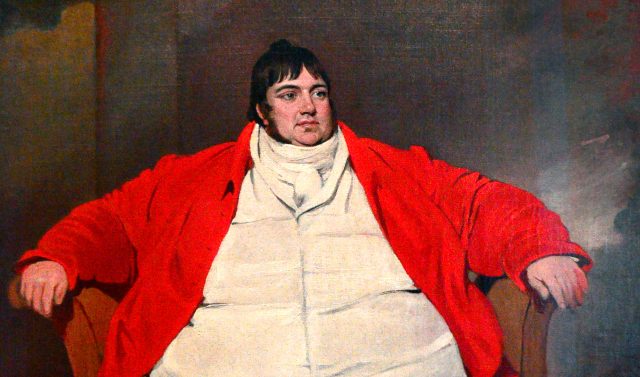

Tuck in (Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

In the 18th century, when William Hogarth wished to highlight Britain’s political and cultural superiority to pre-revolutionary France in immediately appreciable terms, he did so through the medium of food, distinguishing between the Roast Beef of Olde England, and the ruddy and rotund yeoman nation fattened on it, and the scraps of putrid flesh with which scrawny Frenchmen were forced, beside the crumbling gate of Calais, to satisfy their wants. For food and political nationhood go together like few other cultural products: witness the squabbling between Israel and Palestine over the right to commercialise hummus, Greeks and Turks over baklava, or of Russians and Ukrainians over ownership of borscht. Food is, after all, inherently political, a basic building block of national identity, and it is the humblest foodstuffs, the basic comfort foods of childhood, that are more often fought over than the elaborate confections of the great chefs.

Indeed, it would be trivially easy to trace the shifting faultlines of broader political currents through the prism of food. Witness the sudden shift within America’s food culture, as a previous generations’ celebration of the diverse culinary options provided by mass immigration has morphed into stern lectures from diaspora commentators on the vaguely-defined evils of white people appropriating “ethnic” cuisine. In Britain, equally, a slim volume could easily be written on the political import uncomfortably burdened on fish and chips or chicken tikka masala by devotees of mass migration; a cultural theorist could likewise tease apart the “Proper” label now applied to a distinct category of foodstuff — proper pies, proper burgers, proper chips — as a marker of a specific type of middle-class yearning for proletarian authenticity, while maintaining socially acceptable levels of consumption standards. Like the fetishised fry-ups of London caffs in prosperous areas targeting themselves at tracksuit-wearing millennial creatives, the Proper Burger is the self-consciously gentrified football terrace of our national cuisine, a cultural marker of a precisely measurable socioeconomic bracket.

When this dynamic is considered, Britain’s strange relationship with food, and with its own national cuisine, becomes worthy of analysis. Though much mocked by online Americans, presumably inured to the Lovecraftian horrors of their own food culture, British cuisine at its best is hearty, simple fare, showcasing the natural bounty of these islands, our waters rich with fish and seafood (much of it exported abroad to more appreciative consumers), our rain-soaked pastures the nursemaid of the free-range meat and rich dairy goods Britain has excelled in for millennia. At its best, British food displays the worth of good ingredients cooked well — and at its worst, of poor ingredients cooked badly.

Yet the much-vaunted culinary renaissance in British food from the Nineties on, despite the buoyant effect of an endless stream of glossy cookbooks on the publishing industry, does not seem to have had an appreciable effect on the food most of us eat from day to day. Which British office worker does not recognise the moment of weary, grudging submission to the lunchtime meal deal, the limp and soggy sandwich which fuels the nation’s economy? If Britain has a national dish, it is more likely to be the Ballardian misery of the provincial train station panini, simultaneously scorching hot and half-raw, than it is a steaming steak and ale pie, its crust crisp with suet, or a plate of sizzling lamb’s liver fried in butter with farmhouse bacon.

There is, as there is with every aspect of British life, a strong class dynamic to British food. The most fervent appreciators of the frugal peasant dishes of the past, the nation’s only consumers of stewed beef shin or lamb sweetbreads, are more likely to be upper-middle class, middle-aged executives, who by lunching at St John or the Quality Chop House celebrate the forgotten folkways of their own country, than the call centre workers or shop assistants who have replaced our rural and industrial proletariat. Yet who in Britain is immune to the sudden craving for comfort satiable only by a serving of rich cauliflower cheese or of dark and savoury cottage pie, or has not felt the hobbit-like “Why shouldn’t I?” satisfaction of choosing the fry up at a hotel breakfast over the continental pastry selection?

Into this rich and only partly-understood realm of symbolic meaning arrive two new books, English Food: a Social History by Diane Purkiss, and Phaidon’s glossily-produced The British Cookbook by Ben Mervis. Where Purkiss’s book, an oddly fitting successor to her excellent book on the English Civil War, is a dense and often strangely freeform collection of essays on Britain’s historic relationship with food, rich both with keen observations and dubious or baffling assertions, Mervis’s conventional cookbook is a solid if unexciting introduction to (and at times a strangely defensive apologia for) our national cuisine, aimed at what is presumed to be a sceptical international audience, interspersing stirring photographs with plainly-served prose.

Each book, in its own way, recapitulates the conventional story of Britain’s culinary history, one which reflects that of the nation as a whole, the very origin story of our unique political forms. Once, in the dim and idealised agrarian past, Britain possessed a flourishing peasant food culture, analogous to though distinct from the more celebrated peasant cuisines of our European neighbours. With land enclosure, and the eradication of a free peasant class, came industrialisation and the culinary impoverishment of the new urban proletariat, reduced to a diet of bread, potatoes and dripping. That great font of A-Level history essays, the mid-19th century political battleground of the Corn Laws, symbolises the transference of Britain’s political power from a quasi-feudal landholding class to the globalising, mercantile aspirations of their liberal supplanters, finally severing the popular connection to the land.

But this is the very same political struggle that echoes today in the battle between farming and conservation groups for revitalised domestic food production, and the firm preference of our impeccably liberal, notionally conservative ruling party for reliance on cheap imports, as if Britain still controls the global seaways. Like 19th-century liberals fulminating against the Victorian nanny state clamping down on adulterated milk and flour, our free-market thinktanks campaign today for the right of the poor to gorge themselves on bad food. When it comes to food, neither our liberals nor our conservatives have changed very much in the past 200 years, even if the political labels attached to them have almost entirely switched sides.

In the same mid-19th-century period, Ireland’s potato famine, by doing away with the poorest half of the country’s population, enabled the consolidation of a more affluent Catholic dairy-farming class, the bedrock of the modern Irish nationalism which initiated the crumbling of both the Union and the empire. And just as Drake’s introduction of the humble potato eventually redrew the map of Britain, the Empire’s steady pinkening of the world’s surface reshaped British tastes, creating a market for the spices of the subcontinent, the bland white bread flour of the Canadian prairies and the cheap frozen lamb of New Zealand. Then came the war: the food rationing celebrated as an improvement in the diets of the labouring masses also accelerated the drift towards the industrialisation of food and farming, and the extinguishing of Britain’s native farmhouse cheesemaking, orcharding and fishing traditions in pursuit of bland but secure food supplies.

The immediate post-war era saw a reaction in the form of Elizabeth David’s turning towards the bright tastes and fresh produce of the Mediterranean — the origin story of both the Nineties celebrity chef and the frozen supermarket pizza — followed by the counterreaction in the form of Jane Grigson’s classic 1974 English Food. It was the initial skirmish of the ongoing revolt of middle-class tastemakers from David’s continental affectations towards the native culinary heritage of these islands, a fraught and unfinished process analogous to the rest of our contentious relationship with Europe. There, written on a plate, lies our island story: the processes which led to Britain’s past global preeminence also eradicated the foundations of our native food culture, far more so than anywhere else in Europe. As Grigson lamented back in 1974: “we are always running after some new thing… so busy running after the latest dish, that the good things we’ve known for centuries are forgotten as quickly as the boring ones.” A perfect distillation of political conservatism, Grigson’s analysis reminds us that the history of Britain’s food is a perfectly workable metaphor for the rest of the country’s woes.

Viewed in such vein, both books are readable as not-quite-conscious expressions of the cultural moment, and there is an intriguing undertow of cultural, if not political conservatism in Purkiss’s book which contrasts with Mervis’s generic progressivism, which already seems strangely dated. An American, Mervis takes time to earnestly inform his readers in his short introductory essay that “neither the end of slavery nor the end of imperialism meant the end of white supremacy within the new British Commonwealth”, which, glancing down the list of Commonwealth countries, is presumably to be taken less as a meaningful statement than as the customary obeisance with which all American writers must perform to their new religion. Because “Britain has so few truly ‘native’ vegetables… this topic inevitably leads us back to the immigrants and invaders, who, over thousands of years” … but you get the picture, as Mervis strikes his devastating cultural blow against the red-faced root vegetable extremists.

A generation after Robin Cook, Mervis is excited to christen chicken tikka masala Britain’s national dish — perhaps more excited than anyone in Britain, bored of the bland stalwart of the budget supermarket ready meal or luridly-coloured provincial takeaway, could possibly be. As Purkiss sniffs with the frozen hauteur of the foodie, this “mongrel dish”, initially produced, so the story goes, from tinned American tomato soup to satisfy a drunk Glaswegian diner, is “barely middle class, and middle-class Britons, including those of Indian origin, tend to shake it off in favour of something more ‘authentic’”. Perhaps the cultural resonances attached to British food are as hard to appreciate from outside as is the cuisine itself? But political fashions change just as quickly as culinary ones: perhaps Mervis’s recipe for the now unfashionably-named Chicken Kiev will be updated in later editions.

A professor of 17th-century English literature at Oxford, Purkiss places British food in a finer-detailed cultural context than is available to Mervis in his brief essays, giving discursive potted histories of the Enclosure Acts, the rise and fall of the Atlantic fishing industry, the role of tinned food in the British empire, Celtic mythology and a bewildering assortment of other topics. Not all the arguments are convincing, though the book is highly entertaining: her extended diatribe on the myth of Elizabeth David, her work recast as a product of literary modernism rather than food writing, a “Lawrentian myth of escape, redemption and sensual awakening”. is captivating, concluding that “turning our faces away from England sounds profoundly unhelpful, as does encouraging whole worlds of fantasy”, for “she saved English food, but she did it by killing the Englishness of it”. Economically Left-wing — railing against the enclosure of common land and celebrating failed agrarian uprisings while noting that today’s coffee, like sugar before it, “is a cash crop grown in the developing world for consumption in richer countries” — Purkiss is comfortable introducing strongly conservative opinions. No doubt unwittingly, she echoes today’s Twitter reactionaries in observing that “the people who knocked down Euston Station and devastated the inner cities have wrecked food creation, avid as they were to have modernity and not much else”, while extolling a conservative “radical homemaker” food culture “desperate to recover a skill set and a mindset lost by their parents.”

Likewise, the post-war transferral of women from the kitchen to the workforce may have been experienced as liberation, but it was a disaster for Britain’s food culture, Purkiss observes: “one of those unfortunate moments when it turns out that feminism itself looks very like a dance to the music of business.” Perhaps the worst result, for Purkiss, is the removal of cooking from the realm of the domestic kitchen to the laboratory experiments of the male celebrity chef, the exploding seaweed gels or frozen custard mists of a Blumenthal or Adrià an expression of our estrangement from a living food culture rather than of a culinary renaissance. Unexpectedly post-liberal at times, Purkiss’s book justifies her case that “food and its decline into convenience has become the biggest and most generally agreed sign that society isn’t working and cannot continue to work in the way it currently does”.

Is there some kind of political salvation to be found in the Lancashire hotpot or toad-in-the-hole? Probably not. Yet I have often thought that, should you wish to initiate from scratch a metapolitical British nationalist project, distinct from the globalised aspirations of the Westminster class, you could do worse than take Waitrose as a model. Nationalism was always, historically, a pursuit of the affluent bourgeoisie, and even if its political content (aside from a devotion to the royal family rare among major brands) remains largely sublimated, Waitrose’s cultural production — its lovingly produced weekly newspapers and monthly magazines showcasing small-scale food producers toiling away in a timeless British countryside, its strangely feudal relationship with the Duchy of Cornwall — already echoes, in sublimated form, much of the aesthetic content and instinctive cultural meaning of classical nationalism.

The revival of Britain’s under-appreciated cuisine, halting though it may be, mocked and loved in equal measure, similarly echoes the broader angst of a nation in decline, and deep political meanings will continue to be expressed, unwittingly or not, in our conflicted relationship with our national cuisine. For Mervis, keen to emphasise Britain’s openness to the world and the bright multicultural future he sees for the nation’s food culture, change and the thrill of the new is all good and to be pursued. For Purkiss, echoing Grigson, the historical continuities of British cooking are paramount, and the sense of loss wrought by change is greater: we have lost far more than we have gained by modernity, and there is no clear path for restoration. The story of British food, full of wasted potential and opportunity, uncertain of its future direction, simultaneously seduced by new horizons and lost pastoral idylls, is the story of Britain itself.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe