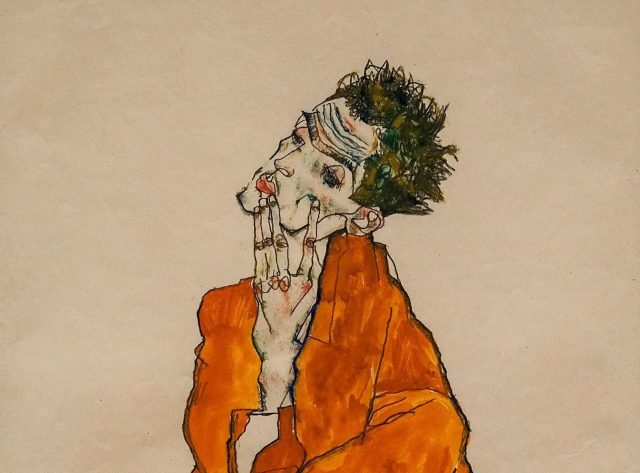

Albertina Museum, Vienna, Austria.

Even if you haven’t read Robert Musil’s unfinished modernist masterpiece, The Man Without Qualities, you probably agree that it has a great title. If you have read it, I’m sure you agree, because the novel returns obsessively to the theme of how its main character, Ulrich, can’t quite get his act, or, more fundamentally, his personality, together. But I’ve come up with an even better title. I think Musil should have called his novel The Man Without Philosophy.

I acknowledge, in offering this improvement, that over the course of the novel Ulrich explicitly espouses a life-philosophy; moreover, he even fashions his own name for this philosophy, “essayism”. Essayism is a mode of living whose characteristic expression is a stretch of novel and insightful reflection, “explor[ing] a thing from many sides without encompassing it”. The essayist lives a life of thoughtful observations. Ulrich lives that life, and so does Musil, who is much more interested in filling his novel with thoughtful observations than with any of the usual contrivances of plot or character development. Ulrich recoils against being “a definite person in a definite world”, and instead leverages his mind’s bottomless capacity for re-evaluation to emulate the infinite changeability of “a drop of water inside a cloud”. Ulrich describes his relationship to ideas: “they always provoked me to overthrow them and put others in their place.”

For Ulrich, as for Musil, “there was only one question worth thinking about, the question of the right way to live.” Isn’t that, in its very essence, a philosophical project? Yes. But there is good reason, nonetheless, to insist that Ulrich is a man without philosophy, namely, the fact that both Musil and Ulrich insist on it, over and over again. Ulrich acknowledges that in his predicament, “he could have turned only to philosophy” but the problem was that philosophy “held no attraction for him”. Again and again: “he was no philosopher.” He took a “somewhat ironic view of philosophy”, because, decades before the novel opens, he had already given up hope of actually finding the right way to live: “our thoughts cannot be expected to stand at attention indefinitely any more than soldiers on parade in summer; standing too long, they will simply fall down in a faint.” The result is that “he was always being provoked to think about what he was observing, and yet at the same time was burdened with a certain shyness about thinking too hard”.

Thinking hard makes sense if you want answers; it makes less sense if the highest reward you anticipate from your intellectual efforts is surprise. The difference between a philosophical life and an essayistic one is that the former aims at knowledge, while the latter aims at novelty. The characteristic positive response to an essay is: “I hadn’t thought about it that way before”; the essayist’s chief enemy is boredom. Ulrich “always did something other than what he was interested in doing” to ensure his unpredictability, even to himself. The essayist is a responsive, reactive creature, always aware of the standard way of looking at things, and always on the alert for the path of least resistance to some alternative point of view.

In Musil’s telling, the life of an essayist is a tortured one, because it is the life from which philosophy is, not only absent, but, much more specifically, missing. When you look at Ulrich, all you see, at first, is a glib intellectual who smiles at his own clever reflections; but eventually you discern that beside this cheerful and self-confident man there walks, as Musil calls him, “a second Ulrich”. The second Ulrich, “the less visible of the two”, is “searching for a magic formula, a possible handle to grasp, the real mind of the mind, the missing piece,” but he is struck dumb, unable to find any words to express himself. Musil says this man “had his fists clenched in pain and rage”. Ulrich the philosopher is trapped inside Ulrich the essayist.

Musil himself turned down an academic job in philosophy, much to the chagrin of his family, in favour of writing a book of thoughtful observations. The book, and the character of Ulrich, show us what it is like to be a thinker without a quest: perpetually idle in spite of all one’s ceaseless, restless intellectual activity.

Ulrich is a serial womaniser whose relation to women is analogous to, and therefore gives us insight into, his relation to ideas. Early in the novel he describes an evening with one of his lovers using two images: the first is a “ripped-out page” from a book. The evening, although enjoyable, didn’t connect to any larger narrative. Ulrich was not looking for a wife, or to start a family; he just likes being around them, until he doesn’t — and this means that his romantic evenings fail to add up, like a series of vacations. The second image, even more striking, is that of a tableau vivant: a frozen drama, where actors pose motionless to recreate a famous scene. Imagine, for example, an actress playing the role of Medea standing over her children with a knife. Musil describes such a moment as “full of inner meaning, sharply outlined, and yet, in sum, making absolutely no sense at all”. The tableau vivant makes no sense because you would never hold a knife like that, still, poised, hovering over someone: that position only makes sense in the context of other positions, into which it is integrated as a motion. This is an apt description of what happens when ideas are forced to do the work to which they would only be suited if you did not remove any possibility of ever “wholly encompassing some subject matter”. When you chop human love, or human thought, into pieces, the effect is similar to chopping a human body into pieces: horrifying.

Musil fought in the First World War; during the Second World War, the Nazis banned his books and he lived in exile with his Jewish wife in Switzerland. He died in 1942, leaving The Man Without Qualities, which he had been obsessively revising for decades, unfinished. It is a remarkable fact about the novel that Ulrich, Musil’s alter ego, sets foot in neither war. The novel opens in August 1913, and in over a thousand pages it never manages to traverse the 11 months to the start of the First World War. Musil knew something of the atrocities of dehumanised modern warfare and the brutality of totalitarian oppression, but they were not his subject matter. Instead, he wanted to report, firsthand, on what he had seen earlier, back when times were supposedly good, a realisation so disturbing that not even two subsequent world wars could distract him from it: “there is just something missing in everything.” In bad times, short-term goals crowd your field of view; it is precisely when times are good that you are in a position to take a step back and notice that the big, long-term goal, the one that is supposed to hold everything together, is what has gone missing.

I read The Man Without Qualities for the first time when I was in graduate school in Classics, and within a year, I had left that programme and switched to philosophy. Why, given that I had been devouring philosophical texts since high school, didn’t I major in it in college, or pursue it after college? I don’t think I could have put it this way at the time, but: I was afraid. The fear was partly an insecurity about myself — that I wouldn’t measure up, that I had nothing to contribute, that I was not worthy to walk the esteemed corridors of philosophy — but the other part, the deeper part, was a fear about philosophy. I was afraid that if I looked carefully, I would discover that there really were no answers out there. As long as I never tried to find the right way to live, I couldn’t definitively say it didn’t exist. I’m not claiming that Musil reassured me that it did. No, what The Man Without Qualities gave me was a vivid and terrifying glimpse of the life of thoughtful observations; Musil was my ghost of Christmas future. I would have to, somehow, find in myself the resources to believe that inquiry was possible, both for human beings in general, and for me in particular, because, as scary as the prospect of failure was, I had just seen something scarier.

You could think of a mind as having a dial that is usually turned way down, except on those occasions when we need to solve a specific problem, but even then, we only turn it up a little. What would happen if you set it to maximum, all the time? It would chew through everything — through our usual self-justifications, through the conceit of inevitability that attaches to our habits and customs, through the thin scaffolding of reason that holds life together. Such a mind would become, as Ulrich once describes himself, “a machine for the relentless devaluation of life”. The only way to avoid this result is to give the mind a task worthy of its powers, by presenting it with the sorts of questions one can, without shyness, think hard about. But that entails some hope of arriving at answers. This is one way to think about philosophy: a safe space for the unfettered operation of mind.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe