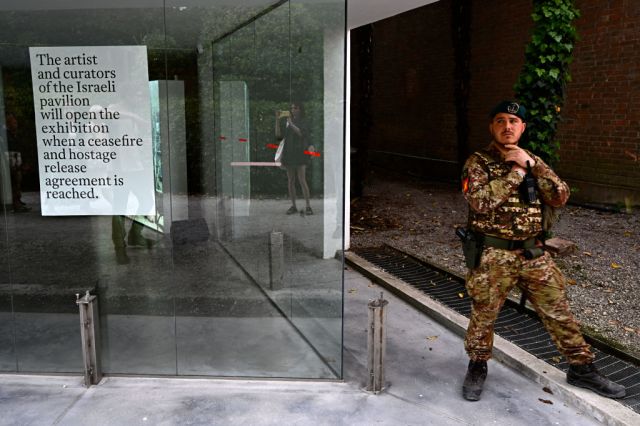

The closed Israeli pavilion at the Venice Biennale (Photo by GABRIEL BOUYS/AFP via Getty Images)

Venice during the opening week of the Biennale is the epicentre of the art world. Dealers rub shoulders with artists, sharing champagne and taking speedboats to after-parties in decaying palazzos. It is, at once, glamorous and intoxicating.

In theory, this is because of the art — the hard-hitting, big-statement, generously-funded art. It’s supposed to be a celebration of excellence, an opportunity for countries to showcase the heights of their culture. But what happens when this is no longer the case?

With this year’s theme, “Foreigners Everywhere”, the cultural status quo of the last few years became crystallised. Identity politics and decolonisation ruled above all. The Spanish pavilion showed a Peruvian artist who spoke about historical colonialism; the American pavilion featured a First Nations artist who used Native American performative rituals as the basis for his work. Each was applauded more than the last — except in the case of Germany.

In the German pavilion, there is an artwork called “Light to the Nations” by Yael Bartana, an Israeli artist living in Berlin. It is an installation of a Sixties-style model spaceship, suspended at the top of a dark room, floating like a distant solar system in a mist of mesmerising light patterns. The title refers to the Book of Isaiah, when God tells the prophet that Israel’s outward mission will be led by the principle of light. It is about the future of the Jewish civilisation assuming the worst has already happened, posing the haunting question: where would Jews live if they were unwelcome everywhere on Earth?

This was my favourite artwork of the whole Biennale; and, one night, over proseccos in Dorsoduro, I confessed as much to the Emerati pavilion gallerina. I watched as the blood rushed to her face: “That kind of artist shouldn’t have a platform,” she replied. “With everything that’s going on right now, how could any country promote an artist like her?”

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised by her response. Since October 7, art galleries across the West have faced criticism for spotlighting Israeli artists. And since the Biennale opened in April, there have also been anti-Israel protests outside not only the already-closed Israeli pavilion, but also the German one.

What was peculiarly ironic in Venice, however, was that under the logic of identity politics favoured by the Biennale, Germany’s decision to spotlight a Jewish artist was entirely fitting. Isn’t the whole premise of this ideology to shift “the culture” away from those who have “held the power” historically? Why is a German attempt at cultural reparations to the Jewish people not valid, when most other pavilions were essentially a cultural apology to their oppressed peoples?

The answer, I suspect, lies at the start of almost every artist’s career — at art school. Even before October 7, the popularity of the BDS movement in universities, particularly among the coolest art students, was obvious. After October 7, however, more overt anti-Jewish sentiment became firmly embedded in the universities, falling in line with the trends of wider society.

At art school, this is even more pronounced because, on an educational level, the bare minimum is expected from you. I remember from my time applying to art schools how difficult it was to find a course that taught electives in both academic and practical subjects. I was lucky to find a course which doubled as a history of art degree, as one of the only things I was taught on the art side was “artistic research”. Here, lecturers told us that, as artists, walking around a park is as valuable as reading a book. More than anything, they prized transgression for transgression’s sake. Yet transgression has its limits.

For Ben, an Israeli artist and student at a London art school for the past year, the repercussions of this became all too apparent following October 7. Having lost a close friend at the Nova music festival, and one of the only Israelis in the school, Ben (not his real name) felt it his duty to have a conversation with a fellow student about the anti-Israel banners she was hanging around the university, including ones that depicted the state of Israel eliminated from a map of the Middle East and which called for an “end to our university’s research, commercial and institutional partnerships with the ‘Israeli State’”. Concerned by their presence on campus, Ben sent her a polite message, hoping to open up a channel of communication. The activist declined. Ben didn’t push, and assumed that was that.

A few weeks later, however, Ben was summoned by the university. He was told that the activist had filed an official complaint against him for bullying, and was instructed to attend a meeting about his “harassing” behaviour. He was also warned that its outcome could affect his ability to graduate. Eventually, the claim was dismissed, though the university still issued Ben with an “official warning”: if he ever contradicted the student again, his time at the institution would immediately be terminated. Luckily for him, it was his last month before graduation, and he obviously has no plan to return for more.

Ben’s experience is far from unique. Noa, a London-based artist who is exhibiting at Frieze for the first time this year, is also Israeli. A few months ago, a British friend she used to be close to told Noa (also a pseudonym) the reason she’d has stopped talking to her. “I was worried you might be a Zionist,” she said. Her evidence, she explained, consisted of the fact that Noa followed a Jewish art collector and actress Amy Schumer on Instagram — both of whom had posted about the Israeli hostages. Of course, this is something that works both ways. I felt a deep sense of betrayal too when artistic colleagues of many years, in the wake of October 7, started posting about the need for “Palestinian resistance”, or shared a conspiratorial infographic about the impossibility of being antisemitic because “Jews aren’t semites”.

In an industry where being trendy is the most precious commodity, galleries have been equally nervous about taking on Jewish artists. “It’s a big risk for any gallery to take on a Jewish artist right now,” says Sarah, a Jewish artist with gallery representation in London and also speaking to UnHerd anonymously. “As fucked up as it is to say, I feel lucky. It could be much worse.”

Even with Sarah, her Jewishness was a cause for concern. When she joined the gallery, she was asked if she planned “on becoming an online activist”, despite the fact that another artist on their roster is an active pro-Palestine protestor online. At one point during her induction to the gallery, she was told: “We’re going to downplay the fact that you are Jewish.”

In such a climate, it’s perhaps not surprising that many Jews in the arts feel the need to hide their identity. It is striking, after all, that everyone I spoke to for this article insisted on remaining anonymous; all of them fearing the negative impact that speaking freely might have on their careers. One artist told me: “I would love to be open and use my name for your piece, but I can’t risk being dropped by my gallery.”

For some, like Maya, an emerging curator, seeing this has not only been heart-breaking but also discouraging. The pseudonymous artist decided to leave London and move back to Israel. “I miss my friends and family a lot,” she told me. She’d found it exhausting to deal with the relentless anti-Jewish sentiment during her MA in London over the past year.

I understand this. October 7 marked a change in my life, too: I was no longer able to live in a world with so many painful barriers in front of me, so I took several months out, returned home to Madrid, and focused on building myself in other ways. After overhearing artists in my studio talk about how the “Jews control the media”, I wanted to make sure I had skills beyond the art world. I needed to be prepared, just in case, like countless other Jews this past year and throughout history, I am forced to pack up and leave.

There is a broader tragedy here, too. Art dies when there is only one right way to understand and react to the world. It comes alive, however, when it touches on something we can’t quite understand, or something which remains unspeakable. And so, I am reminded once more of Bartana’s work. Standing in that dark room with pounding techno reverberating through the walls and inside my chest, with the plumes of gaseous CO2 unfurling onto the floor, I craned my head towards the light.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe