Each generation has its own moral panic about emerging technologies. Silent movies were said to provoke crime; violent TV and, later, violent video games said to cause violence.

Forty years ago, we had a debate in Parliament about the harmful effects of ‘Space Invaders and other electronic games’ on children. These days it’s social media. It’s seen as addictive, tuned to hot-wire our brains’ reward functions. We talk of social media hacking our dopamine systems, as though it’s a drug. And, of course, as it does so, it is damaging us: making us depressed, lonely, anxious.

The trouble is, no one keeps their eye on the ball: as each new technology comes out, we forget the last one. But violent video games haven’t gone away. In fact, they’ve got rather better. There was a huge scare about Doom, back in the early 1990s; but if you play it now, it’s almost laughable. If its crude, blocky, pixellated graphics could inspire a generation of children to violence, what might Apex Legends be capable of? Or Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War?

The same with movies, TV, adverts: presumably, the people making them have got better at their jobs over time, and the technologies themselves have improved.

There’s a new paper out in the journal Clinical Psychological Science which points out an interesting corollary to that idea. If these technologies really do have these negative outcomes for us, and if they are, as they surely must be, improving over time, then shouldn’t the negative outcomes get worse?

To use a video games example again, because I find it easiest to understand: if it’s the realistic depiction of violence that’s the problem, then the depiction is a damn sight more realistic in Doom Eternal (2020) than it was in the original Doom (1993). Each hour of playing Eternal should have a much worse effect on us than an hour of playing the classic.

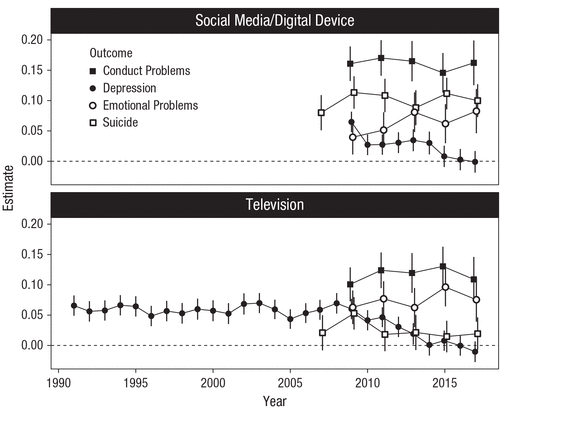

The CPS paper tried to look at that. It looked at three technologies: social media, “digital device use” (so video games or other non-work-related use of screens), and TV. Then it looked at the correlation between the use of those technologies and various mental-health outcomes in adolescents: depression, suicidality, and behavioural and emotional problems. And they looked at whether that correlation has changed over time: is an hour of playing video games in 2018 linked to worse conduct problems than an hour in 2010? Or an hour of TV in 2018 and in 1995?

Bluntly, the answer is no. There is a slight uptick in the link between digital devices/social media and emotional problems, and a decrease in the link with depression, but broadly speaking, there’s no effect:

But, if technology is having the negative effects that we all fear, then this makes no sense! These technologies ought to be getting their claws into us ever more deeply, as they become more finely tuned to capture our attention, as the blood and gore gets more realistic. But it just doesn’t seem to be happening.

This isn’t to say that no one has bad experiences with technology. Obviously some of us do. But it’s a worthy reminder that every generation has its own “video nasties” panic, and as soon as the new one comes along we forget about the last one.

It’s also worth remembering that, right now, we’re going through a process of regulating “online harms”. It is based on the idea that those harms are real. But, as Professor Andrew Przybylski of Oxford University, one of the authors of the paper, said to me: “If we’re doing these interventions, we need to make sure we get good data, otherwise mistakes will be made.” If we’re going to limit people’s rights to use the internet in the ways they want to, then it should be on the basis of good evidence. “It is really shocking and dispiriting,” says Przybylski, “that evidence isn’t at the heart of this.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe