Conservative Party’s electoral fortunes plunging to ever-lower depths, Nigel Farage and even some commentators have argued that Reform UK can take over or even replace the Conservatives by the 2029 general election. Sadly for Farage, that appears very unlikely.

The opinion polls, while ghastly for the Conservatives, do not suggest the party faces an existential threat. For example, this week’s well-publicised YouGov MRP poll, which projected the Conservatives to win 140 seats, suggests they would still be the second-largest party in the House of Commons by some margin. And even if we believe the very worst opinion polls and the Conservatives are reduced to third place in the Commons behind the Liberal Democrats, they will still be comfortably the largest right-of-centre force in Parliament.

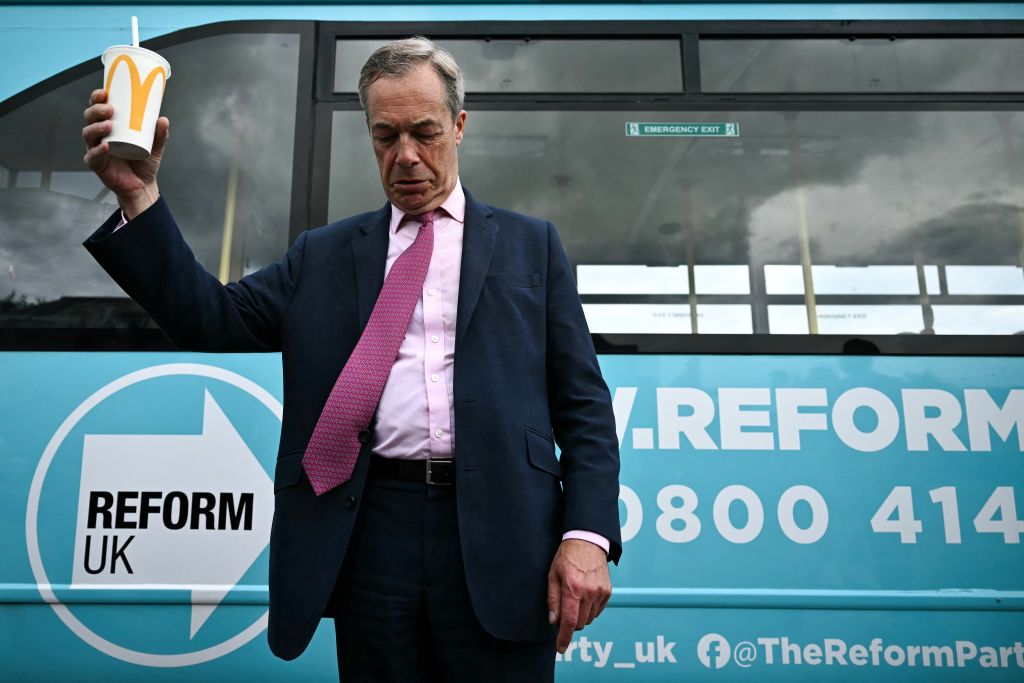

In contrast, by Farage’s own admission, even if he wins in Clacton it is very difficult to see Reform capturing more than a tiny number of seats. The problem is that the party’s vote is too evenly spread across the country. Hence, despite winning 12% of the vote at the May local elections, Reform only picked up just two council seats — and those are much easier to target than Parliamentary constituencies due to their smaller size.

Reform’s electoral predicament is hardly unusual for a new party trying to break through in the UK electoral system, and the precedent is less than encouraging. For example, part of the reason why the UK Liberal/Social Democratic Alliance performed so disappointingly at the 1983 election, winning only 23 seats despite securing 25.4% of the vote, was that such a new grouping lacked the constituency roots that Labour and the Conservatives enjoyed. Only after years of tirelessly cultivating local support did the newly merged Liberal Democrats become, for a time, a serious parliamentary force. By this time, however, the party it had hoped to replace — Labour — had recovered.

All this greatly complicates Farage’s hopes of emulating the success of the Reform Party of Canada, which merged with and effectively took over the more moderate Progressive Conservative Party, which in turn never recovered from its annihilation at the 1993 general election. At that election, the Reform Party won 52 lower house seats to the Progressive Conservatives’ two. Unless Reform UK can show at least a realistic prospect of matching the Tories in terms of seats, it is difficult to see how it could take over, let alone replace, its self-identified rival.

The only historical example of a major party being replaced involved Labour displacing the Liberals as the dominant force on the centre-left after the First World War. Labour could only do this because, through the union movement, it had access to the campaign infrastructure necessary to capitalise on Liberal weakness. Reform, however, cannot piggyback off any movement as organised as the unions.

Far from a Reform Canada-style takeover of the Conservative Party, it is more likely that Reform UK will become, at best, a small Parliamentary group. Lacking the resources and media exposure available to the official Opposition, or even to a third party, it will struggle to maintain the political momentum necessary to become a major player in UK politics.

Like so many predictions of political realignment before, this one too is likely to fizzle out.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe