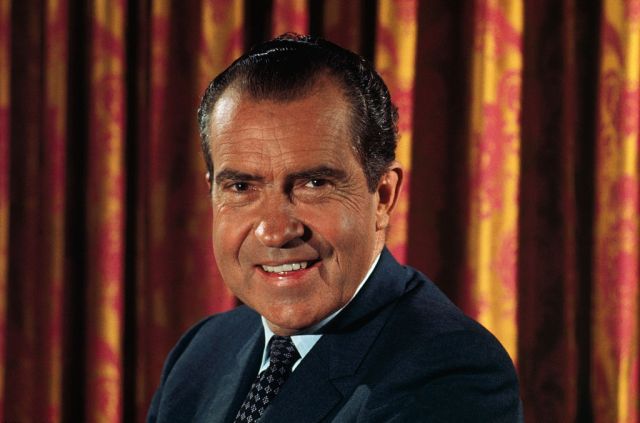

‘TikTok Nixon is a man of honour, an idealist, a gifted statesman.’ Getty Images

Dead presidents rarely go viral. There are, of course, glorious exceptions — listen, for instance, to LBJ pleading for slacks that don’t “cut me like a wire fence”, or JFK ranting about furniture (“Well, this is obviously a fuck-up”). By and large, though, the content circulating about postwar commanders-in-chief is worthy but dull, fascinating to US history buffs but never containing anything that might shift the needle on their historical reputations.

Except Richard Nixon. Recent years have seen the 37th president’s social media profile transform from the familiar Tricky Dick to far more rarified heights. TikTok Nixon is a man of honour, an idealist, a preternaturally gifted statesman armed with acerbic insights into the power of the American media and eerily accurate predictions about the present-day state of Israel, Russia and China — at turns sentimental, even gossipy, but always the doughty defender of the common man.

Not that this is merely a story of some online tickers going steadily upward. On the contrary, Nixon’s social media revival matters in the grubby politics of the here and now. In an age of polarisation, and one in which the young are increasingly disenchanted with democracy itself, the growing lionisation of the only commander-in-chief to resign in disgrace is a red flag for the republic’s future.

At first glance, Nixon’s online persona is remarkably gentle. There’s a good reason for this: most clips are spliced from soft-soap post-Watergate interviews, when Dick was relaxedly hawking foreign policy tomes that, according to biographer Evan Thomas, were “moderately interesting and sold moderately well”. This is Nixon at rest, keen on sharing homespun wisdom about a life spent in service between his verdicts on Mao and the Shah. “What makes life mean something is purpose — a goal, the battle, the struggle,” he says in one such clip. “Even if you don’t win it.”

Spend time in Nixonworld, though, and you’ll quickly spot clips far more brazen in their admiration for Tricky Dick. See, for instance, the excerpts from Mad Men in which Don Draper is suddenly captivated by Nixon’s 1969 inauguration address, or when he waxes lyrical about the Republican’s hardscrabble journey to the vice presidency just six years out of the navy — all before that familiar burr interrupts our regular viewing with a series of smash cuts.

Such lionisation makes sense if you know where most of these clips come from: the Richard Nixon Foundation, the co-owner of the former president’s library in Yorba Linda, California, and an organisation for which the sentence “it was just a burglary” is considered a fair summation of his legacy. The past year has seen the institution not only become an increasingly Trumpy meeting place for the GOP’s great and good, but also such an effective proponent of Nixon across social media that it’s booted many of the spicier White House tapes off the top tier of YouTube search results — and increased its subscriber base by 236%.

For the Nixon connoisseur, this is the historiographical equivalent of seeing the ex-president’s bullfrog jowls gurning through a beachside bodybuilder cut-out. Elements of the overall image are recognisable: Nixon’s mastery of foreign affairs, for example, or his deep-seated suspicion of the media. Yet absent from the picture is the racism, the homophobia — and, let’s not forget, the crimes.

Who watches this stuff? Despite the Boomer flavour of many of the foundation’s in-person events — you, too, can celebrate “the women and girls in your life” with a Title IX fun run — the audience most receptive to the new, hunky Nixon appear to be young, conservative-leaning voters occupying an increasingly polarised media landscape. Raised on a steady media diet of diverse perspectives, fractured across multiple social media platforms (usually TikTok), members of Gen Z are more cynical and anxious than their parents. They also find mainstream news brands increasingly untrustworthy, with only 56% of 18-29-year-olds having a “lot” or “some” trust in national news organisations. That’s down from 62% in 2016, a decline that’s even more pronounced among Millennials.

That mistrust is sharper still among young Republicans, an increasing number of whom wholeheartedly trust the news they consume from social media. Among this cohort is the intellectually impressionable manosphere, for whom Nixon has become a cause célèbre, an appeal that makes sense if you consider the former president’s image of himself as a complex loner misunderstood and maligned by the liberal establishment.“I didn’t know, until Tucker explained it on the show, about Nixon,” podcaster Joe Rogan said last June, referring to a conspiracy theory suggesting that Bob Woodward and the CIA framed the then-president for Watergate. “Nixon, who’s the most popular president in history — that was a government-orchestrated coup!”

As Carlson’s characterisation of Nixon implies, it’s easy to see him as a Seventies stand-in for Donald Trump offline too, with both men the undeserving victims of a snobbish liberal establishment determined to preserve its monopoly on power at the expense of the hardworking American public. Republicans are also enthusiastic in echoing Nixon’s dictum that “when the president does it, that means it is not illegal” whenever they feel duty-bound to defend the former businessman (turns out, it mostly isn’t.) One good example is Ted Cruz, who has argued that democracy should be decided “at the ballot box” — even as Republicans tried to overturn the 2020 election.

It’s a superficially appealing comparison. Much has been written comparing presidents 47 and 37, mostly about their animosity toward the press, women, ethnic minorities and the rule of law. Similarities in their personalities is also a popular topic. “There is a volcanic centre to both men: the ranting, the anger, the paranoid concerns; the hatred,” is how historian Timothy Naftali put it in 2018, speculating that Trump could yet engage in dodgy “Nixonian” behaviour.

They certainly liked each other. “I think that you are one of this country’s great men,” Trump wrote to Nixon in 1982, a few days after the pair had been spotted together at a dining club in New York City. In a series of exchanges, and over the course of one beautiful night in Houston, the two discussed everything from the New Jersey Admirals to the importance of using crowds as “props” during rallies. Pat Nixon even hoped The Donald himself might run for political office in future. “As you can imagine, she is an expert on politics,” wrote her doting husband, “and she predicts that whenever you decide to run for office you will be a winner!”

Trump had that letter framed, later promising he’d hang it in the Oval Office. It’s unclear if he ever did — or indeed whether it served less as a source of inspiration than a warning of what not to do in the White House. At the height of the impeachment speculation, during his first term in 2019, Trump asserted that he wouldn’t suffer the same fate as his long-dead predecessor because he’d never be cowardly enough to resign. Similarly, the 47th president bemoaned Nixon’s reluctance to let wayward staff marinate in their own insubordination before firing them. In fact, a plausible argument can be made for Trump seeing Andrew Jackson, not Tricky Dick, as his primary presidential inspiration. After all, it’s Old Hickory’s portrait, not Nixon’s letter, that takes pride of place in most Oval Office photo ops.

But if Trump himself has left Nixon behind, his acolytes clearly haven’t. “When it comes to foreign policy,” intoned Vivek Ramaswamy during his abortive run for the GOP nomination in 2023, “the president I most admire is Richard Nixon.” The Californian’s canny insights into the Russian psyche have routinely been cited as inspiration by conservative activists for ending the war in Ukraine, a possibility left unexplored by the Biden administration. “My answer to this whole proposal of […] whether or not the Russians can be trusted is very simply: only if we make agreements which are in their interests to keep,” Nixon told one interviewer. It’s a lesson Trumpworld figures have been more than happy to absorb. “If we aren’t careful,” said ex-Trump advisor Steve Bannon, “it will turn into Trump’s Vietnam. That’s what happened to Richard Nixon. He ended up owning the war and it went down as his war, not Lyndon Johnson’s.”

Ultimately, though, these comparisons can only be taken so far. Trump’s tariffs, and his meetings with Pyongyang’s pound-shop Mao, compare poorly to the scale of the Nixon administration’s achievements in rebuilding US credibility while pretending not to lose in Indochina. That’s because the global outlook of the two men is fundamentally different. Where Trump leads his country abroad as if he were still a rapacious Eighties landlord, Nixon knew that US power rested on leveraging its fragile position as primus inter pares.

There are, of course, other obvious differences. Where Nixon was personally brave, enlisting in 1941 despite his Quaker faith, Trump said avoiding catching STIs during the Nineties was his own “personal Vietnam” — even as he received a dubious bone spur diagnosis to avoid being drafted into the real thing. Where Trump has made the term “braggadocious” part of his personal brand, meanwhile, Nixon was so socially awkward that he couldn’t look his doctor in the eye and felt duty-bound to apologise to his researcher for chuckling at The Dick van Dyke Show.

All the same, one very obvious similarity between the two men lies in their hatred of what Nixon called the “liberal establishment” — with the former president cited as a source of inspiration among conservative thinkers. Leading the charge has been self-styled Right-wing Leninist Christopher Rufo, who, when he’s not drafting lesson plans for teachers in Florida, argues for Nixon’s elevation as the spiritual father of the modern Republican Party. The ex-president “set the stakes for the American public and established themes that still dominate American politics today,” Rufo wrote in 2023.

According to Rufo, Nixon’s plans to overhaul the bureaucracy; reestablish law and order by smashing Left-wing radical groups; and create a conservative “counter-elite” to supplant liberal reporters form an ideal blueprint for rebuilding America. The result, the activist argues, would be a truly “pluralist republic” that prizes “excellence over diversity, equality over equity, dignity over inclusion, order over chaos”.

It’s a vision of America that the GOP has been grasping at since 1968 — but one that the conservative movement is closer than ever to achieving. Nixon’s crusade began in the mid-Sixties, in an America that was, though wracked by protests, violent crime and racial segregation, still enamoured by a liberal consensus that kept Tricky Dick’s coattails short in 1972. He may have smashed George McGovern in a landslide, yet both Republicans and the public at large quickly turned against him once the full scope of the Watergate scandal came out. Now, though, the GOP dominates all three branches of the US government, egged on by a Right-wing media machine pushing it to erode the ability of its opponents to nominate judges, prevent gerrymandering, exercise the right to vote, or even guarantee a safe transition of power.

Poor Richard. While Nixon was never slow to see opponents in every corner, and certainly wanted to politically sideline as many as possible, these actions were never consciously undertaken to undermine democracy. Were he alive today and somehow operating in our political landscape, maybe things would be different. As Geraldo Rivera ruefully told Trump-supporting presenter Sean Hannity in 2019: “Nixon never would have been forced to resign if you existed in your current state back in 1972, ’73, ’74.”

Surely, though, the emergence of a new Nixon as a conservative Jeremiah is bad enough for the health of the republic. While the White House incumbent is not powerful or motivated enough to kick away the safeguards preventing him from assuming the purple, the 47% of Americans who consider a second civil war is inevitable probably think a figure like that may soon emerge. By then, voters won’t have a Nixon type to kick around anymore, but instead someone far more dangerous.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe