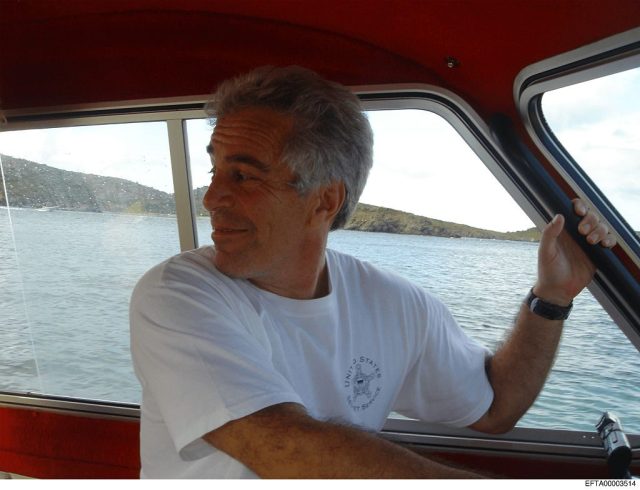

The Epstein files are the sequel to Russiagate. (The US Justice Department/Anadolu/Getty)

Two scandals have dominated the American culture wars of recent years, usually assigned to opposite teams. There was the liberal obsession with Russiagate — the idea that Donald Trump was a foreign asset and the Republic was under external attack from Russian agents and bots. Meanwhile, the Right fixated upon the Jeffrey Epstein scandal as proof that a paedophilic cabal ran the world and global elites were predatory monsters. Each side tended to treat the other’s scandal as a distraction or hoax.

The 3.5 million pages released last week by the Department of Justice confirm that these are, in fact, the same story. Treating Russiagate as a case of isolated foreign interference or the Epstein revelations as a story of individual depravity are limiting and, strange as it sounds, comforting frames because they give each side a convenient villain.

The real story is more systemic. It rests on the emergence, from the ashes of the Soviet Union, of a transnational kleptocratic class that has grown to encompass Western elites too — many of whom are only too happy to collude with the Russians, the Saudis, the Israelis, whoever, in undermining democratic institutions. The Epstein Files need to be reframed: this is a story about modern geopolitics.

It should not be surprising that Russian names are all over the Epstein Files. Russia was the laboratory that birthed the modern transnational kleptocratic class. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 created new oligarchs, as Soviet state assets were liquidated and former intelligence officers became freelance. But it also created a global template that opportunistic would-be Western oligarchs could follow in their turn.

The men who emerged from post-Soviet lawlessness — bespredel is the Russian term — built their fortunes by moving money across jurisdictions, leveraging kompromat, and treating governments as service providers instead of sovereigns. In this they were enabled by willing partners in the West, who provided the shell companies, the anonymous limited liability corporations, and the real estate loopholes. As Casey Michel has documented in American Kleptocracy, the US was not a victim of this corruption. Rather, it built the frameworks that enabled it.

Jeffrey Epstein appeared to understand this intuitively. He brokered connections across the worlds of Israeli intelligence, Gulf royals, European politicians, and the Russian state. One of his most frequent contacts was Sergey Belyakov, an FSB officer. Epstein helped Belyakov to locate tax havens and to evade sanctions; he also assisted in laundering the reputations of Russian intelligence officers, introducing them as legitimate businessmen to high-profile Americans to help them operate in the US without raising suspicion.

Russia’s former ambassador to the UN, Vitaly Churkin, was another recurring contact. He went to Epstein for advice on handling Trump. “Churkin was great,” Epstein wrote in June 2018. “He understood Trump after our conversations. It is not complex.” This was sent weeks before the Trump-Putin Helsinki summit, where Trump sided with Russia, contradicting US intelligence. Epstein also pushed to meet Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov, telling his frequent intermediary, former Norwegian prime minister Thorbjørn Jagland: “I think you might suggest to Putin that Lavrov can get insight on talking to me.”

Epstein also promoted de-dollarisation schemes like BRIC currencies and crypto, via his ties with US commerce secretary Howard Lutnick. There were the inevitable honey-traps, too — he introduced Russian women to targets like Prince Andrew and Bill Gates.

There’s even a Silicon Valley dimension. One of his associates was Masha Drokova, a former commissar of the pro-Putin youth movement Nashi who later reinvented herself as a Bay Area venture capitalist. The files show she represented Epstein as a client and embedded Russian capital in the American tech sector through the same networks. An email from 2015 finds Epstein pitching Peter Thiel, chairman of the Palantir, in order to set up a meeting in Palo Alto with his “very good friend” Belyakov, who was organising an “innovation conference in Moscow”. Epstein had previously facilitated meetings between Thiel and Churkin. The connection between Palantir’s surveillance capabilities and Moscow’s interests was framed as just another networking opportunity among friends.

The British dimension is equally revealing. Lord Mandelson, the “Prince of Darkness” who was a key architect of New Labour, appears throughout the files as a willing conduit between Whitehall and Epstein’s network. While serving as Business Secretary during the 2008 financial crisis, Mandelson forwarded internal government communications to Epstein — including advance notice of the €500 billion bailout and discussions about selling off UK government assets.

This behaviour tracks with Mandelson’s broader cultivation of Russian kleptocracy. He vacationed on the yacht of aluminium tycoon Oleg Deripaska, whose company benefited from tariff cuts that Mandelson oversaw while serving as EU Trade Commissioner. Mandelson’s firm later leveraged these ties to lobby the Kremlin directly, with Mandelson even writing to Putin to intervene in a dispute involving a Russian defence conglomerate on whose board he sat. Mandelson also offered to secure a Russian visa for Epstein using his backchannel to Deripaska. In November 2010 — when Epstein was already a convicted paedophile — he emailed Mandelson asking for a workaround to get a last-minute Russian visa. Mandelson replied the next day, confirming that he had an associate “helping on visas” to expedite the paperwork.

As we’ve known for a while, a lot of the Russiagate revelations turned out to be completely true — despite being labelled cringe lib paranoia. Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort really was colluding with the Russian agent Konstantin Kilimnik. I’ve had an interest in this subject for some time, arguing in 2017 that the collusion was a byproduct of long-standing financial schemes. The protagonist was not Putin but the money itself.

At a certain point it began to feel like shouting into the void. People were so fixated on the overhyped effects of Russian troll farms that they forgot that the source of the problem, as usual, is not anonymous shitposters but the people in charge. As David Klion argued years ago, the Steele dossier spy-thriller framing of Russiagate was a distraction; the Left should have treated the scandal as a means to critique global capitalism — rather than a pretext to leap to the defence of the FBI. We can have a debate over how much Russia influenced the 2016 election, but this is a bit of a red herring; in any case, the shady links were there years before Trump developed political aspirations.

I suspect one of the reasons Epstein was able to coast for so long is that many sensible people — especially educated liberals — found the idea of viewing the world through a conspiratorial lens vaguely distasteful and rube-coded. The liberal epistemic style has a strong allergy to connecting the dots, partly as a reasonable response to growing paranoid thinking on the Right — but also as a class marker. Baroque patterns of elite coordination became associated with Glenn Beck’s chalkboard. As Thiel wrote to Curtis Yarvin in 2014, “one of our hidden advantages is that these people” — he meant the progressive Left — “wouldn’t believe a conspiracy if it hit them over the head…Linkages make them sound crazy, and they kinda know it.”

Epstein’s case seems almost designed to exploit this blind spot. The actual facts sound like QAnon fever dreams, which made the serious people instinctively sceptical, because believing it pattern-matched to believing nonsense. The deeper issue is that educated liberals tend to have high trust in institutions and credentialed expertise. The idea that prosecutors, academics, and journalists might all fail simultaneously due to social pressure, career incentives, or wilful blindness cuts against the assumption that these systems basically work.

But if liberals were guilty of an anti-conspiratorial reflex, the Right bears responsibility too, for flooding the discourse with QAnon fever dreams, anti-vaccine hysteria, and stolen election fantasies. When everything is portrayed as a conspiracy, the term loses its sting. The tools that might have exposed Epstein’s network earlier — investigative journalism, institutional accountability, the rule of law — are precisely the liberal inheritance that the post-liberal Right treats with such contempt.

Connect the dots and the files do highlight connections that span decades and resurface in unexpected places. In a 2019 email Epstein flagged a “coincidence”: the Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev bought Trump’s Palm Beach mansion for more than twice what Trump paid for it four years earlier. Rybolovlev never occupied the property before demolishing it. He was the same man who sold a Leonardo da Vinci painting to Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for $450 million — a price that Epstein claimed was absurdly inflated. As Epstein noted, Rybolovlev “knows all”.

Last year, Rybolovlev appeared as part of Russia’s delegation in the Ukraine peace talks held in Riyadh, sitting across from Trump’s team. Just to be clear: the same man apparently involved in laundering money through a Trump real estate deal is now helping to negotiate the end of Europe’s largest war. One of the most spiritually exhausting elements of all this is that it’s impossible to discuss such things without sounding like a conspiratorial lunatic. But here we are.

As for Trump himself, Epstein described him in the emails as “the dog that hasn’t barked” — someone who knew all but stayed silent. Lutnick appears throughout as an obsequious dinner companion and fundraiser contact. William Barr, who repeatedly appears in the files, unilaterally cleared Trump of Russiagate charges in 2019. He was also Attorney General when Epstein died in federal custody. His father had given Epstein his first job at the Dalton School decades earlier.

But it wasn’t just Trump cronies. Kathryn Ruemmler, counsel to the White House under Barack Obama, wrote that she “adored” Epstein. Bill Gates met with Epstein repeatedly after his conviction for paedophilia. Bill Clinton flew on his plane. Noam Chomsky offered him advice. Larry Summers took his money.

The Russian collusion story was never about shadowy foreign forces assaulting an innocent democracy. This lets the US off the hook too easily. It was about a sphere of elite impunity. American consultants, Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes, European politicians, Israeli intelligence figures and British ex-spies all swim in the same waters.

Abstracted from the lurid details, Epstein and Russiagate are two manifestations of the same phenomenon. Epstein was a node in that global infrastructure and Russiagate was one operation that ran through it. You don’t need an elaborate conspiracy if you have lots of power and similar concerns.

Russia wants to weaken Western institutions and will pay for it. The borderless elite profit from weak institutions and enjoy getting paid. Their interests converge. At a certain altitude, the lines on the map disappear.

***

A version of this article first appeared on Hegemon.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe