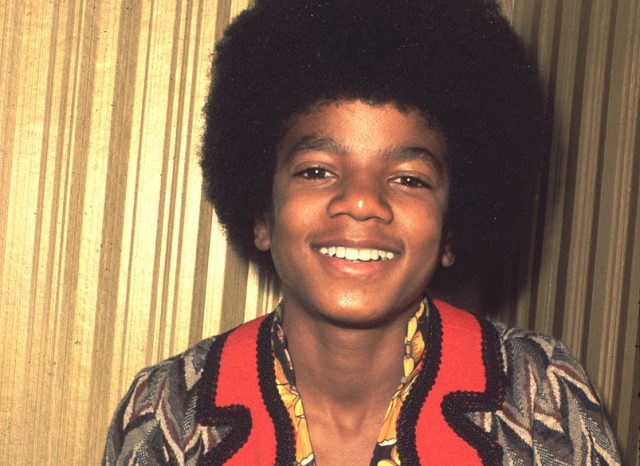

“Ben” is a rat. (Chris Walter/WireImage)

“Ben, the two of us need look no more.

We both found what we were looking for.

With a friend to call my own

I’ll never be alone

And you, my friend, will see

You’ve got a friend in me.”

When it comes to songs about friendship, Michael Jackson’s first US number one “Ben” (1972) is among the best known and the most sentimental. But unlike others of the genre — such as “Lean On Me” by Bill Withers (1972), or “With a Little Help from My Friends” by The Beatles (1967) — the key difference is that the subject isn’t human. “Ben” is a rat.

That this mawkish song about a boy and his pet rodent could have catalysed the career of one of the biggest pop stars of all time is only one aspect of the strangeness of this story. The inspiration for the song can be traced directly to a Belfast seed merchant and CND activist called Stephen Gilbert who, in 1968, published the novel Ratman’s Notebooks about a man who trains rats to wreak vengeance on his enemies. When this was filmed in 1971 as the movie Willard, the reissued paperback of the novel sold over a million copies. And it was for the sequel, Ben in 1972, that Michael Jackson provided the theme song.

All art is imitative. Even the greatest geniuses, those for whom there is seemingly no precedent, have learned their craft in the observation of other artists. The canon of literature is not formed at the behest of academics issuing decrees from their ivory towers, but rather from those works that are most emulated and admired by creatives. And this applies as much to popular culture as it does to high art. Take, for instance, T’Pau’s breakthrough hit “China in Your Hand” (1987) which was inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Some of these ripples of influence are admittedly more arbitrary than others. But there is something especially gratifying about being able to trace the work of a relatively obscure Northern Irish novelist such as Stephen Gilbert all the way to the “King of Pop”, who died 15 years ago to the day..

I remember speaking to a senior member of the Northern Irish Arts Council who was lamenting his country’s poor track record of sustaining the legacy of its creative sons and daughters. Of course, the likes of C.S. Lewis need no further promotion, but what of the lesser-known names? When I attempted to arrange a blue plaque for the birthplace of Belfast novelist Forrest Reid, I was met with bafflement from one of the decision-makers. Even this person so steeped in local culture apparently had no idea that Reid was considered Northern Ireland’s foremost novelist by E.M. Forster, and had won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction in 1944. Such is the fickle nature of literary trends.

As for Gilbert, you won’t find his work on any of the shelves of Belfast’s bookshops. But there is much to admire in the five novels that were published during his lifetime. Reading these books, one is immediately struck by the sheer imaginative range on display. The Landslide (1943) is a fantastical tale about a boy who encounters primeval creatures in his village that have been brought back into existence after a landslide exposes their long-dormant eggs. Bombardier (1944) is a vivid and compelling roman à clef about the author’s experiences as a gunner in France during the war which includes some fascinating insights into the evacuation of Dunkirk from the soldier’s perspective. Gilbert followed this with Monkeyface (1948), an eccentric story about an ape boy who is brought from a forest in South America and raised in a Belfast suburb. Then came The Burnaby Experiments (1952), in which Gilbert seems to take revenge on his mentor Forrest Reid by casting him in the role of a voyeuristic villain with supernatural powers. (The intense love-hate relationship between Reid and Gilbert is far too complex and intricate to explore here.) Ratman’s Notebooks finally appeared in 1968, an outlandish horror story to round off this bizarrely varied catalogue of work.

That Ratman’s Notebooks was destined to become famous due to a Hollywood adaptation was a source of some irritation for Gilbert. He died in 2010 having refused to watch Willard, its sequel Ben, or the 2003 remake of Willard starring Crispin Glover. He wasn’t happy with the studio’s decision to christen his unnamed narrator Willard Stiles, and to relocate the story to California. His instincts were right; this off-kilter tale is far better suited to a provincial rather than a cosmopolitan setting. Ratman’s Notebooks concerns a discontented man, dominated by a scornful mother and bullied by his boss, who resorts to acts of horrific violence. Somehow this all makes so much more sense in Belfast, a city with a troubled history and where the borderland of reality and fiction has always felt malleable.

Ratman’s Notebooks is often dismissed as a lurid and dispensable work of pulp fiction, but its influence on the horror genre has been hugely significant. The critic Kim Newman has argued its success following the release of Willard “made rampaging vermin a major horror theme of the 1970s and ’80s” and has pointed out that even Stephen King’s debut Carrie (1974) follows the same story archetype of the “turning worm” revenge fantasy.

Gilbert presents Ratman’s Notebooks in the form of a diary, and opens with the arresting line: “Mother says there are rats in the rockery.” Although it would be wrong to see the narrator as a fictionalised version of Gilbert, there are certainly parallels with the author’s life. After the death of his father in 1934, the family had been compelled to adapt to more meagre circumstances. They moved from Kensington Park in East Belfast to a relatively modest terrace house just off the Antrim Road. Having grown accustomed to an affluent way of life, they were forced to make many changes; the car was sold, along with many items of furniture. “Tea isn’t high tea anymore,” Gilbert wrote in his unpublished autobiography. “Just tea, with bread, jam and margarine. Mother watches us all to make sure nobody spreads the jam or the margarine too thickly.”

In tone and substance, this could have been a line from Ratman’s Notebooks. This theme of social decline seemingly obsessed Gilbert, and recurs continually in his novels. The narrator of Ratman’s Notebooks is forced to suffer the indignity of having to work as a subordinate in a company once owned by his deceased father, a scenario that bears some resemblance to Gilbert’s own experience. As our anti-hero’s bitterness festers, so too does his desire for revenge, not solely against those who have directly wrong him, but against society as a whole.

Gilbert was born in 1912 in Newcastle, County Down. He was one of four children, although his father William also had two other daughters from a previous marriage. William was the manager of Samuel McCausland Ltd, a Belfast-based seed merchants, the business that Stephen was later to inherit. His early life was relatively privileged; the family could afford to put him through boarding school, first in England at the Leas in Hoylake, Merseyside, and then at Loretto School in Edinburgh. His headmaster at Loretto, James Greenlees, once wrote a prescient remark about Gilbert: “I think it more than probable that he will eventually do something quite out of the ordinary, as he has an original way of looking at things.” In Ratman’s Notebooks, Gilbert was to prove Greenlees right.

In the archives at Queen’s University one can read Gilbert’s immense unpublished four-volume autobiography, in which he makes clear that Ratman’s Notebooks was his final attempt to fulfil his lifelong ambitions. “My service to Mammon”, he writes, “has kept me from serving literature”. His ultimate aim, “to leave business and become a whole-time writer”, never came to fruition. That said, he enjoyed a highly successful career in the seed industry and realised his goal “to marry and have four children – two boys and two girls”. As far I am aware, I am the only person to have read his autobiography. To open the pages, I first had to clear away layers of cobwebs and desiccated spiders.

The Gilbert archives at Queen’s University gives us a fascinating insight into his creative process. He was a meticulous researcher; there are handwritten notes about rats detailing their feeding habits, and the physical and behavioural characteristics of various species. One of Gilbert’s many idiosyncrasies was to record the precise times that he began and completed his novels. For this reason, we know that he started work on the eventual version of Ratman’s Notebooks at 6:30am on St Patrick’s Day, 1967, and finished his first draft at 7:31am on Tuesday 10 October of the same year. The first outline of the novel dates from 1938, which shows that the idea had been germinating for over a quarter of a century.

A number of manuscript drafts of Ratman’s Notebooks are still extant, some of which contain tantalising annotations regarding the various directions the novel could have taken. In one handwritten note — “Ben can read” — Gilbert has even toyed with the possibility of making the story explicitly supernatural. Another note sees his unnamed narrator make the claim that “there is nothing wrong with homosexuality except that it is entirely unfashionable”. Where such a line of thought might have taken the plotline is anyone’s guess.

It is perhaps no surprise that Gilbert’s sole foray into the horror genre turned out to be his most successful book. He was instinctively drawn to the fantastical, as evinced in works such as Monkeyface, The Burnaby Experiments and the unpublished dystopian novel The Labyrinth. “I need something out of the ordinary to work round,” he wrote in his journal on 29 October 1999, “which is what has taken me to Fantasy”. His body of work is infused with a baleful darkness relating to issues of morality and human corruption. Ratman’s Notebooks is not just a revenge story, but a study of hubris. The narrator makes himself into a kind of deity to the rats, who become engines of his most malevolent desires.

And so it is remarkable that such a bleak story should ultimately lead us to Michael Jackson’s “Ben”. The lyrics by Don Black included a middle eight which Jackson later said were his favourite in all his songs: “I used to say ‘I’ and ‘me’; now it’s ‘us’, now it’s ‘we’.” This sentiment seems so far from Gilbert’s original conception that it is curious to reflect on the connection. But it’s a reminder that an artist’s legacy does not necessarily end with the work itself, and there are myriad and unexpected ways in which it might endure.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe