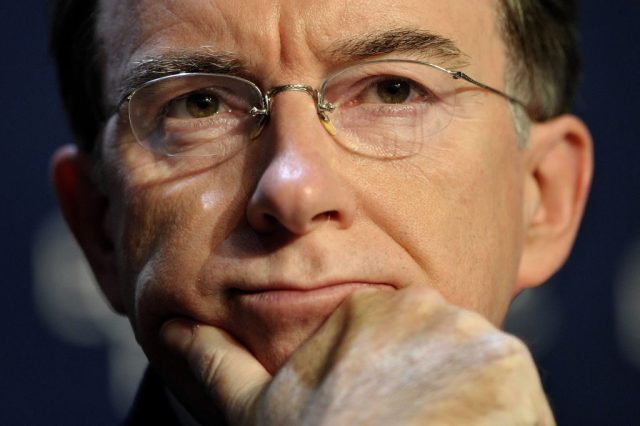

‘The tragedy of modern Britain is that Mandelson and his clique succeeded.’ (Credit: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty)

There is something of late-career Le Carré in Lord Mandelson’s latest fall from grace, beyond the fact that the villainous politician Aubrey Longrigg of Our Kind of Traitor, friend of oligarchs and corruptor of the body politic, is a vicious pen-portrait of Mandelson himself. Longrigg, “the most two-faced, devious, backsliding, dishonest and well-connected” of politicians, was for Le Carré “an archetype; a classic symptom of the canker that was devouring not just the City, but our most precious institutions of government”. The younger Mandelson, at least in print, would have shared the elderly writer’s moralising rage. “Not only does Parliament look corrupt, it appears weak and powerless,” the MP for Hartlepool advised in his well-received 1996 tract on the necessity for a New Labour government, The Blair Revolution, as “the respect in which politicians are held has been… damaged by the widespread impression that ‘they’re only in it for themselves’”.

As the architect of New Labour’s campaigning focus on Tory sleaze, warned his readers: the British voter’s faith in politics is squandered “when those who are elected to serve the public interest see nothing wrong in helping themselves to their own share of the consequent commercial rewards in directorships and consultancies. The idea that there is nothing objectionable about a public figure pursuing a dubious private commercial interest as long as it is declared is one of the most corrupting principles in public life today. As far as the electorate is concerned, many think we have a government that consists of business back-scratchers and a Parliament made up of politicians on the make.”

That two years later Mandelson was forced to resign for an undeclared loan from a parliamentary colleague, whose entanglement with the late press baron Robert Maxwell’s estate it was Mandelson’s remit, as trade and industry minister, to investigate, is more than just a piquant historical irony. After all, to have been once forced from office for perceived corruption and undue cosiness with the interests of the super-rich may just be bad luck. By the third instance, the blame surely falls to the employer: the character of the person involved is all too well-known, and the pattern long-entrenched. As Le Monde, freed from English niceties, characterises New Labour’s Third Man, he is “the evil genius of the British Labour Party”, a “tactician fascinated by fame and money” who “showed contempt for morality and common social rules.” The scorpion stings because that is its nature; the blinking protestations of the frog, clinging to the wreckage of his premiership, that such an outcome could not be anticipated are too absurd to be entertained.

Instead, the greatest, most ironic contrast that strikes today’s reader is not that between the younger Mandelson’s reformist, moralising tone and the well-established tenor of his political career, but rather the yawning gulf between his domestic reputation and the raw facts of wealth and power unveiled by the ongoing Epstein revelations. The notorious “Prince of Darkness”, the fearsome and powerful intriguer at the heart of British governance, stands revealed in his email correspondence as more Widmerpool than Machiavelli. Westminster’s ruthless operator, the terror of lobby journalism, comes across as a needy, social climbing arriviste, a grasping provincial striver dazzled by the opulent consumption of his rich friends and desperate to grab a slice for himself. So desperate, indeed, that his mentor Epstein even once rebukes him for his constant demands for favours. His New Labour memoir, The Third Man, sent to Epstein for writing advice, is, the two friends discuss, merely a CV for a role at Deutsche Bank. Epstein dangles other glittering prizes before his friend. Would Mandelson like to sell an Israeli oil field for Ehud Barak, Epstein enquires. Why not? Would Mandelson like to involve himself in post-Tahrir Square Egypt, Epstein wonders? Why not? The affairs of nations, once the engine of history, had at the End of History become mere business opportunities: it must have seemed, back in the 2000s, as if the party would never end.

The glittering, amoral world of Epstein and his associates, of the Russian oligarchs and Arab potentates and financiers who flit across the correspondence, is simply the end product of the world of globalisation, and of America’s unipolar imperial moment, without which the New Labour project is incomprehensible. When we read Epstein and Ehud Barak venomously gossiping over the extravagant income Tony Blair has amassed as the consigliere of Central Asian dictators, we are granted a glimpse of the true architecture of the world New Labour sold us as unstoppable progress. “We live in the new global economy, and that there is no alternative to that,” the Mandelson of 1996 advised his readers, and this is the result. Just like Blair, whose planned post-premiership career of resolving the Palestine conflict while accumulating wealth was rather more successful at the latter than the former, it was fortunate for him that this brave new world would transpire to be so personally rewarding. Epstein was nothing more or less than a vampiric aristocrat of American empire, extracting whatever he desired from its outer reaches. Mandelson his eager courtier, risen from that same empire’s provincial backwaters. How meagre and parochial British politics must seem from this exalted vantage point: it must have been hard to remember that the needs and desires of British voters ever mattered at all.

The age when a former prime minister could retire to obscurity in a quiet cathedral close ended with New Labour. Today, their second acts revolve around the imperial centre. As the German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck observes in How Will Capitalism End?, corruption, broadly defined, is simply a symptom of financialised capitalism in a globalised world, and the decaying social fabric of its host countries the result of a world in which “the rich may rightly consider their fate and that of their families to have become independent from the fates of the societies from which they extract their wealth.” If British industry did not notably prosper from Mandelson’s time overseeing it, smoothing its wholesale transfer into the portfolios of the globalised oligarchy, so be it. If the MP for Hartlepool more rapidly and dramatically prospered from New Labour’s time in office than did the people of Hartlepool, that is the nature of things. For all that Mandelson can proclaim that the business dealings with Epstein, for which the police are currently investigating him, were in “the national interest”, the governance of Britain does not figure in this worldview as anything other than a career first act, the highest offices of the British state merely a provincial dry run for advancement in the higher world, among the richer people, who actually matter. When even the former Prince Andrew inserts himself in Epstein’s court, seeking rest and relaxation from the onerous privileges of his sinecure, we see, if not the secret harmonies of the world, then its true architecture, beneath the Westminster state’s ornately crumbling facade.

As for the little people, the truculent and aggrieved British voters whose anger was to be assuaged by the scraps from the big table, redistributed as a consolation prize for the loss of their industries and the wholesale recomposition of their cosily insular society, if their time has not yet come, Mandelson’s third downfall is the harbinger of when it will. It is ironic to recall, now that the near-revolutionary tumult of British politics is waved away by the Government’s dwindling band of supporters as a false consciousness imparted by hostile Right-wing agitators, that the younger Mandelson once spun visions of Britain’s near future as dark as anything now found on Twitter.

Imagining the future world of 2005, in which the public had failed to vote a reforming Labour government into office, Mandelson in The Blair Revolution conjured dark prophecies of the forthcoming “millennium riots”, in which “the army had been brought in” and his fictional upwardly mobile family had witnessed “their neighbours running screaming along the road”, their Georgian townhouses set ablaze. As a result, “there had been a middle-class exodus from London to the Home Counties, into hastily built private estates with perimeter fences and private security.” In the real world of 1996, the “breakdown of society in Britain”, typified by “a crime wave [that] was dismissed as exaggerated tabloid scare-mongering”, derived from the simple fact that “the nation has been in relative decline for a century”, and was baldly “a declining, post-imperial, economically second-rank nation, which is also increasingly divided and unequal”.

In his introduction to the 2004 reissue of The Blair Revolution, Mandelson lamented Britain’s “bleak ghettos depressing the spirits of all who live in them, dominated by the fear of crime and racial tension, too often becoming centres of danger and desperation”, language now anathema to his ideological heirs. The British public had begun to despise its political class, he warned: “New Labour’s task now is to ensure that public opinion does not slip back into this sullen mood — or, at least, not permanently — and that a deeper, lasting connection is made between government and governed.” Does Mandelson feel New Labour achieved this, we wonder? Does he believe his wavering place at globalisation’s most-luxurious table is justified by the transformations his faction wrought? Mandelson termed his mission a “permanent revolution,” creating “a long-term transformation of Britain” in which New Labour’s ideology “embeds itself in the fabric and social architecture” so that “our changes can be entrenched”. Indeed, he notes, “We want to create institutions across British society that people can point to in twenty and thirty years’ time and recognise as distinctly New Labour landmarks.”

Indeed we can: New Labour’s monuments are all around us. The tragedy of modern Britain is that Mandelson and his clique succeeded. The wreckage of our society is a testament to the success of their project, a series of time bombs buried within Britain’s social and economic architecture. The Britain of 1996, the dismal object of Mandelson’s declinist rhetoric, now looks like a vanished golden age: an even partial return to it is the highest aspiration of Right-wing populism. The current prime minister’s project of governing Britain as if it were still 1997, taking off where his ideological forebears were so rudely interrupted by the British voter, was doomed from the start, because Starmer is fated to rule the volatile and rebellious country that New Labour created. The least popular prime minister since polling began is now condemned to eke out his mandate without power, at the helm of a fractious and moribund party that despises him, lurching from crisis to crisis, until the electorate’s final sentence of execution rescues him from his purgatorial reign.

A badly run country has become an ungovernable one, ill at ease with itself and looking inward for enemies. Lord Mandelson’s one, unintentional gift to Britain is in hastening the collapse of the rotten and crumbling superstructure of the politics he helped construct. The reams of internal correspondence soon to be released will provide Reform, the de facto party of opposition, with ammunition in its mission to undo the Blair Revolution Mandelson once flaunted. As the director of Labour Growth, Mark McVitie, rightly observes, the scandal is “the latest and most grotesque signifier of a political culture that cannot carry on in its current form”, and “what is undoubtedly worth saving in the liberal democratic settlement will not be saved by the people who have presided over its decay”. But the domestic tragedy of British dysfunction is inseparable from the country’s willed transformation into the fawning servitor of a corrupt transnational order. That it takes an American scandal to demolish the Government’s last lingering traces of legitimacy, our peripheral backwater administration haunted by the nefarious pleasures of its metropole, is only fitting. In his career’s final act Mandelson has become, just as Le Carré perceived, the squalid archetype for the British state itself.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe