“We had nowt, but we were happy” became my grandmother’s catchphrase in her later years. I was never sure if she was being serious, not least because I knew how grim the Depression had been in the pit villages of the North East: a time when she’d lost her teenage sister to diabetes and seen two of her closest childhood friends turfed out of their colliery-owned house after their father was killed in an accident at the pit.

But rather than dwell on such hardships, my grandmother grew nostalgic for the everyday kindnesses and instinctive mutuality that, for all their faults, characterised coalfield communities. The extent to which ordinary people relied on one another then is hard for later generations to imagine.

Some of the best evocations of that world can be found in “Kith and Kinship: Norman Cornish and L.S. Lowry”, an exhibition which has recently opened at the Bowes Museum in County Durham. The museum itself is an astonishing sight: a vast Second Empire chateau built on the edge of Barnard Castle by John Bowes, the playboy scion of a local coal-owning dynasty, to house his art collection. Nikolaus Pevsner called it “gloriously inappropriate”. So it is pleasing to see the working-class paintings of Cornish and Lowry take their place alongside all those Raphaels and Van Dycks.

What is immediately apparent on entering the exhibition is the contrasting personalities of the two artists. Cornish, a former miner, was an active participant in the coal town of Spennymoor that remained his constant muse, while Lowry, a rent collector, was the eternal outsider. This is reflected too in their work, where the beaten-down stickmen and women of Lowry’s Salford diverge from the warmth and joviality of Cornish’s Durham folk, a people that he always refused to portray as “cowed and defeated”.

The peasant-strength of Cornish’s subjects call to mind the works of Brueghel, Rembrandt and van Gogh, which Cornish had spent every spare moment studying as a young miner. Yet it was not just his phenomenal talent as a painter that won Cornish so many admirers, but his vision as a storyteller. “He is a painter of place in a way that Thomas Hardy is a writer of place,” wrote Melvyn Bragg. “Spennymoor is the grain of sand in which he brings a whole world to life.”

Lowry, by contrast, has a colder eye. His silent, almost robotic figures seem isolated from one another. “All these people in my pictures, they are all alone you know,” he once said. “Crowds are the most lonely thing of all. Everyone is a stranger to everyone else.” There is a hint in his Salford pictures of Karl Marx’s idea of the alienation of labour. As Robert McManners and Gillian Wales observe in The Quintessential Cornish, Lowry’s characters “are relegated to automata by the harshness of industrialisation and each figure is almost incidental. Norman’s, by contrast, are elevated to centre-stage… They are people who each have a life before, during and after the picture.”

One explanation for this artistic divergence is the type of industrial work that dominated Lowry’s Cottonopolis compared to Cornish’s Durham coalfield. Friedrich Engels once wrote of the “nameless misery” of the workers he observed in Manchester, and novelists from Charlies Dickens onwards described in horror its stygian gloom and satanic mills. But the coalfields were different; here was a landscape that was by no means picturesquely rural, but it wasn’t quite grimly urban either. The miners here had a strange love-hate relationship with the pits too, where the work could be debilitating and often lethally dangerous, but it could also be satisfying and often thrilling. My own pitman grandfather would recount stories about intense workplace camaraderie until the day he died.

The miners also created a distinctive culture, where an interest in the arts was not uncommon — just consider the Pitmen Painters, or even Billy Elliot. Cornish himself once said: “I’m sick of being looked at like some sort of zoo animal or specimen… It assumes that a man who works in a mine is not up to writing or painting or playing music. But it simply isn’t true.” Of course, not every miner was an autodidact. But Cornish’s attitude was certainly shared by my own grandfather, who read voraciously and always had a sketchbook to hand.

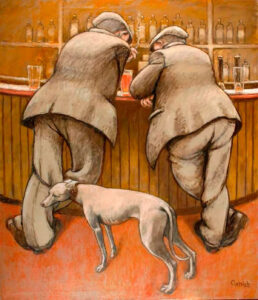

Another hallmark of the coalfields was the working men’s clubs, and Cornish was a fabulous painter of bar scenes. Among my favourites in the exhibition is his much-reproduced image of two flat-cap-wearing blokes leaning on the bar, greyhound at their feet. These men are “Tosser” Angus and Joe Hughes, miners who served in the Second World War in the Durham Light Infantry, and who were among the last men off the Dunkirk beaches, before seeing brutal combat in North Africa and Sicily.

In Cornish’s vision, the worlds of work and recreation are strictly gendered. No women appear at the coalface, where they had been forbidden from working since the 1840s, and the bar room was a male preserve. (Indeed, I saw women being ushered out of the bar of working men’s clubs as recently as the Nineties.) Miners could be as superstitious as sailors in their attitude to women, and it was considered unlucky to pass a female on the way to the pit.

This gendered division of labour was driven by the needs of the coal industry, which needed their thoroughbreds well-cared for, fed and washed around the clock. In many ways, the role of pitman’s wife was similar to that of a groom to a horse. It was common for miners to pay tribute to female labour in their writing and their art, and Cornish’s tender paintings of his wife Sarah performing tasks which might be seen as drudgery — peeling potatoes, cooking, ironing — are both reverent and dignified.

But for all their stoicism there is something wistful about these women. Perhaps Sarah Cornish — an accomplished pianist who had worked as a nurse during the war — nurtured a sense of thwarted ambition that I sometimes detected in my own grandmother. For feminist writers such as Beatrix Campbell, this was a source of shame. “No group of men has been so cold and confident in its exclusion of women, yet so dependent on their support,” she wrote of the miners of the Northern Coalfield. We don’t know if Cornish would have agreed, but a characterful, almost Rembrandtian, sketch of his grandmother, which he drew when he was only 17, says something profound about the respect he felt for the matriarchs that made these communities tick.

I am sure that many of the visitors to this exhibition will feel the pangs of nostalgia. Yet this was far from a progressive age. For the strength of community in these pit villages, and their distinctive work ethic, relied on socially-enforced codes of behaviour, and a low-level surveillance culture that our modern individualistic sensibilities would probably make us recoil from today.

And yet, in a recent interview, the political philosopher John Gray argued that much was lost when his tight-knit, “rather matriarchal” street community in the coal and shipbuilding town of South Shields was broken up. When the Gray family and their neighbours were moved out of town in the Sixties to better housing in newly-built orbital council estates, he noticed that almost immediately “there was graffiti, there was street crime, there were all the pathologies of what sociologists call anomic individualism”. He concluded that “great advances”, such as those brought about by the Labour government of 1945-1950, “are often associated with losses”. These formative early years led, he said, to a lifelong scepticism about progress.

How, then, might we assess the progress of the North of England since the days of Lowry and Cornish? The North East in particular has had a difficult last century, with only sporadic interludes of confidence and prosperity — notably in the Fifties. It now has among the very worst health, education and employment outcomes in the country. Indeed, for all the improvements in housing and healthcare, the coming of the centralised welfare state in places such as County Durham was a mixed blessing, emasculating once-proud local institutions, and bureaucratising many aspects of social life.

There are still occasional glimmers of the old days. In “left behind” Sacriston, a former pit village not far from Spennymoor, local women took over the derelict former Co-op in 2019 to establish a family centre, and local networks were set up to tackle male loneliness. These community efforts, according to a team of UCL researchers, were galvanised by a sense of “constructive nostalgia” for a time when the village was confident enough to solve its own problems through a web of communal institutions:

“But people in Sacriston are not nostalgic for mining disasters, unemployment, emphysema or dysentery. Rather, they lament a lost era of relative prosperity based on secure local employment and the erosion of the community bonds that were the basis for their struggle to improve life in the village, which produced genuine ‘pride in place’.”

By stirring our collective memory, the Kith and Kinship exhibition reminds us of what community life in the North East was and could be again. The challenge for anyone concerned about the region’s future is not to recreate the past, but to convey its history to inspire a new generation of community builders.

***

Kith and Kinship: Norman Cornish and L.S. Lowry is at the Bowes Museum from 20 July until 19 January.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe