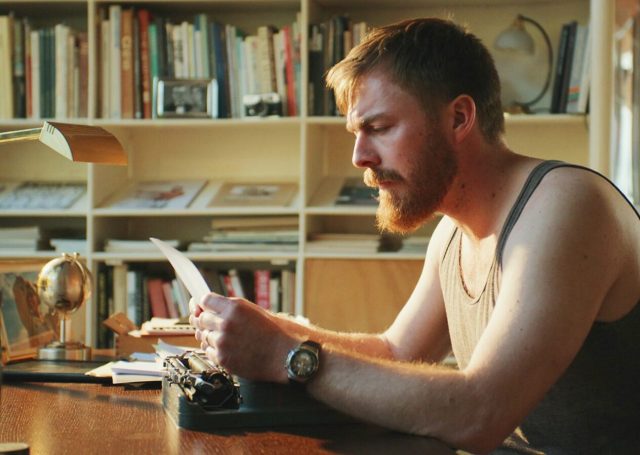

The Last Screenwriter was boycotted for using AI (The Last Screenwriter)

“This machine can produce a 5,000-word story, all typed and ready for despatch, in 30 seconds. How can the writers compete with that?” So asks Roald Dahl in his short story The Great Automatic Grammatizator, published in 1953.

The eponymous machine learns from existing works and can write entire novels in response to manual prompts. By pressing buttons and pulling stops similar to that of an organ, the machine’s inventors “pre-select literally any type of plot and any style of writing”. They choose between “historical, satirical, philosophical, political, romantic, erotic, humorous, or straight” categories, then between themes such as childhood, civil war, or country life, and finally between literary styles such as “classical, whimsical, racy”,or specific authors such as Hemingway, Faulkner and Joyce. Within a year, half of new writing is generated by the machine. The ending of Dahl’s tale is harrowing.

More than half a century later, the fear felt by some writers, artists, and musicians, when faced with generative artificial intelligence such as ChatGPT, is not unfounded or foolish. Those who dismiss it as posing no threat to the creative industries, on the grounds that it can never be good enough, are the deluded ones; AI is more than capable of producing content comparable to that created directly by humans.

Contrary to popular opinion, however, this is not intrinsically dangerous. Rather, the danger is us — or, more specifically, our refusal to engage with it seriously. The current state of AI in the film industry, and the varied reactions to it, exemplifies this. Already, generative AI’s role in film ranges from writing scripts to creating visual imagery, and its adoption has sparked a range of reactions including celebration and anger. Few and far between are those who say simply and rationally: it’s here, so let’s see what it can do, and let’s talk about it, because in doing so, we can shape our creative future.

In this camp sits Swiss director and producer Peter Luisi. When ChatGPT 4.0 was released, Luisi wondered whether it could write an entire feature film. He set about finding out, ensuring his input was that of a typical director, and was not enough to grant him a writing credit. ChatGPT 4.0 was given the initial prompt to “write a plot to a feature-length film where a screenwriter realises he is less good than artificial intelligence in writing”, and asked to generate each scene in turn. Screenshots of the prompting process are available on the project’s website along with the film itself: The Last Screenwriter.

London’s Prince Charles Cinema was hired for the premiere in June, and in keeping with the aim of stimulating discussion, the team made tickets publicly available (although the film is not-for-profit, they decided to charge admission to discourage no-shows) and agreed to pay for promotion. But when posts went up on the cinema’s Twitter and Instagram, there was a furore; many were angry that the cinema was apparently supporting the use of AI in film. The Prince Charles cancelled the screening, citing “the strong concern held by many of our audience on the use of AI in place of a writer”.

When I spoke to Luisi the next day, he was sanguine — “We were sort of hoping that this discussion would happen, we were just hoping it would happen inside the cinema” — and invited me to the relocated premiere. Sitting there felt utterly surreal, a new page in a history book. How good ChatGPT’s screenplay was didn’t seem to matter: what was significant was that we were watching the first film written by a machine. This was just the start.

Kevin Maher, writing in The Times, missed the point when he called The Last Screenwriter a “dud” that should “allay fears” about AI’s threat to the arts. In arguing that the film is sufficiently bad for the Prince Charles protestors to safely “stow those pitchforks”, Maher presents the now tiresome line that AI content is intrinsically worse than human content.

None of which is to say that the writing quality wasn’t worthy of discussion; much of the conversation afterwards centred on the screenplay’s flaws, and how challenging the film had been to direct and act in as a result. (It was novel to join the director of a film in criticising its writer.) One glaring issue is ChatGPT’s penchant for a cheesy phrase, but whose fault is that?

Lead actress Bonnie Milnes was deeply frustrated by the online reaction and the premiere cancellation. She describes The Last Screenwriter as “an exposé of the biases of AI that, if ignored, could have catastrophic consequences for the future of the arts”, and argues that the people who most need to see the film are the ones boycotting it. Watching the film, the challenge Milnes faced in creating any depth of character is palpable; her character had no personality beyond being a wife and mother and much of her very skilled performance was limited to facial expressions.

Meanwhile, away from the glare of mainstream critics, large corporations do what they want. Netflix’s recent three-part documentary on Ashley Madison, the US dating site for people seeking affairs, which faced a huge data breach scandal in 2015, used a number of poor quality AI-generated images, and nobody batted an eyelid. The series is lazy in other ways, too; in one re-imagined scene, an iPhone ringing on a hotel bedside table shows the caller as “Home”, but the call is being made through WhatsApp. The phone is using 5G, miraculous for a decade ago. Additionally, footage which illustrates an interview in the first episode — a hand selecting a shirt from a rail, a male figure walking out to a car — is recycled in the third with a different voiceover.

The choice to use AI to illustrate the fake female profiles set up by the Ashley Madison team to entice men to use the site was hardly surprising, but the brazenly unreal imagery was. Pausing the programme during montages of these “profiles”, I was treated to women holding miniature wine glasses, floating limbs, unusual finger counts, and plug sockets from a parallel universe. Is this just life now? AI can “do hands” these days, but that doesn’t mean we’ll bother, apparently.

So if AI imagery is becoming commonplace in film and TV, where does ChatGPT fit in behind the scenes? The resolution of the 2023 Writers’ Guild of America strikes requires companies instructing screenwriters to edit AI-generated content to pay as much as they would if writers were composing the whole screenplay. AI cannot be a writer, according to their rules, so any editor becomes the writer. But this means that some stories have no writers at all, which doesn’t make sense: it’s an obscuring of the truth, a refusal to accept the reality that AI can write, an ongoing suppression of the situation. (ChatGPT itself isn’t keeping quiet about this: at one point in The Last Screenwriter, the lead character, Jack, says wondrously “this AI is like having an entire writers’ room working around the clock”.)

The day the Prince Charles made its announcement, I attended a preview of the short film The Future Can Be Yours at the Clapham Picturehouse. I’d been invited by the director, Simon Ball, at an AI event. Before the showing, producer and co-creator Ieva Ball handed round homemade chocolates, and their toddler roamed around.

That this was a low-budget production wasn’t remotely evident from the eight minutes of film. Most shots look rather like paintings, and the low frame rate and constantly shifting objects and facial expressions suffuse the whole film with a dreamlike quality. At one moment — my favourite — we suddenly see the actors as they really are, walking down a London street. AI — in this case, a locally run version of the image generator Stable Diffusion — not only enabled the film to be made with a low budget, but induced effects that simply wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. When used thoughtfully and imaginatively, AI can both enhance the artistic process and raise up small, independent projects.

After the screening, I spoke to Leo Crane, fresh from launching the inaugural AI Film Academy Awards in Lisbon. Fizzing with energy, he described the effect of AI on film as a “new wave”, with AI “revealing something that’s almost risk-free. It’s so experimental, you don’t need big budgets, you don’t need experience in filmmaking.” Of course, for scared creatives and their supporters, the idea of those without experience and training being able to make films is precisely where the threat lies, but I found Crane’s optimistic alternative perspective to be irresistible:

“I’ve been in the art world for 25 years, seen a lot of stuff, and some of this is unlike anything I’ve seen before. It’s like a new language. It’s coming from all corners of the world and it’s coming from people who might otherwise be excluded from the film industry. The fact that this is not polished and it’s not perfect makes it more human, even though it’s AI, and that kind of battle between humanity and the machine just reveals that depth of what it means to be human, especially when it breaks down.”

This idea of a creative renaissance, and one which involves people who might not otherwise be expressing their creativity at all, reflects what I hoped would emerge from AI image generators when I first started using them in July 2022. For six months I messed around with Midjourney, making images that made me happy; it didn’t matter that other people didn’t quite “get” them. When I decided to explore what other people were generating, my bubble burst: horrific and illegal content, namely images of children being sexually abused, was the answer. After working with The Times and then the BBC to investigate and expose this, I never regained my initial optimism — until now.

Creativity is not a zero-sum game. There is no limit to how many of us can be creative, no cap on how much art can be enjoyed. Crane’s words capture the inherent artistic possibilities of generative AI, which, unlike us, has no creative inhibitions. It can open up new avenues for anyone who wants to explore, and the more people that do so, the better. Ultimately, it is possible and necessary to simultaneously celebrate creative work like The Future Can Be Yours, analyse projects like The Last Screenwriter, and castigate shoddy AI use like that in Ashley Madison: Sex, Lies & Scandal.

And if we are living in a dystopia, Dahl’s story brought to life, as some people seem to believe, we should at least be speaking about it. For the alternative doesn’t benefit anyone: by instilling a culture of shame, stigma and silence, its critics are working to bring about the very scenario they fear.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe