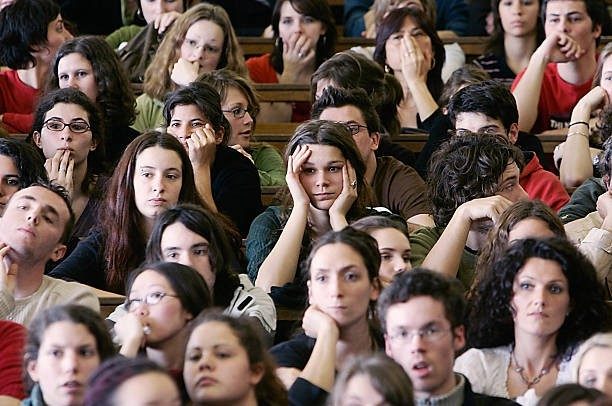

Are the kids alright? (Jean-Pierre Muller/AFP/ Getty)

I’ve been teaching in British universities for about 15 years and over that time, I’ve watched a few trends unfold. Like when they started needing safe spaces and denying basic facts about human biology. (That’s basically over now, by the way.) Or wearing hideous footwear, and dressing in androgynous black-and-white clothing. All of it the wrong size. (It’s not me that’s mistaken, it’s the kids.) But probably most noteworthy is the dramatic increase in students entitled to special accommodations because of disability.

Every year, more essays come in after the deadlines, because more students get extensions lasting weeks, even months. On Mondays I receive automated emails reminding me to be very careful when asking certain students questions in seminars, or expecting them to contribute in any way (apparently, they might not be able to handle it if I do). Despite the fact that I teach political philosophy — a subject impossible to execute without precise handling of language — the university bureaucracy says that the quality of written language needs to be disregarded when assessing some candidates’ coursework. All of this, and more, is due to accommodations made under the rubric of disability.

Last month, eye-opening statistics were published in this regard. From 2008 to 2023, the proportion of students at UK universities claiming to have a disability doubled from 8 to 16%. Even more strikingly, at Oxford and Cambridge it went from 5 to 20%. And the UK is not alone. As recently noted in The Atlantic, 38% of undergraduates at Stanford are now registered as having a disability. Lagging behind is Harvard, at “only” 21%. (Both were at 5% in 2009.) It’s the same across all developed Western democracies.

This explosion has not been driven by campuses suddenly becoming wheelchair accessible. (I happen to be a wheelchair user myself, and so I assure you that I take disability very seriously.) Instead, students are being diagnosed with impairment disorders relating to their ability to learn. And of these, four constitute the bulk: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and non-profound autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

So what is going on? The truth is, it’s complicated. And as a result, two of the most common answers just won’t do.

The first answer (which The Atlantic reporting leans towards) is that it’s basically all a scam. Here’s the thing: students with registered disabilities are eligible for deadline extensions, extra time during exams, and a whole raft of entitlements regarding seminar attendance and participation. Having realised that students with impairment diagnoses get such special consideration, sharp-elbowed middle-class parents reckon it is a sure-fire way to win their offspring competitive advantage. Shopping around for helpful diagnoses from pliant physicians, the aspirational classes respond to prevailing incentives. Cue the surge in presentation of the disorders.

To be fair, The Atlantic’s assessment isn’t completely wrong. Sometimes the lengths to which privileged parents will go for their kids are truly astonishing, especially in the United States. (Just Google “Varsity Blues College Admissions Scandal”.) Perhaps, then, we shouldn’t be entirely surprised to learn that the proportion of students entitled to extra time on exams has gone up significantly at UK private schools compared to the state sector.

I’m afraid, though, there is more afoot here than cynical families gaming the system — which certainly some will be. But let’s not forget that humans are complicated, fallible things and they have a peculiar predilection for seeking out evidence that confirms their pre-supposed conclusions. It is not that middle-class parents are pretending that their sons and daughters have these disorders. If their children are presenting as anxious and depressed and socially complicated, then they will really believe that their sons and daughters have ADHD and anxiety — these conditions have, after all, been confirmed by the professionals. Partly the reason they are more readily open to believing this is because the conditions no longer carry the heavy stigma they did in the past, when children would be institutionalised rather than sent to university. Rather than being a straightforward, limiting disability, the diagnosis now represents an opportunity: not just for extra time on exams, but also for handy legitimation and excuse-making if Junior comes up short (never mind extra bragging rights if he comes out on top). So while it is true that the middle classes have been responding to incentives, those incentives are more subtle and complex than simply trying to game the system.

For precisely these sorts of reasons, the other (and largely opposed) popular explanation for the increase in cases is also too simplistic: that rates of diagnosis have massively increased because medical professionals are now better at spotting underlying conditions which previously went unrecognised. While certainly the case in some instances, this cannot account for such massive increases.

To be clear, studies using consistent criteria of symptoms have found no increase in the incidence of those, even as diagnoses of ADHD and autism have simultaneously gone up dramatically. In short, people who would not have been diagnosed with those conditions 20 years ago are much more likely to be diagnosed with them today, even if presenting with the exact same symptoms. The threshold has moved. In the past, the level of symptoms required to trigger a diagnosis of something like ADHD or autism were higher than today.

So have doctors, psychiatrists, and other professionals become sloppy? Are they failing to properly apply the right diagnostic criteria? Is this a case of uncontrolled Nail Derangement Syndrome (to those possessed of hammers, etc.)? Have the forces of middle-class ambition and medical over-reach manifestly combined, to feed off each other? But again, this is too simple.

To understand the complexity of the issue, it is helpful to consider the work of the philosopher of science Ian Hacking, who spent much of his life trying to untangle this sort of thing. One of the most important lessons that Hacking taught us is that when it comes to medical diagnoses with behavioural aspects, humans are “moving targets”. This is because of what he termed “looping effects”: that when people receive a label, they respond to it by changing their behaviour accordingly. But because their behaviour has now changed, the label itself must evolve to capture the very thing purportedly being labelled. This then sets off new kinds of behaviour in those receiving the label — and thus the looping continues.

Hacking’s work on autism helps to illustrate the point. When autism was first established as a diagnostic criteria in the Forties, it applied only to the severely mentally impaired — typically those who were non-verbal and highly socially dysfunctional (they were unable to live without extensive support provided by parents and professional carers; many were institutionalised). Over time, however, the criteria were relaxed, in particular the (controversial) introduction of Asperger’s syndrome in the Eighties, which applied to “high functioning” autistic people especially: those who were not only fully verbal, and often living independently, but crucially were diagnosed as adults (previously autism was something identified almost exclusively during childhood, precisely because it was so severe).

Yet this expansion of autistic criteria and the birth of the idea that autism is a spectrum, rather than a single category of psychological impairment, inevitably set off looping effects. An Asperger’s diagnosis, for example, changed not only the way certain kinds of adults (i.e. those receiving the diagnosis) viewed themselves, but how they behaved. Rather than being shamed and shunned for being “weird” (the fate of earlier generations), they could now (justifiably) protest that they were simply different, as validated by science, and deserving of relevant accommodations. Indeed, many advocated for precisely this distinction, refusing to suppress their non-typical behaviours simply to accommodate “normal” people. (This is one important origin of the modern distinction between the “neurotypical” and the “neurodivergent”.) Such a development has quite clearly benefited, in real and important ways, many people, allowing them to access better resources in a world of reduced stigma.

Yet, as the criteria was relaxed, more and more adults started to see themselves as possessing features enveloped within the ever-growing “autistic spectrum”. Ever-growing, because the spectrum diagnostics kept changing to incorporate and accommodate the growing range of correlated symptoms. Which led to more people meeting the criteria, and so on.

This itself is an oversimplification. But it is a large part of why we now have an “autism spectrum disorder” so broad that I can have students medically diagnosed as autistic, and yet who have rich social lives, romantic partners, and no problem understanding (and sometimes even laughing at) my terrible jokes in lectures. Autism today means something radically different from what it did in the Forties, or even the Eighties. The looping effect has moved the targets.

But that’s not the end of the story. There is, also, an interconnected phenomenon, which Hacking called “making up people”. His point is that there are certain ways to be a person that require a pre-existing social infrastructure to first be in place.

I can illustrate by taking the example of a skater. The casual reader might think that this is simply somebody who rides around on a skateboard. But there’s much more to it than that. To be a skater is to identify — and be shaped by — a certain subculture. When I was a teenager, riding around on skateboards was almost a secondary feature of being a skater. Arguably more important were things like listening to punk music, wearing baggy jeans, smoking weed, and rejecting authority. We were outsiders and liked it. We were consciously anti-cool. But, then, everything shifted. The X Games aired on TV and Tony Hawk became a household name with his PlayStation game (owned by everybody, including the non-skater kids at school who used to bully us skaters). As a result, what it meant to be a skater evolved: it went mainstream and became sort of socially acceptable, which radically changed what it was. The looping effect kicked in. Now when I go to the local park, I see men in their thirties happily grinding the rails alongside schoolchildren. Not a single mohawk in sight. Nobody is even smoking weed. Being a skater ain’t what it used to be.

The point is, being “a skater” was only possible not just after the boards were invented, but after skateboarding became affiliated with a type of youth counterculture, itself evolving over the decades.

On Hacking’s account, the same is true of “high functioning autism”. While it is certainly true that there have always been people possessed of literal mindedness, a fixation with niche interests, difficulty relating emotionally with other people, finding it hard to read social cues and so on, it was only roughly 40 years ago — when it was diagnosed as a medically recognised thing — that you could identify as a “high functioning autistic”. It became a social role that people could inhabit. And which they could eventually expect others to recognise and accept.

The modern explosion in ADHD diagnoses, then, can be understood in pretty much the same way. When I was an undergraduate in the mid-2000s, ADHD was something the naughty kids who failed at school all had. As a consequence, back then it was almost impossible to imagine an Oxford PPE-ist with ADHD. The social infrastructure required to conceive of an academically high-achieving student with such symptoms was not yet in place. Now it is. This in part explains the striking changes of recent years: we have been “making up” new kinds of people.

I don’t think we got it “right” back in the 2000s, and that since then everything has been going to the dogs. Some things are definitely better than they used to be. As somebody who has battled with clinical depression his entire adult life, I much prefer the open acceptance of mental health that is a feature of universities today, as compared with the world I grew up in. But we can still usefully ask: are we making the most effective use of our resources?

I’m doubtful. For a start, the increase in diagnoses has not translated into effective help for those who need it most. A few years ago, I had a student diagnosed with a form of autism which impaired her life in serious and very evident ways. She was fully aware of the things she needed to do to mitigate the very real disadvantages her condition generated. But she had to battle for every scrap of support she could get because she was competing with dozens and dozens of other students, who on paper were entitled to the same levels of disability support, but that no reasonable person would put in the same bracket.

More generally, there is the question of whether widespread special learning accommodations are hindering rather than helping our students. University administrators love to bang on about imparting “transferable skills” to undergraduates. What they normally mean is nebulous guff such as “communication”, “leadership” or “problem-solving”. By contrast, here are some real transferable skills: turning up on time, meeting deadlines, having to manage multiple tasks at once, dealing with intellectual discomfort, pushing through and completing something even if you find it boring, difficult, or unpleasant. In short: learning when you have to suck it up and grind on, because sometimes that’s just how life goes.

And yet diagnoses like ADHD, anxiety, depression, and ASD — and the attendant accommodations put in place — allow students to avoid having to learn these difficult life skills. Nor can we lecturers hope to impart the importance of short-term toil for long-term reward: tough love and all that. Who are we, after all, to contradict medical diagnoses, not least when vast university bureaucracies are now structured to uphold and defer to such things?

There’s no small irony to all this. Measures originally undertaken with the good intention of helping students may be doing the very opposite. The road to hell, and all that. It’s time to loop some different effects, make up some new kinds of people.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe