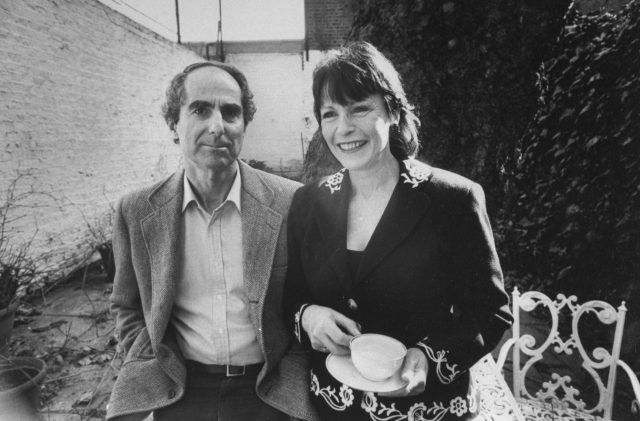

Philip Roth and Claire Bloom, 1990. (Ian Cook/Getty)

There is a fairly standard protocol governing the deaths of great novelists. First, there is a large memorial event in New York — it’s always in New York, whether the writer was born in Westchester or West Papua — at which the dead novelist’s celebrity-writer friends congregate, eyeing each other like ladies at the Venetian opera and wondering who will be the next out the door. Then come the obituaries, all of them glowing, disparagement stowed away behind words like “complicated” and “human”. Finally, after a period of two or three years, the great writer will undergo his or her final transubstantiation into a well-received literary biography, of massive length and usually scant readership.

For a while, it looked as if Philip Roth was going to adhere to this protocol rather neatly. When he died in 2018, his memorial event at the New York Public Library was attended by Salman Rushdie, Don DeLillo, Mia Farrow; in the weeks that followed, even the most politically hostile obituarists were forced to admit that Roth had been the most important American writer of his generation. Blake Bailey’s 900-page Philip Roth: The Biography was published in 2021, to gushing acclaim from reviewers as distinguished as Cynthia Ozick and David Remnick, and, more importantly, a place on the New York Times bestseller list. It was a big, brash, bawdy celebration of the writer, who, if turbulent love affairs and glamorous friends are considered a reliable metric, had done more living than most.

Then, in April 2021, disaster struck. At what was just about the height of the MeToo movement, worrying rumours began to circulate about Roth’s biographer. Bailey, it was alleged, groomed young girls for sex at a high school where he taught, and later raped two women. Soon, the story had reached national newspapers; Norton, Bailey’s publisher, had his book pulped. Within a few weeks, however, the discourse had taken an unusual turn. Much of the criticism left Bailey behind entirely and instead turned its attention on Roth himself. “A best-selling biography of a misogynist, written by an alleged abuser, is almost too apt a metaphor,” wrote one journalist. “Philip Roth and His Defensive Fans Are Their Own Worst Enemies,” read a headline in The Nation. It was no wonder, so the allegation went, that Roth had chosen a predator as his biographer. Had they not read him? His novels were littered with wife-beatings, underage seductions, extramarital affairs. He was, everyone suddenly seemed to agree, the misogynist’s laureate.

Roth Studies are yet to recover from this commotion. If you want to get a Roth biography published these days, you have to strike a rather coy, apologetic tone. This, at any rate, is the tactic pursued by Stephen J. Zipperstein in Philip Roth: Stung By Life, published by Yale University Press this week. Yes, Zipperstein argues, Roth did have a lot of sex, but he was first and foremost a writer; the biographer, therefore, must put aside his prurience and focus on the work itself. Accordingly, Stung By Life passes over much of the juiciest gossip that surrounded Roth in dignified silence, and instead offers long, slightly staid summaries of the novels. The success of the biography — and, indeed, the future of Roth’s reputation — appears to be staked on a very old question: to what extent, when all is said and done, is it possible to separate the art from the artist?

Once the problem is framed in this way, it is hard not to be pessimistic about the prospects for both the Roth biography and the Roth brand. Roth was, after all, a compulsive literary self-examiner and self-mythologiser: at least three of his novels contain a character called “Philip Roth”, and a full nine involve Nathan Zuckerman, whose Jewish upbringing in Newark, New Jersey, relationship with his father, succès de scandale with a ribald early novel called Carnovsky, and litany of physical and mental afflictions are clearly modelled on Roth himself. His first real blockbuster, Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), took the form of one long psychoanalytic confession, full of ungenerous family sketches that most readers took as barbs against Roth’s own parents, and a memorable defilement of a piece of liver that led one writer to muse on The Tonight Show — clearly showing where she came down on the issue of separating art from artists — that “Mr Roth is a fine writer, but I wouldn’t want to shake his hand”.

Poring over early interviews with Roth, it is impossible to ignore the sheer frequency with which the question of biography comes up. Following the publication of his first truly great novel, The Ghost Writer (1979) — which sees a fictionalised Roth (Nathan Zuckerman) undertake literary pilgrimage to a fictionalised Bernard Malamud via a fictionalised Saul Bellow — almost every interviewer feels the need to open with the same salvo of inquiries: “Are you Zuckerman?” “On which one of your stunning girlfriends is this woman modelled?” “How do your parents feel, knowing they have been so mercilessly stitched up?” Roth, of course, always rebuffs the questions: life is life, and art is art, and any conflation of the two is just readerly laziness. Still, it is hard, reading over Roth’s back catalogue, not to conclude that these conflations and confusions were not at least part of his aesthetic master-plan. Roth was particularly fond of quoting Czesław Miłosz’s aphorism that: “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.” When Roth picks up his pen, reads the hidden admonition, no-one in his life is safe.

There is a case to be made that Roth’s early novels tend to be successful in strict proportion to how much they cannibalise his life and relationships. To my mind, The Counterlife (1986) is the best of the bunch — yet it is difficult to imagine reading this book without some sense of what kind of creature Roth was. After all, in many ways, it is a novel about how mad, neurotic, possessive and irresponsible writers can often be with the other people in their lives. The general conceit is straight out of Pirandello: one by one, the characters in Zuckerman’s work — his brother, Henry, and Maria, the young woman upstairs with whom he has been having an affair — start rebelling against the author who controls them.

In the final section of The Counterlife, Zuckerman moves to England, and begins to dream of a peaceful, domestic existence with Maria, holed up in her flat in Chiswick with a baby on the way. But he can never permit himself this pleasure; he is too insistent on injecting conflict, neurosis, plot, into everything he touches. “You are forty-five years old, and something of a success,” says the exasperated Maria: “it’s high time you imagined life working out.” She does not get her way. Of course she doesn’t: she has fallen in love with a writer, and to the writer, people are just raw material, pawns to be pushed around on a board. “At the point where ‘Maria’ appears to be most her own woman, most resisting you, most saying I cannot live the life you have imposed upon me,” she exclaims in her final letter to Zuckerman, “she is least real, which is to say least her own woman, because she has become again your “character,” just one of a series of fictive propositions. This is diabolical of you.”

A few years after The Counterlife was published and showered with awards, one of the characters in Roth’s real life began to rebel, too. Claire Bloom, Roth’s English ex-wife, who had suffered through The Counterlife’s composition alongside him, released her own account of their marriage. Her ex-husband, she wrote in her wildly successful memoir Leaving A Doll’s House, was not just a neurotic and a valetudinarian, but a gleeful saboteur of every good thing in his life — cruel to Bloom’s daughter, downright libellous to her family, and all for the simple reason, as she saw it, that “too much harmony had become an obstacle to his creativity”. Almost no-one believed Roth’s side of the story — after all, he had just won the National Critics’ Circle Award by casting himself in much the same light.

What is the partisan of “separating the art from the artist” to make of all this? Clearly, Roth’s work cannot really be fenced off from the unsavouriness of his life; it is effective, in large part, because it appears to be a product of that unsavouriness, the spontaneous emanation of a deeply flawed soul. Does that mean, then, that projects like Zipperstein’s are futile? Or is there another way to advance biographical criticism without just resolving into a moralising whine?

Perhaps we should look to Roth’s own work for guidance. When I read the novels Roth produced in the aftermath of his marriage to Bloom, I am struck by the influence of one writer in particular — not the well-known ur-Roths like Saul Bellow, Kafka, and Henry James — but Louis Ferdinand Céline, a frothing antisemite, Nazi collaborator, pervert, misogynist, and plausible candidate for the most evil writer of the last century. Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater (1995) sometimes reads almost like a pastiche of Céline: a debauched Jewish puppeteer named Mickey Sabbath rages, mourns, copulates, blasphemes, desecrates with a relentlessness that rivals even great Célinian protagonists like Bardamu and Ferdinand. Even Martin Amis — himself not exactly shy about putting the odd male monster in his fiction — admitted he found the character “rebarbative”.

In a sense, though, Céline rescued Roth. Smarting from Bloom’s revelations, wary of his growing number of feminist critics, the most indignant man in American letters could have easily retreated into a kind of prickly vanity, a defensive management of reputation. Céline, however, showed him that redemption could be sought in a kind of anti-vanity — that great things could be achieved by an artist who was prepared to cultivate a bad reputation, to deform his own personality into horrific shapes, just to make his work seem all the more stirringly grotesque. In an interview with The Paris Review, Roth explained the method. There were saving graces in Céline’s life: his diligence as a doctor, his work with the League of Nations. “But that wasn’t interesting,” said Roth. “His writing drew its vigour from the demotic voice and the dramatization of his outlaw side (which was considerable), and so he created the Céline of the great novels.”

This, I suspect, is what both Roth’s moralising detractors and formalist defenders miss. Whenever we feel tempted to moralise about Roth’s life, we have to ask ourselves: is this not, on some level, part of the trap he has laid for us? Does he not, deep down, want to be abhorred? Perhaps this is the true value of the newer, “boring” Roth biographies: they remind us that in many ways, Roth the monster was just as much a creation as Roth the distinguished man of letters. Reading Zipperstein’s book, it is hard not to conclude that though Roth left lots of disgruntled women in his wake, the overwhelming majority accused him not of philandering, or deceiving them, but of being selfish — completely unwilling to compromise on his literary efforts, unwilling to surrender even an hour that could be whiled away in his study to anyone. If you wanted to spend time with Roth, it seems, this was something you just had to accept. Your life would be raided and bowdlerised, your family slandered, your most intimate moments submitted by his publisher to the National Book Award committee.

Perhaps we should condemn Roth for this. There is something genuinely deranged about someone who is prepared to deform themselves for the sake of a novel or two, and who treats everyone who crosses their path as raw material for their act. Still, it is stirring, especially in an era when reputation-management rules, when books are pulped for their author’s alleged impropriety and publishing becomes ever more indistinguishable from public relations, to witness one writer be so willingly scandalous, viewing his reputation as an addendum to his art, and not the other way round. If Philip Roth really was a control-freak, obsessed with manoeuvring everyone in his life into the narratives he had ordained, then this was not out of vanity, but out of artistic single-mindedness. Any behaviour was permissible, so long as it made the Philip Roth Show appear even more dazzling. In this respect, he had a streak not just of Céline, but of the greatest Jewish writers, of Moses and Jeremiah and Maimonides: he knew, deep down, that the flesh is nothing, compared to the word.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe